Measles outbreak gets second wind; More Clark County cases likely in coming weeks

Published 9:58 am Tuesday, February 19, 2019

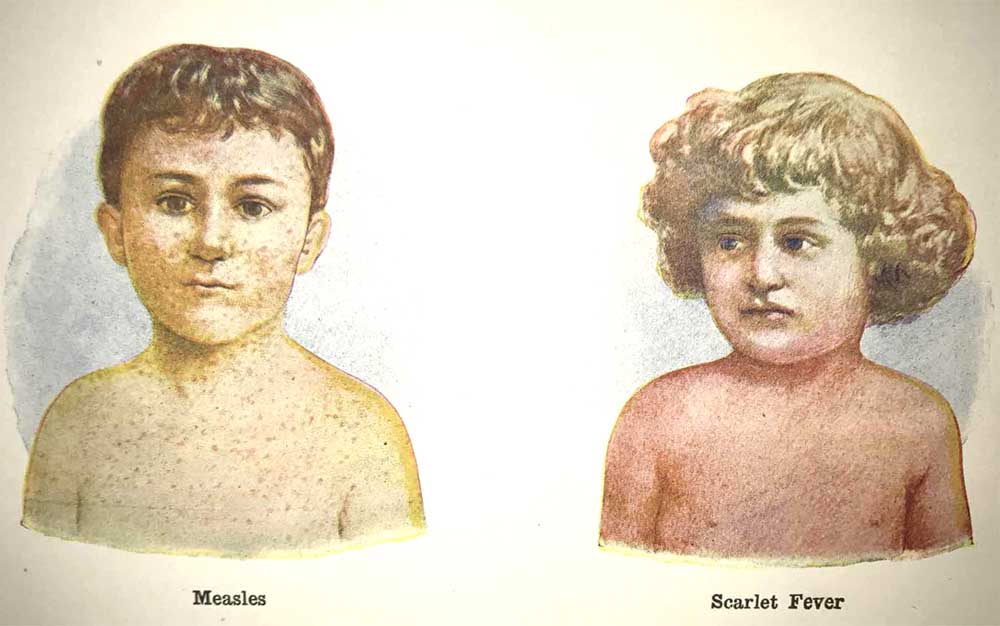

- This color plate from the 1910 book, ‘A Practical Guide to Health,’ illustrated the difference between measles and scarlet fever. The book advises giving children heroin for measles-related pain, and notes that the disease ‘nearly depopulated aboriginal tribes when first introduced by travelers.’

WASHINGTON — With only one new case last week, health authorities in Clark County were cautiously optimistic that efforts to suppress a measles outbreak were working. However, in a Friday, Feb. 15 interview, county Health Officer Dr. Alan Melnick said the drop in cases could also be “the calm between two storms.” The latter turned out to be true.

The second wave

On Saturday, six new cases popped up. By Monday afternoon, the county had confirmed two more cases and identified four new exposure sights. Now, numerous new cases are likely in the coming weeks.

According to Melnick, measles is “exquisitely contagious.” Unvaccinated people who come into contact with it have about a 90 percent chance of getting sick. The incubation period — the time between exposure and the appearance of symptoms — can last up to three weeks. The initial symptoms can seem like a regular flu or cold, and infected people are contagious for four days before the distinctive head-to-toe rash shows up and four days after. As a result, measles sufferers often infect others before realizing they’ve got the virus.

“You see generations of cases. You have one cases that exposes a bunch of people. Seven to 21 days later, they get sick. They expose another generation,” Melnick explained.

New exposure sites

Since the beginning of the year, there have been 62 cases in Clark County, as of Feb. 18. There has been one case in King County, and a handful of cases in Oregon. There have also been outbreaks in a few other states, including more than 200 cases in insular orthodox Jewish communities in New York.

Because of Pacific County’s proximity to Clark County — about two hours away by highway — and routine travel between the two for things like clam seasons and doctors appointments, it remains a possibility that measles may spread to the coast.

The new exposures occurred in a clinic, two campuses in the Evergreen Public Schools district and a Fred Meyer in Battle Ground. Of particular concern are the exposures at Image Elementary School and Pacific Middle School, both located on the outskirts of Vancouver. In both cases, the infected children went to school for several days during their likely contagious periods, so there is a strong chance other unvaccinated children were exposed. Those cases could start showing up any time between now and early March.

Health authorities can’t catch all the cases. Some people never go to the doctor, so their cases don’t get reported.

“There are cases that will never come to anybody’s attention,” Melnick said.

Campus contagion

In a Feb. 18 email, Evergreen Schools Spokeswoman Gail Spolar said the district has made a concerted effort to get parents to vaccinate over the last few weeks. In mid-January, 7.7 percent of students in the district were not protected from measles. Now, only about 3.3 percent remain unprotected. That works out to 218 susceptible students across the district’s 37 campuses.

The district has excluded all unvaccinated children and staff. They could be absent for up to 21 days, Melnick said.

There are likely many other unprotected children in the area, including some who go to private schools and home schools, and those who are too young to receive the vaccine. Children outside of public school systems tend to be vaccinated at lower rates, Melnick said.

‘Not judgmental or blaming’

Washington has a large number of parents who have fallen prey to myths about vaccination. Reasons for opposition include fears that vaccines contain poisons or cells from aborted fetuses, a mistaken belief that vaccinated children “shed” disease, and propaganda spread by a former doctor who lost his medical license after publishing a fraudulent 1998 study that said the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine causes autism.

Melnick said the county tries to educated reluctant parents without shaming or criticizing them.

“I think we need to get the appropriate info out. I think blaming people is gonna drive folks away from getting immunizations for their kids,” Melnick said. “We need an approach that is not judgmental or blaming.”

Active monitoring

So-called “vaccine hesitancy” has created an enormous workload for local and state public authorities. When new cases are reported, health workers contact the families and try to identify anyone who might be especially vulnerable, including immunosuppressed people and pregnant women. They try to get those people immune globulin, which can be effective for up to six days after exposure.

The health workers conduct in-depth interviews to learn everywhere the infected people went during the contagious period. If the patients visited populous places like airports and grocery stores, authorities notify the public. The affected families are placed on active monitoring, meaning that health workers call them every day to make sure they’re staying at home and find out what stage the disease is at and whether anyone else in the household has fallen sick. At one point, Clark County was actively monitoring almost 200 people.

‘We’re stretched pretty thin.’

For the last several weeks, almost half of Clark County Public Health’s staff have been dedicated to measles suppression. Additionally, workers from the federal Centers for Disease Control and from other regional health departments have traveled to Clark County to help out. Many workers were pulled off of other important public health projects to focus on measles.

“We’re stretched pretty thin,” Melnick said.

So far, the county has spent over $400,000. Together, the county and state Department of Health have spent about $1 million on efforts to suppress the disease.

Melnick said it’s not uncommon for measles outbreaks to last through two or three generations of cases. That means it could be weeks or even months before the virus goes away.

“I’ll start feeling extremely optimistic when we go a full incubation period without a case — 21 days,” Melnick said. “I think I’ll be able to say this outbreak is over when we go two incubation periods.”