Living with Northwest Wildlife: Washington elk

Published 4:00 pm Tuesday, November 15, 2005

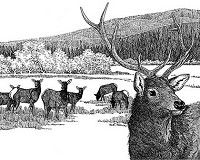

- <I>Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife</I><BR>Figure 2. During the mating season (called the rut) in early fall, the larger, more aggressive bull elk gather harems of cows, which they defend against competing bulls.

Elk range in color from light brown in winter to reddish tan in summer, and have characteristic buffcolored rumps. In winter, a dark brown, shaggy mane hangs from the neck to the chest. Bull elk have large, spreading antlers.

Like other members of the deer family, the antlers of bull elk grow during spring and summer beneath a hairy skin covering known as velvet. In late summer the velvet dries and falls off to reveal the bonelike structure of the fully-grown antlers. Elk shed their antlers beginning in late February for the largest males, extending to late April and even early May for younger ones. New antler growth begins soon after shedding.

Two subspecies of elk are found in Washington.

Roosevelt elk (Cervus elaphus roosevelti, Fig. 1), named after U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, occur in the Coast Range, the Olympic Range, and the west slopes of the Cascades. Olympic National Park in northwest Washington holds the largest number of Roosevelt elk living anywhere (about 5,000). This subspecies is the state mammal of Washington.

Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) occur primarily in the mountain ranges and shrublands east of the Cascades crest. Small herds have been established, or reestablished, throughout other parts of western Washington. Rocky Mountain elk populations currently in Washington stem from elk transplanted from Yellowstone National Park in the early 1900s.

Rocky Mountain elk are slightly lighter in color than Roosevelt elk, and some experts believe they are slightly smaller in size. The antlers of Rocky Mountain elk are typically more slender, have longer tines, and are less palmated than Roosevelt elk antlers.

“Wapiti” is the name for Rocky Mountain elk in the Shawnee language and means “white rump.”

Hybrids, or genetically mixed populations of Roosevelt elk and Rocky Mountain elk, are common in the Cascade Range.

Facts about Washington ElkFood and Feeding Behavior Elk require large amounts of food because of their body size and herding tendencies.

In spring and summer, when food is plentiful, elk are mainly grazers – eating grasses, sedges, and a variety of flowering plants.

In fall, elk increasingly become browsers, feeding on sprouts and branches of shrubs and trees, including conifers as a last resort when snow covers other plants.

During fall and winter, elk continue to eat grasses when these are available and not covered by deep snow.

Like deer and moose, elk are ruminants. They initially chew their food just enough to swallow it. This food is stored in a stomach called the “rumen.” From there, the food is regurgitated, then re-chewed before being swallowed again, entering a second stomach where digestion begins. Then it passes into third and fourth stomachs before finally entering the intestine.

Cover and Range Needs Elk are hardy animals that have few physiological needs for cover. They do, however, use cover during extreme weather, to avoid hunters, or when they are harassed. Cover also conceals newborn calves from predators.

Ideal elk habitat includes productive grasslands, meadows, or clearcuts, interspersed with closed-canopy forests.

Year-round ranges for Rocky Mountain elk vary from 2,500 to 10,000 acres, and usually include distinct summering and wintering areas.

Year-round ranges for Roosevelt elk are smaller, usually 1,500 to 4,000 acres, because they are generally found where the climate is less severe and where food and cover are more readily available.

Social Structure Elk are social animals, living in herds for much of the year. During spring, summer, and winter, elk tend to split into cow-calf herds and bull herds.

Cow-calf herds are usually led by older, experienced cows and may include adolescent bulls.

During the mating season (rut) in early fall, adult and subadult bulls find and temporarily join cow herds. The larger, more aggressive bulls try to gather harems of cows, which they defend against competing bulls (Fig. 2).

Harems range in size from three to four cows to as many as 20 to 25 cows. Bulls socially dominate the cows within their harems, but the movements of these breeding groups are still determined by older, lead cows.

Adolescent males form small bachelor groups or patrol the edge of breeding harems.

Breeding activities cease by mid-October; bulls usually leave the cow-calf groups then and the herds disperse into wintering areas.

Reproduction Mating occurs during the fall rut, and successful bulls breed with numerous females each year.

Once the rut begins, mature bulls challenge each other vocally, emitting high-pitched calliope-like whistles, or “bugles.”

Cows have an eight- to nine-month pregnancy, which results in the birth of a single spotted calf in late May or early June.

The timing of birth seems to optimize calf survival by being late enough that the risk of cold, inclement weather has passed, but early enough so that there is considerable time for calves to grow before the onset of next winter.

Just before giving birth, a cow elk will leave the herd and select a birthing place. Because predators would easily detect large groups of elk, cow elk appear to avoid grouping with other elk until their calves are large enough (usually about two weeks of age) to run effectively to escape predators.

Other cows sometimes tend calves when mothers are feeding; a mother may nurse her calf for up to nine months.

Calves grow quickly and lose their spots by summer’s end. By the onset of winter, a calf that entered the world weighing 35 pounds may tip the scales at 225 to 250 pounds.

Mortality and Longevity With a superb sense of smell, excellent hearing, and a top running speed of 35 mph, elk are well equipped to avoid the few predators capable of bringing them down.

Cougars prey upon adult elk; calves may also fall victim to bears, bobcats, domestic dogs, and coyotes.

Hunting, automobiles, predation, and habitat loss all take their toll on elk populations.

Most elk are physically declining by age 16, and a 20-year-old wild cow elk is very old. Bulls generally do not live as long as cows, rarely surpassing 12 years.

Viewing Elk Elk are primarily crepuscular (active mostly at dawn and dusk), so early morning and late evening are the best times to observe them. But when temperatures soar or when they are harassed, elk may become more active at night.

When disturbance levels are low and temperatures mild, elk may be observed feeding in short bouts throughout the day. When not hunted, elk adapt well to humans and find lawns and golf courses excellent places to graze.

A good time of year to observe elk is in fall. In late September and October, bulls are battling each other over females and are not as concerned about being seen. This is a fascinating time to observe elk because the shrill bugles of the bulls can often be heard near dawn and dusk.

Leafless trees allow greater visibility, and when it is raining there is less chance of being heard crunching through an area. However, be aware of open hunting seasons during this time of year and wear bright orange clothing for your safety. Also, care needs to be taken when around adult male elk during the mating season, particularly in areas where they are accustomed to people, such as national parks.

The best way to view wild elk is to find a meadow, clearcut, or other open grassland elk have been using and to wait quietly nearby. Because elk have a keen sense of smell, it is best to be downwind of where you expect them to come from. (Contact your local Fish and Wildlife office for information on where to view elk in your area.)

Feeding Areas In winter, look for pits dug in snow where elk have been pawing for food, or for the well-worn trails or crisscrossing tracks in the snow typical of foraging elk.

Gnawed aspen and other deciduous tree trunks are also common in elk country during winter. The bottom-teeth-only scrape marks of elk and moose are virtually identical. Gnawings may also be found on downed trees and branches and are easily distinguished from the chisel-like cuttings of beaver.

Aspen trunks that have been gnawed year after year eventually develop a rough, blackened trunk as far up as the animal can reach. A grove of black-trunked aspen is a sign that winter range has been heavily used by elk or moose.

Tracks and Trails Elk, much easier to track than most animals due to their weight, leave marks in or on almost anything they walk over. Tracks, often found in large numbers indicating a passing herd, are easy to identify and follow.

Like all members of the deer family, elk have cloven hooves that normally resemble a split-heart shape on soft earth. The dewclaws on all four feet may register in several inches of mud or snow. Hoof prints may be splayed wide on slippery surfaces, or when the animals were running.

Elk trails are often several animals wide and quite noticeable at the transition from grassland into brush or woodlands.

Droppings Given a steady, consistent diet, pellets deposited by deer and elk may be the same general shape and texture. Individual pellets are usually dimpled at one end and have a small projection at the other, giving them an almost acorn-like shape. However, elk droppings are slightly larger, and whereas an adult deer may leave 20 to 30 pellets at a time, elk may deposit twice that many. This difference in volume becomes especially apparent when a rich diet causes the animals’ droppings to become a soft mass, similar to a domestic cowpie, but smaller.

“Elkpies” average 4- to 6-inches in diameter, while those of deer run about 2 inches across. Even when elk are eating mostly grass, elkpies will still show more distinct edges among the individual pellets than cowpies, which may be an amorphous mass.

Elk Rubs In late summer, as antler growth ceases, it finishes mineralizing and the blood supply to the velvet begins to deteriorate. This causes the velvet covering of the antlers to dry up and shred. As it dies, bulls begin to vigorously rub their antlers on shrubs and trees, to help rid them of the velvet. This rubbing behavior may also be the first ritualized use of the bull’s newly hardened antlers – it is quite noisy and attracts the attention of other elk.

It has been theorized that this “horning” of shrubs frequently causes shrub branches to be broken off and intertwined with the bull’s antlers, effectively making them look larger and more threatening to rivals and more impressive to potential mates. The rubbing also covers the bone-white antler with plant compounds that subsequently oxidize and stain the antlers to their characteristic dark brown color.

Regardless of the cause of this behavior, the result is obvious: small saplings and shrubs are left looking like someone with a hedge trimmer went on an angry rampage. In areas where elk are abundant, mangled shrubs and small trees are extremely obvious signs of the presence of bulls and their preparation for breeding.