Column: Whales and the quest for human harmony

Published 8:05 am Monday, July 10, 2023

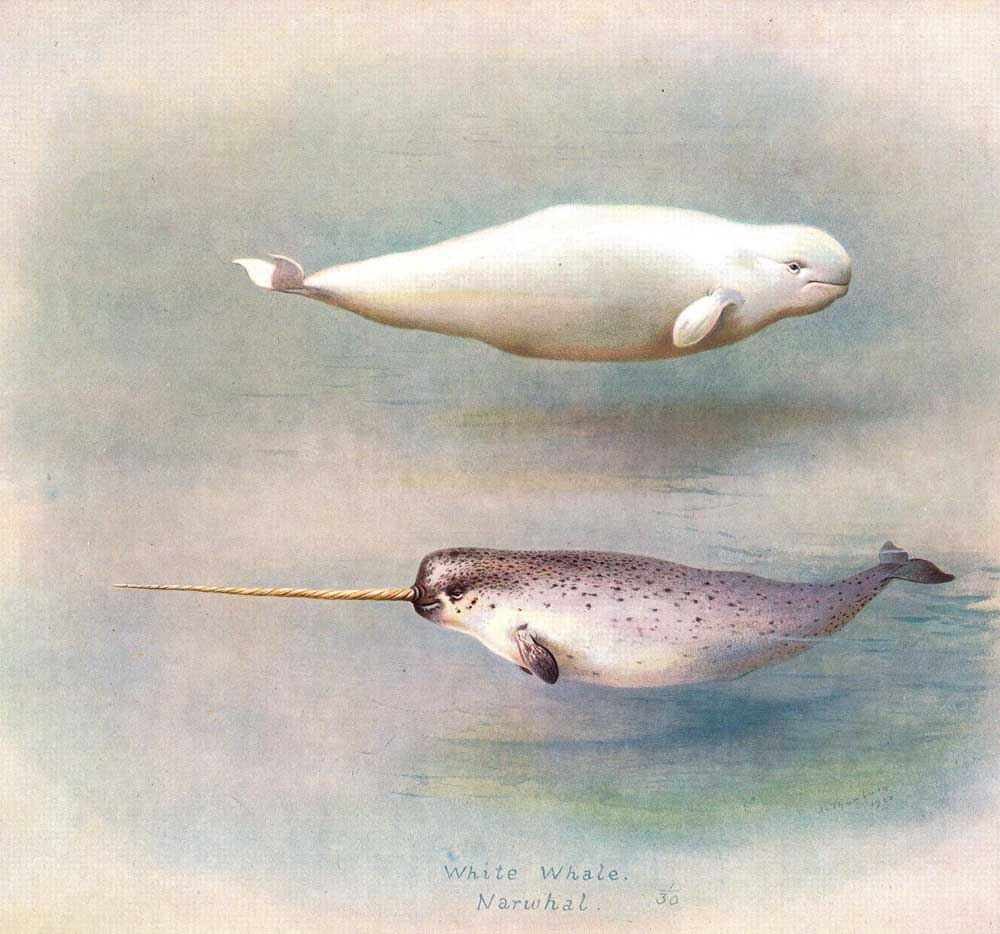

- Illustration of a narwhal (lower image) and a beluga (upper image), its closest related species.

Some columns have their origins in the strangest places. And perhaps this one is a little off the “wahl.”

Trending

In this case, the instigation is a story about a male narwhal that wandered into Canada’s St. Lawrence River and was befriended by a colony of beluga whales. I listened to a reading about it during a communications therapy session for my autistic son, Nicky.

Narwhals are spiral-tusked, 2,000-pound members of the whale family. They’re sometimes called “unicorns of the sea.” They live in Arctic regions and rarely wander as far south as the St. Lawrence River, at least about 700 miles south of their normal territory.

This particular narwhal was first spotted in the St. Lawrence in 2016 and was still around last fall. Biologists say the narwhal — whom they’ve named Nordet — is approaching sexual maturity and showing signs of wanting to mate with the belugas.

Trending

Expecting a narluga?

Such an event would produce an ultra-rare cross-breed that occurred only once before in recorded history: a narluga, according to press accounts.

The challenge is that gene studies show belugas’ and narwhals’ last common ancestor lived about 5 million years ago. The species’ development since then could make communication and sexual reproduction difficult if not impossible.

What is it that makes us suspicious — and often hostile — to people who are different and outside “our tribe,” be it based on politics, ethnicity, religion or class?

The biggest obstacle, though, may be social acceptance. Scientists tracking the whales note that human societies have sociological taboos — such as marrying family members — and the whales may have similar “exclusionary rules.”

“The question becomes: Is the narwhal integrating well enough socially to reproduce?” Robert Michaud, president and scientific director of the Quebec-based Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM), told CBS in 2018. “Who knows if in societies of belugas there is a sentiment of ‘A narwhal? Nope. We shouldn’t do that.’”

Michaud reported that the narwhal is getting along with the belugas well. “It’s like a big social ball of young juveniles that are playing some social, sexual games.”

In October, GREMM reported that “Nordet has managed to integrate among the belugas and is now seen every year among them. Again this fall, Nordet was spotted by our research team!”

Researchers are intrigued by the prospects for breeding and the possibility that climate change could push these two species together.

Why can’t we?

I’m more interested in what it means for humans.

If species separated by 5 million years of evolution can get along, why can’t we? There are minor generic differences among homo sapiens, but the human family is far more closely related genetically than belugas are to narwhals.

A bunch of questions arise. Is the human tendency to distrust outsiders due to genetics, or is it cultural? Or is it both, in that cultural traits can be reinforced by natural selection?

What is it that makes us suspicious — and often hostile — to people who are different and outside “our tribe,” be it based on politics, ethnicity, religion or class?

This all gets into the nature vs. nurture debate. If we are genetically programmed to be hostile, we’ll have a thorny path to achieve world peace and cooperation on a vast range of global troubles. Are we “locked in” to endless conflict within the human family?

The American Society of Human Genetics asserted in 2020 that our genes do not determine our strengths and weaknesses of character. It said: “Humans cannot be divided into biologically distinct subcategories or races, and any efforts to claim the superiority of humans based on any genetic ancestry have no scientific evidence. Moreover, it is inaccurate to claim genetics as the determinative factor in human strengths or outcomes when education, environment, wealth, and health care access are often more potent factors.”

Fine, but this seems to be an oversimplification. Surely, for example, both genes and the environment contribute to the “criminal mind” — in which a person cannot discern — or care about — right from wrong.

Certainly, over several generations, laws, calamities and other changes to our environment and culture must inevitably shape our genes through natural selection. Geneticists do search for the forces that create what might be called “national character.” What, for example, caused Middle Eastern societies apparently to be tribally oriented? Why are the Chinese seemingly more acquiescent toward authority? Why do Ashkenazi Jews generally have higher IQs?

We might assert, too, that Russians’ willingness to accept Putin and totalitarian rule might be due to the immense slaughter and suppression of those who dared oppose the tsars and commissars. Has rebellion been bled from the gene pool?

Certainly, it seems obvious that some of us are born rebellious, some are born quiet and timid, and that we all have wide ranges of talent and intellect.

For centuries, philosophers and other thinkers have debated whether humans are essentially good or bad. In 1651, Thomas Hobbes’ “Leviathan” justified authoritarian rule by asserting that human society tends toward anarchy and that a strong leader or protector is needed to preserve order. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on the other hand, asserted that humans are naturally good and that all men were socially equal.

Not ‘locked in’

Today, I’d gander many of us would consider both Hobbes and Rousseau equally right and equally wrong.

There’s no denying the formative power of our DNA, but most of us reject the idea that we are “locked in” as either good- or evil-doers. Surely, our genes do not totally predetermine our character and life’s path.

Still, we carry eons of genetic baggage with us, and some of it is primitive and violent. Astronomer/philosopher Carl Sagan referred to this as “the reptilian mind,” the early evolutionary part of our brains.

Our struggle to create a peaceful and just society in large part depends on overcoming parts of our genetic heritage. It’s easy in these conflict-ridden days to think we’re on the wrong path. There has always been struggle, chaos and hate in the human family, but we must be optimistic in the power of our intellects to overcome the heritage of our genes.

Nordet and the Belugas are giving me hope that I’m right.