‘This Nest of Dangers’: Two for the show

Published 10:29 am Tuesday, April 11, 2017

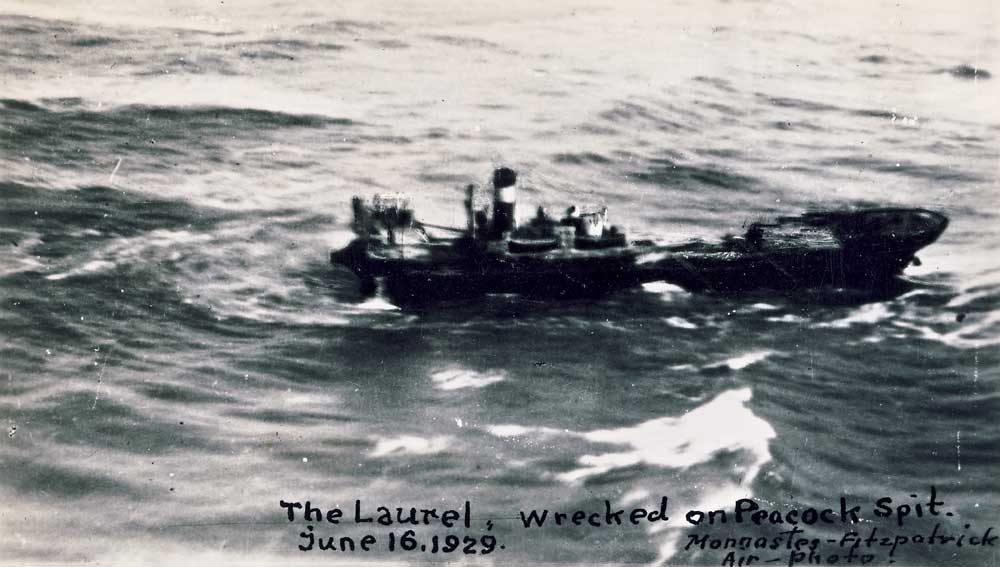

- Peacock Spit has trapped many vessels over the centuries, including the Laurel in 1929. Steady efforts by the Ilwaco Chamber of Commerce helped address deficiencies in local Coast Guard vessels of the time.

One day in February 1842 readers of the Baltimore (Maryland) Sun opened their paper to read of a shipwreck in the Columbia River, away on that far coast of the newly-expanded United States. It involved the first-ever, ‘round-the-world U.S. Exploring Expedition.

It was, indeed, big news.

Rumors about the difficulty of safely getting a ship over that cantankerous bar had drifted east; here in their hands was proof. The ships of the famous “U.S. Ex-Ex” were crewed by some of the very best sailors the new world had to offer. The Peacock had circumnavigated half the globe, in all kinds of seas, and now it had been battered to death on a domestic sandbar in temperate waters?

Good grief!

“Camp Peacock, Astoria, Columbia River, July 25, 1841. ‘On the 21st of June we left Honolulu, and arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River on the evening of the 17th of July.

“‘The following morning, (Sunday, 18th,) the usual religious service was performed, after which “all hands were called to work ship into port,” and in a few minutes we were close in with the breakers. …We had stood in not more than five minutes, when the ship suddenly shoaled her water and struck.

“‘Efforts were instantly made to get her by the wind and haul off; but a heavy sea and strong current rendered the attempt useless. The launch and first cutter were called away for the purpose of taking out a stream anchor and cable, and, no sooner was the cutter lowered than a heavy sea — rough wave — dashed her to pieces.

“‘The ship continued to forge into shoaler — shallower — water as the sea lifted her from the bottom, against which she thumped with great violence … Toward sunset a canoe attempted to come off to us from the Klatsop shore, near Point Adams, but did not succeed, owing to the heavy sea and thick fog which soon gathered around us.

“‘We fired signal guns of distress, and night soon closed from our view the terrific scene, while the heavy breakers continued to dash their utmost fury against our ship … . We ventured upon an awful night! the ship constantly thumping, … during the night many articles were thrown overboard for the purpose of lightening the ship; and it became evident that the water was rapidly increasing in the ship’s hold …

“‘As directed by the captain, I proceeded to collect my books and papers and “hold myself in readiness to leave the ship at a moment’s warning”…

“‘The heavy surging and constant crashing of timbers made the night a long and dreary one … It was near 7 o’clock in the morning of the 19th … [when we saw] a canoe … approaching, which got alongside as our boats were being lowered with men for the shore. It contained John Dean, and four Indians. … He expressed his regret that he had not been able to reach us in a canoe the previous evening ….

“‘The only propitious moment for leaving the wreck now presented itself … The boats were immediately despatched with both officers and men to the shore, a considerable portion of whom were landed before the sea set in again with violence. … [I]t was with the utmost pain we witnessed a boat’s crew … thrown violently into the sea, from which they were most fortunately extricated by … another boat … .

“‘Finding it impossible to reach the wreck, the boats now returned to the shore, while those of us still remaining on board were left in a most perilous situation … It may now be imagined what our feelings were … Towards evening another attempt was made by the boats to reach the wreck, and, after the most hazardous effort, they got alongside and rescued [us.]

“‘The Peacock was now left to her fate … The Captain was received, on landing, by the officer and crew, with three cheers, while all felt gratitude to God for his mercy in saving us. The Rev. Messrs. Feast and Kone, of the Methodist American Mission, and James Birnie, Esq., of the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Company, at Fort George, arrived with tents and refreshments, and a number of brush huts had been erected during the day. We had also saved two barrels of beef, two barrels of pork, and two barrels of bread, from the wreck. With the kind attention of these gentlemen and our own resources, we were rendered comparatively comfortable in our distressed situation — and, after partaking of some refreshments, we reposed, through a calm and serene night, in our humble habitations.

“‘The following morning, (July 20) at an early hour … I descended [sic] the bluff of Cape Disappointment to take a farewell look at what remained above water, of my good old ship, nay, my home, for three long years! As reported, the cap of the bowsprit was all that was visible! One sigh for the old ship that had borne me through many dangers, and I returned to the encampment.

“‘After an early breakfast, I proceeded, with my books and papers … for Fort George, Astoria …

“‘It may be well to state that nothing was saved from the wreck except the purser’s books, the clothes we had on, and the charts of our recent interesting cruise among the King’s Mill group of islands, &c. We are, therefore, ready for the latest fashions.’ ”

By 1846, the United States was feeling frisky, having won a war or two, and was beginning to believe that it had a God-given right to the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific, north of California, and south of the 54th Parallel. “Fifty-Four Forty Or Fight” was the popular political slogan of the day, and “Manifest Destiny” was the national mindset.

That spring the commander of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Squadron ordered a schooner to the Oregon County to size things up, to sail to the Willamette Valley, discover whether the residents there were pro-British or pro-American, and see if the Country looked profitable. It would be a short mission, lasting little more than a month.

The Shark, a U.S. Navy 2-masted schooner, was part of a small fleet able to frustrate the African slave trade and flummox pirates intent on seizing U.S. cargo in the Caribbean. The vessel was speedy and maneuverable and fairly small. Its commanding officer was Lt. Neil M. Howison, a gifted and diplomatic man well-suited to a politically sensitive task at the British regional headquarters.

Shark entered the Columbia in mid-July 1846 and proceeded upriver to Fort Vancouver. There Howison established amiable relations with the Hudson’s Bay Company management and the officers of the Royal Navy (stationed with their sloop-of-war H.B.M. Modeste), all the while remembering that his orders included ‘cheer[ing] our citizens in that region by the presence of the American flag.’

However, he soon found that he needed to calm “‘the excited state of public feeling which existed among the Americans … [that] it was my duty … to allay its exuberance, and advise our countrymen to await patiently the progress of negotiations [in the resolution of the War of 1812] at home.’“

Howison canvased the area, dispatching crew members up the Columbia to The Dalles and down the Willamette River valley. His 1848 report to Congress after his return home included turns of phrase and observations that interest us yet today:

“Besides Fort Vancouver, six sites have been selected for towns; of these Astoria takes precedence in age only. … It may be considered in a state of transition, exhibiting the wretched remains of a bygone settlement, and the uncouth germ of a new one. …

•••

“[W]e find from the seacoast to the Cascade range of mountains, an average breadth of 110 miles, a most vigorous natural vegetable growth; the forest trees are of gigantic stature …

•••

“Wheat is the staple commodity; the average yield is twenty bushels to the acre; and this from very slovenly culture. Those who take much pains, reap forty or fifty. … The quality of the wheat produced here is, I believe, unequalled throughout the world; it certainly excels in weight, size of grain, and whiteness of its flour, that of our Atlantic States, Chile, or the Black sea, and is far before any I have seen in California. …”

•••

“The first measure necessary [to help the Oregon Country prosper] is to render the entrance and egress of vessels into the mouth of the Columbia as free from danger as possible; and the first step towards this is to employ two competent pilots, who should reside at Cape Disappointment, be furnished with two Baltimore-built pilot boats, (for mutual assistance in case of accident to either,) and be paid a regular salary, besides the fees, which should be very moderate, imposed upon each entering vessel.

“A light-house, and some beacons with and without lights, would aid very much in giving confidence and security to vessels approaching the river; but more important than all these would of course be the presence, under good management, of a strong and well-built steam tug.

“The effects of these facilities would be to render certain, at least during the summer months, the coming in and going out of vessels, subtract from the premium on insurance, and give confidence to the seamen, who now enter for a voyage to Oregon with dread, reluctance and high wages.”

Howison’s analysis was on the money.

•••

Early in September Shark departed Fort Vancouver, then paused to help the HBC vessel Toulon work itself off a sandbar. By September 8th Shark was a week late leaving to join other U.S. Naval ships in anticipation of a conflict with Mexico. But before Howison could leave the River his crew was to survey the Bar to see how to cross safely — the five-year-old Wilkes survey was now out of date.

Someone bungled the job — Howison was out hunting elk for provisions — and the next day, the 10th of September, the Shark struck an uncharted shoal and was pulled into the breakers by the tide.

The Oregon Spectator of Oct. 1, 1846, carries Howison’s report which told a grim and familiar story. It concluded, “‘The conduct of the officers and men during the whole of this trying occasion was most praiseworthy, and to their cool exertions and orderly manner of carrying on the duty, may be principally ascribed the preservation of our lives. The wreck was completely untenable an hour after she was finally abandoned, and by 3 P. M., not a vestige of the poor Shark was visible.’ “

Howison and his crew built temporary housing in Astoria, were fed and comforted by the Hudson’s Bay Company (which send bread, tea and tobacco downriver to them immediately), and hitched a ride to San Francisco with the Cadboro.

The lieutenant then returned home to Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he crafted his report to Congress which he did not live to see published. He died of a “heart ailment” in February of 1848.

•••

When I read of Neil Howison’s efforts in and for this region, his exertions before and during the shipwreck of the Shark, his writing of the Congressional report after returning home, and shortly thereafter dying, I want to say that this dutiful man gave his life for his country in a way we don’t often recognize.

The Shark left part of herself behind: the cannons for which Cannon Beach, Oregon, is named and those installed at the Columbia River Maritime Museum. Also left behind, and in the collection of the CRMM, is an 1841 U.S. Naval officer’s dress sword.

Perhaps it is Howison’s.