Crossing the columbia river bar,

Published 1:55 pm Tuesday, March 14, 2017

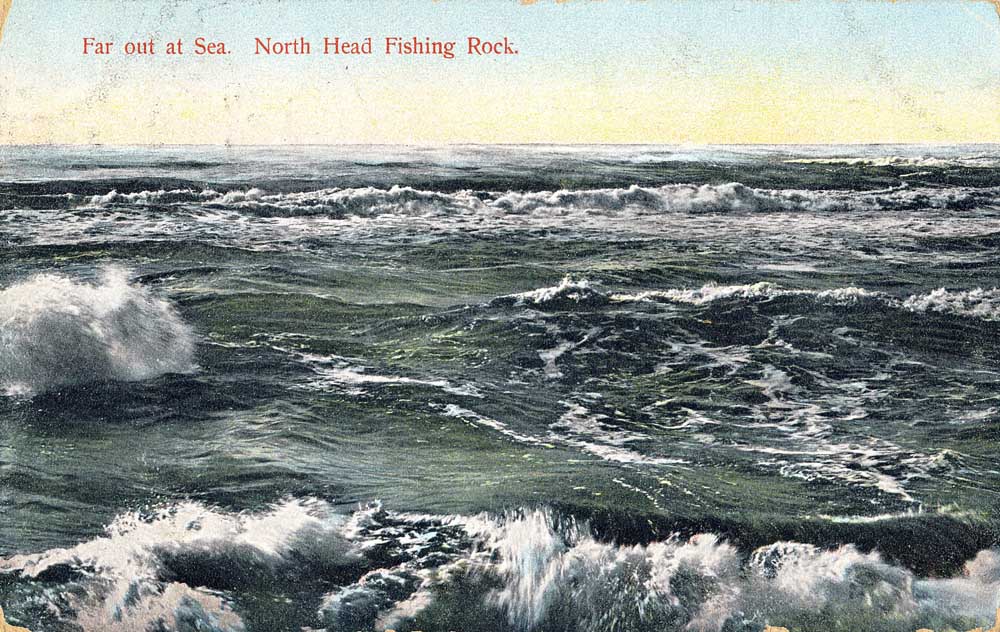

- A postcard from about 1905 shows the Columbia River plume on a relatively calm day. Ships often used to wait days in these waters for conditions to allow passage over the Columbia Bar.

Five months after Capt. Robert Gray’s vessel Columbia Rediviva crossed easily over the bar of the Columbia River in 1792, Capt. George Vancouver’s Lt. William Broughton brought the HMS Chatham over that same bar. Things were different.

Trending

One diarist on that voyage wrote, “We had a very fresh Breeze in our favour, but a Strong tide against us, which over the Shoals raised so very heavy and irregular a Sea, that it made a fair breach over us, and our Jolly Boat which was towing astern, was stove to pieces, and everything in her lost. …”

“I must here acknowledge,” the sailor wrote, “that in going into this place, I never felt more alarmed and frightened in my life, never having been in a situation where I conceived there was so much danger.”

This from a man who had helped sail wind ships at least half-way around the world.

Trending

The situation was no better on Chatham’s way out to sea:

“… The late bad weather had caused such a dreadful Swell over the Shoals at the entrance that we could observe no Channel free from Breakers … On the 10th [of November] and not before the Channel out being to appearance tolerably smooth … but we had scarce pass’d the Bar, when a tremendous Surf appeared rolling towards us, and broke over the Vessel with great violence, the Spray of it when it struck us, wetted the Foresail as high as the upper reef, the Main Deck was filled with Water fore and aft …”

“…(T)he Launch which was towing astern with a man in her, by the sudden violent motion of the Vessel and the force of the Sea, broke her Tow rope, which was a stout Hawser of four Inches [around], and instantly fill’d, we were in the greatest anxiety for a while about the poor fellow in her … “ The shipmate was rescued, but just barely.

Thus began to be noised abroad the Columbia Bar’s capacity for astounding violence, particularly in winter.

• • •

Six years later, in 1798, the brig Hazard was out from Boston hunting sea otters. As Capt. Benjamin Swift sought the path through the breakers into the Columbia River, he did what the Chatham’s captain and others had done and would do: he sent a small boat with a handful of men rowing and sounding depth to find the way for the ship to follow.

Sounding was done with a lead weight on the end of a line — a rope — marked with knots in succession indicating the length of rope that was out and hence how deep the water was.

Unfortunately, the Hazard’s jolly boat was capsized by rough water and its five crewmen were drowned.

When Lewis and Clark arrived on the Columbia coast in the winter of 1805 the water confronting them was stunning.

“Nov 16th 1805 … The Sea is fomeing and looks truly dismal to day …” [Clark.]

“Sunday December 1st 1805: “…The emence Seas and waves which breake on the rocks & Coasts to the S W. & N W roars like an emence fall at a distance, and this roaring has continued ever Since our arrival in the neighbourhood of the Sea Coast which has been 24 days Since we arrived in Sight of the Great Western; (for I cannot Say Pacific) Ocian as I have not Seen one pacific day Since my arrival in its vicinity, and its waters are forming [foaming?] and petially [perpetually] breake with emence waves on the Sands and rockey Coasts, tempestuous and horiable.” [Clark.]

Six years later, in March of 1811, John Jacob Astor’s maritime branch of his Pacific Fur Company arrived offshore, happy to see land — “the sight filled every heart with gladness” — until they got closer: “But the cloudy and stormy state of the weather prevented us seeing clearly the mouth of the river … the aspect of the coast was wild and dangerous …,” wrote company clerk Alexander Ross.

Capt. Jonathon Thorn of Astor’s ship Tonquin, ignoring the extreme state of the water and the weather, ordered his first mate, Mr. Fox, to examine the Columbia’s channel, sending him out into nature’s elemental din with an inexperienced crew of four.

Ross continues, “Mr. Fox then represented the impossibility of performing the business in such weather, and on such a rough sea, even with the best seamen, adding, that the waves were too high for any boat to live in. The captain, turning sharply round, said — ‘Mr. Fox, if you are afraid of water, you should have remained at Boston.’

[Nice guy.]

“On this Mr. Fox immediately ordered the boat to be lowered, and the men to embark. If the crew was bad, the boat was still worse — being scarcely seaworthy, and very small. …

“… [W]e often lost sight of the boat before she got 100 yards from the ship; nor had she gone that far before she became utterly unmanageable, sometimes broaching broadside to the foaming surges, and at other times almost whirling round like a top, then tossing on the crest of a huge wave would sink again for a time and disappear altogether.

“At last she hoisted the flag; the meaning could not be mistaken; we knew it was a signal of distress. At this instant all the people crowded round the captain, and implored him to try and save the boat; but in an angry tone he ordered [‘]about ship,[‘] and we saw the ill-fated boat no more. …”

Ross describes the next attempt to get the Tonquin across the bar.

“…After passing an anxious night [after an unsuccessful attempt to enter the River], the return of day only increased the anxiety, and every mind was filled with gloomy apprehensions. In the course of this day … and the weather becoming calm, Mr. M’Kay, Mr. David Stuart, myself, and several others, embarking in the long boat [an open boat propelled by oars and a handful or two of men] … stood in for the shore …

“On approaching the bar, the terrific chain of breakers, which kept rolling one after another in awful succession, completely overpowered us with dread; and the fearful suction or current became so irresistibly great, that, before we were aware of it, the boat was drawn into them, and became unmanageable: at this instant, Mr. Mumford, who was at the helm, called out, ‘Let us turn back, and pull for your lives; pull hard, or you are all dead men.’

“In turning round, the boat broached broadside to the surf, and was for some time in imminent danger of being engulfed or dashed to pieces; and … we were for twelve minutes struggling in this perilous situation, between hope and despair, before we got clear …

“Notwithstanding our narrow escape, we made a second and third attempt, but without success, and then returned to the ship. …

“During this time the ship [Tonquin] was drawing nearer and nearer to the breakers … the sight of which was appalling. On the ship making the first plunge, every countenance looked dismay[ed]; and the sun, at the time just sinking below the horizon, seemed to say, ‘Prepare for your last.’

“… The water decreasing from 8 to 2½ fathoms, she struck tremendously on the second reef or shoal; and the surges breaking over her stern overwhelmed everything on deck. Everyone who could, sprang aloft, and clung for life to the rigging. The waves at times broke ten feet high over her, and at other times she was in danger of foundering: she struck again and again, and, regardless of her helm, was tossed and whirled in every direction, and became completely unmanageable.

“Night now began to spread an impenetrable gloom over the turbulent deep. Dark, indeed, was that dreadful night. We had got about a mile into the breakers, and not far from the rocks at the foot of the cape [Disappointment], against which the foaming surges wreaked their fury unceasingly. Our anxiety was still further increased by the wind dying away, and the tide still ebbing.

“At this instant, someone called out, ‘We are all lost, the ship is among the rocks.’ A desperate effort was then made to let go the anchors — two were thrown overboard; the sails kept flapping for some time: nor was the danger diminished by learning the fact that the surf dragged ship, anchors, and all, along with it.

“But there is a limit to all things: … the tide providentially beginning to flow … [and] brought about our deliverance by carrying the ship along with it into Baker’s Bay, snug within the Cape, where we lay in safety. …”

These reports are exhausting to read.

Of course, it is not always that rough.

Now in the winter of 2017 as I sit here on shore and read, occasionally hearing out of the night’s silence the sledgehammering of breaking waves on sand and rock, I cannot imagine how, in old days or new, men found — and find — their way through it all to go about their business.

Pause this time of year and think kindly of the crab fishermen whose sodium vapor lights you see out there in the nighttime darkness.