This Nest of Dangers: 1941 and a world war — Vaslav Vorovsky delivered lard to our beach

Published 2:23 pm Tuesday, March 18, 2025

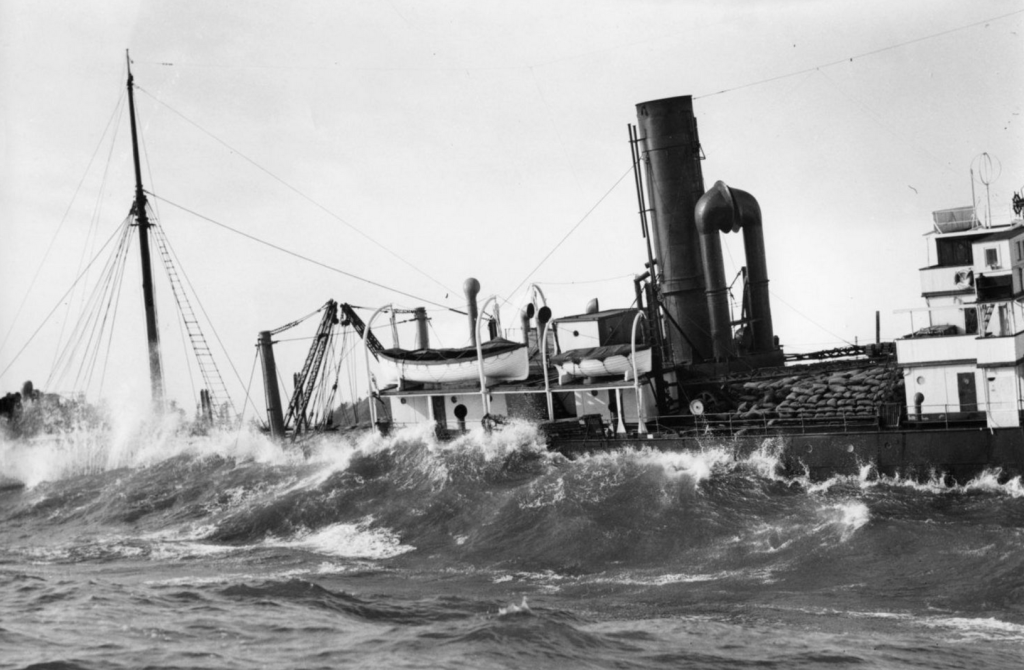

- The Vaslav Vorovsky lists as it is overcome by surf after grounding on Peacock Spit in 1941. The entire ship was lost, but its cargo was salvaged by local people as it washed ashore. This included a vast quantity of cooking lard, which longtime Long Beach Peninsula residents still recall being used in pie crusts throughout the lean years of World War II.

Two notable shipwrecks bracketed 1941 at the mouth of the Columbia River. The first involved a Russian ship taking war supplies home to their Fatherland.

“Much of the material now going to Russia, via Vladivostok, moves through the ports of the Pacific: Columbia River, Puget Sound, San Francisco,” reported the Medford (Ore.) Mail Tribune in February.

“For the first time in five years American cotton moved to Russia in large amounts, and oil drilling machinery was shipped in mass movements during the first 11 months of 1940, according to a Commerce Department report.

“In those 11 months Russia took $80 million in war material from the United States. This year the amount will be greater, unless licenses are applied.”

Afoul of the spit

Early in April 1941, a Russian steamer loaded with such war materiel ran afoul of the spit north of the Columbia River’s entrance.

“The stranded Russian steamer Vaslav Vorovsky, caught in the treacherous sands of Peacock Spit … was cracking in three places today. The Cape Disappointment lookout reported that an eight-foot crack had appeared in the hull of the ship aft of the bridge, and that another big split showed fore of the bridge.

“A hundred or more casks and barrels littered the beach near the wrecked ship as the cargo floated away.

“Valuable oil pumping machinery, which the Vorovsky was hauling to Vladivostok, is a total loss, as the ship’s engines are dead and the water is not deep enough to support a winch-carrying boat of sufficient size to lift the machinery.

“Captain J. Tokareff, who waited until all of his crew were taken ashore, was rescued today by the Coast Guard. He was taken off by a surf boat from the Cape Disappointment station while the 2,677-ton freighter ground itself to pieces in the sands.

“The captain suffered severe leg injuries when a sudden swell tossed the surfboat into him as he came down the side of a Jacob’s ladder. He was taken to Ilwaco for treatment.

“For nearly 24 hours Captain Tokareff had stuck to his ship alone, clinging to the rolling bridge after his crew had been taken off. Last night he flashed ‘boat’ on his signal lamp.

“The 55 members of his crew, including two women, shabbily dressed, huddled dejectedly in Cape [Disappointment] life station. They told how the ship had put out to sea early yesterday on its way back to Vladivostok and ran into a 40-mile wind. The ship turned back toward port but was caught by a tide and the steering gear developed trouble. Their anchors failed to hold and the ship was smashed broadside against the sand bar of Peacock Spit, ‘graveyard of ships,’ southeast of Cape Disappointment.

“Captain J. Tokareff, who speaks no English, refused to go with his crew. ‘He shouted in Russian and we shouted in English,’ said a Guardsman, ‘but he refused to budge.’

“High winds and heavy seas were grinding [the Vorovsky] to pieces on the sand spit and great holes had been torn in the bottom,” the Everett (Wash.) Daily Herald reported.

Tugs to no avail

On April 4, 1941, the Chinook Observer wrote of the wreck:

“Once again Peacock Spit takes her toll in the line of navigation, when on Wednesday night about 11:55 p.m. the 365-foot Russian freighter Vazlav Vorovsky with a damaged steering apparatus, went aground on the treacherous spit between Jetty A and Cape Disappointment. …

“Two tugs, the Kithian and Arthur Foss, both of Tillamook, were standing by to make a try at pulling the vessel off at high water, about 6:11 p.m. Thursday, but Coast Guardsmen had little hopes of seeing the ship freed. …

“According to Portland newspapers, the freighter left Portland with 3,476 long tons, consisting of machinery, wool rags, and lard.”

Roaring sou’wester

The next day, Associated Press reports from Astoria described the situation:

“Astoria, Ore., April 5 — Her bridge carried away and masts, booms, and cargo smashed together like match sticks, the Russian freighter Vazlav Vorovsky was a complete wreck today. The steamer … was jammed deeper into the sands of inner Peacock Spit by a roaring sou’wester last night.

“Heavy seas continued to batter at the hull, which had split into three sections, and promised to sink the whole ship beneath the water surface.

“Light cargo washed free through bulkplate seams and littered the beach, but most of the $1,250,000 cargo of heavy machinery and tools apparently could not be recovered. … John McCormick, chief boatswain’s mate of the Point Adams Coast Guard Station, said 16 of the 42 mail bags aboard the Vorovsky had been recovered,” according to the Medford Mail Tribune.

Salvagers arrive

As always, when there was a shipwreck, locals rushed the beach seeking what they might find. As the threat of war-time rationing loomed, the bounty brought by the tide was most welcome. As with seabirds, particularly gulls, salvagers had conflicts, which made for interesting news stories:

“Astoria, Ore., April 8 — What beachcombers consider their own unwritten law — thou shalt not hijack — is being violated all over the place since the cargo of the wrecked freighter Vaslav Vorovsky began washing ashore.

“There was the case of a Salem, Ore., soldier at nearby Fort Canby. He drove his car along the railroad trestle from the Fort to the end of the Jetty on Sand Island picking up a carload of 56-pound-boxes of lard. There was no turn-around, he retraced his route in reverse gear.

“At the fort he was promptly slapped into the guardhouse for driving on the trestle, and while he was on the inside somebody hijacked his lard and peddled it for $1 a case in Ilwaco. The lard, incidentally, has proved a bonanza to the soldiers. A party of them financed a trip home to Medford with a load of it,” according to the Capital Journal (Salem, Ore.).

40,000 cases

“Forty thousand cases of pure lard floating from the hold of the cracked up Russian vessel Vaslav Vorovsky put a very smooth and shiny finish on beachcombing at Peacock Spit and Long Beach Peninsula, thousands of cases changing hands from $1 to $3.50 per 56-pound-case, until Russian representatives protested to Lloyds of England who have the insurance on the cargo and who, in turn, sent their representative Frank Sweet from Portland to put a stop to the land office business going on here.

“One soap company buyer from Tillamook, Or., had purchased many hundreds of cases of the lard at $1 a throw.

“Ralph Smith, Ernest Jacobson Jr., and Wayne O’Neil, all of Long Beach, were the only persons on the beach last Friday morning about 7:30 o’clock and at around 8 a.m. the boys witnessed the hull give way to free a great cargo of lard. They had 50 cases of the grease piled up before anyone else arrived. But lo and behold, the lads had no way to get the stuff to market and by that time fishermen had smelled the lard and were coming, with no boat to rent, lease or steal.

“So on with the march of salvaging lard, until Sweet arrived here Tuesday and had Sheriff Peter Maloney and his deputies call a halt on all deals. So the big lard business is all off for the present and Deputies Lark Whealdon and Sol Mechals, both of Ilwaco, are patrolling the beach at Peacock Spit day and night to see that no lard slips away,” the Chinook Observer reported.

Official inquiries

The Medford Mail Tribune of April 9, and the Bremerton Daily News of April 10, made note of the official inquiries into the case:

“Portland, Ore., April 9 — Capt. George Conway, Columbia River Bar pilot, told the Oregon Pilot Commission yesterday that the faulty steering apparatus and slowness of the Russian crew in understanding his orders caused the grounding of the Russian ship Vazlav Vorovsky last week.”

“Portland, April 10 — The Federal Bureau of Marine Inspection yesterday opened an investigation into the wrecking of the Russian steamer Vazlav Vorovsky. Inspectors questioned Capt. S. Tookareff, who said the steering gear of the vessel … was in working order until after the ship was beached. He gave similar testimony, contradicting a river pilot’s story before the Oregon Pilot Commissions earlier this week.”

Canal idea, once again

Between the shipwrecks of April and December, as the national thinking pivoted to military subjects, U.S. Sen. Richard L. Newberger, D-Oregon, wrote of a proposed infrastructural change involving the Columbia River, Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor. As printed in the Albany Democrat-Herald, his article reads:

“A 64-mile navigation canal connecting the mouth of the Columbia River with the southern tip of Puget Sound? The Rivers and Harbors Committee has just directed the Corps of Army Engineers to review the possibilities of such a project. … Money counts for little these days where considerations of defense are concerned. … An inland waterway … would stretch from Alaska to far up the Snake River in Idaho. …

“On its main section, that between Puget Sound and Grays Harbor, the Chehalis River provides the principal artery. All that men must do is deepen the channel and put in locks …

“The bulk of this amount [$33,921,638] would be spent on the stretch connecting Grays Harbor with Olympia, for here 12 locks would be required with a total lift of 90 feet. This would be necessary to get boats back and forth over the passes through the Coast mountain range. …

“Submarines, destroyers, torpedo boats, and other craft would be able to travel inland between the Columbia and the Sound, protected from any enemy force by the shore batteries at Fort Stevens, Fort Columbia, and other strategic military posts. …

“Two recent developments … add to the stature of the canal as a national defense enterprise. One is the immense expansion of the Bremerton Navy yards at Puget Sound. … The other development is the construction of two huge aluminum plants along the Columbia River. Material from these plants could be transported speedily and cheaply by water to the vast Boeing aircraft factory in Seattle.”

On war footing

On Dec. 7, 1941, the nation of Japan sent bombers along the mountains of Oahu to bomb the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. Life at the mouth of the Columbia River changed abruptly.

“Columbia River defenses were ordered to fire on ‘any enemy ship on sight,’ and Tongue Point Naval Air Station and the Coast Guard maintained a vigilant watch on the coast. Sheriff Paul Kearney of Clatsop County posted guards at all strategic points in the Columbia’s entrance,” reported Salem’s the Capital Journal of Dec. 8, 1941.

Wreck of the Mauna Ala

Three days later, Dec. 11, the Everett Daily Herald wrote of the shipwreck of “the [480-foot] Matson Navigation Company freighter Mauna Ala, [which] was hard aground in a light surf three miles south of the Columbia River Bar. … Experienced observers ashore said there appeared to be no chance of freeing her.

“Coast Guardsmen were unable to explain her grounding, which occurred at 6 o’clock last night in a light fog which did not greatly reduce visibility. Shore observers said they could see her coming in and that she was within sound of the surf before she struck.

“Coast Guardsmen would not comment, but watchers on shore said at least one cutter tried unsuccessfully to free the beached boat last night. At low tide this morning she was less than 700 yards offshore and listing heavily to port. It could not be determined from shore whether her plates were buckling.

“Witnesses said they believed the Mauna Ala tried to grope her way into the Columbia despite orders forbidding entrances at night.

“All navigation lights, including those of lighthouses, were extinguished with the start of war.

“She had no bar pilot aboard.

“One shore watcher said, ‘It looked like her helmsman took a stab for the river in the dark and missed by three miles.’

“The Mauna Ala is a craft of 6,805 gross tons, … is 420 feet long, and has a 54-foot beam. She was built in 1918 at Bath, Me.”

Breaking up

In another two days, on Dec. 13, the Tacoma News Tribune reported that the ship was breaking up on Clatsop Beach:

“The Mauna Ala had sailed for the Islands and was 750 miles at sea when word came of the attack on Pearl Harbor and she was ordered to return. Due to the blackout of both navigation lights at the mouth of the Columbia River and radio beams, the Mauna Ala missed the river entrance and drove in on the sands.

“A moderate swell is reported to have been running and in it the Mauna Ala swung broadside to the beach almost immediately. Heavily loaded, the ship started to break up at once as her bulkheads broke under the pounding from the surf.

“Part of the ship’s cargo was 60,000 Christmas trees loaded on Puget Sound.

“The ship was undoubtedly heavily loaded as the line has been running extra ships to keep up with orders from the Islands which have included not only the usual shipments, but defense orders and supplies for the heavily augmented population due to military construction and occupation.

“Capt. Saunders and all of his crew were safely taken from the wreck. Capt. Saunders is a veteran officer of the Pacific, having grown up at sea. His father commanded sailing ships and took his family with him on his trips.”

Several days on, reports said the ship had broken in two and sunk deep into the sands. Locals estimated that the bow had settled 12 feet.

The final comment about this unfortunate wreck forecast a cheerless Christmas for the Islands. Hawaii’s black-out regulations forbade Christmas lights, and their Christmas trees were strewn the length of a north Oregon beach. It would be a somber Christmas.

Closed at night

One final notice in 1941 about nautical life at the mouth of the Columbia River came from the Chinook Observer:

“Captain W.H. Munter of the U.S. Coast Guard issued the following release to the Observer Monday: ‘Ship control regulations: Effective Monday, Dec. 22, 1941, Columbia River entrance will be closed to traffic between sunset and sunrise. Main channel range lights, Clatsop Spit lighted whistle buoys 10 and 12 will be extinguished.’”