Editor’s Notebook: Sacrificing an aspen to Apollo

Published 8:51 am Thursday, July 11, 2019

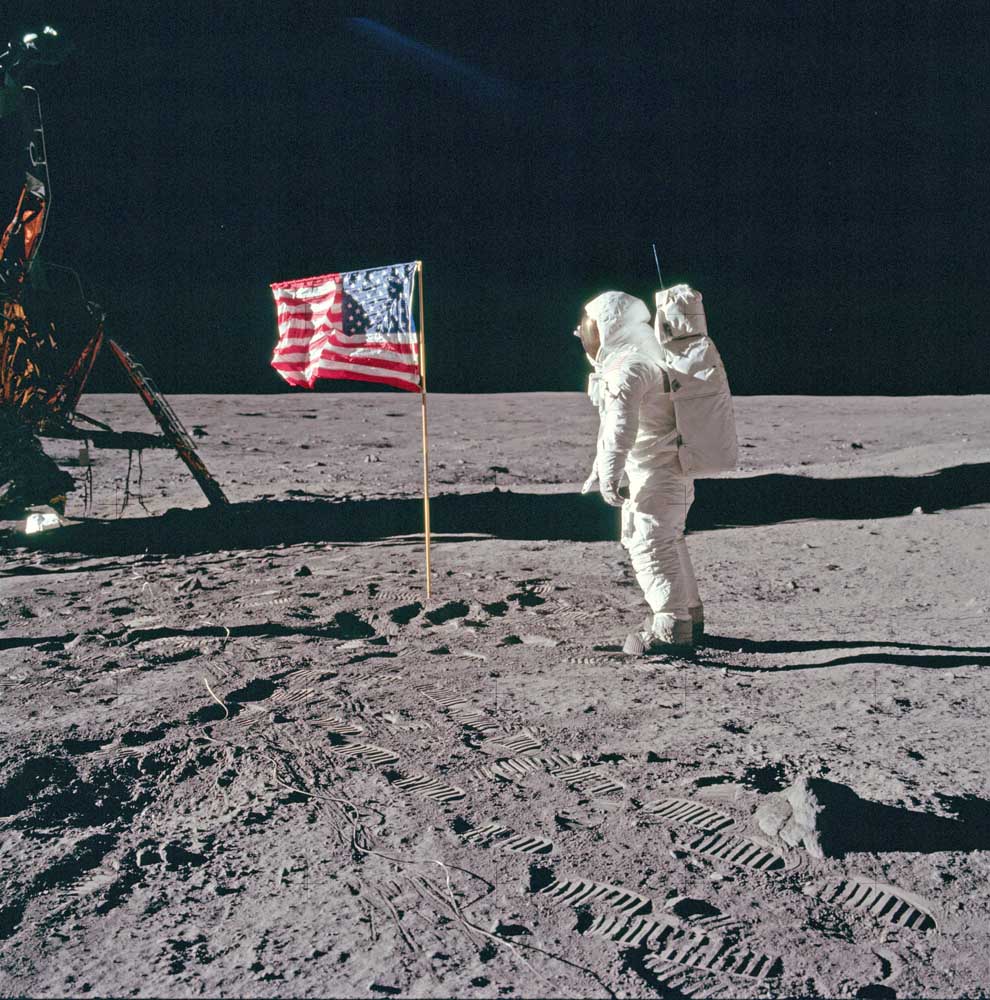

- Buzz Aldrin salutes the deployed U.S. flag on the lunar surface 50 years ago.

I was 11 when Apollo 11 landed on the moon. We all figured by now plenty of people would be living there in pressurized trailer parks, taking giant leaps for mankind.

With so many having left to colonize the solar system, I fantasized about staying behind on an emptier planet. My true love and I would live like Marlon Brando and Lauren Bacall on a private tropical island, our laughing children looking skyward to admire the moon’s city lights on warm summer nights.

What do 11-year-olds aspire to these days, anyway? Getting rich has always been a popular target and surely remains so. Also still a mainstay is lusting after fame — in reach for a lucky few who are clever enough or rude enough on social media.

Aside from that, there doesn’t really seem to be any overarching theme for dreams. Farfetched fantasies ought to be a birthright for every child.

My “world” — a small Wyoming mountain town — was far safer than the world 11-year-olds know now. We were snug as bugs in a rug, to use a nostalgic expression. We had both room and reason to dream big, being four and a half hours from the nearest big metropolis, Salt Lake City. The moon seemed nearer.

An unlucky aspen

A day after the Apollo 11 landing, my friend Cale Case and I were down by my family’s river bank 500 yards from our house, thoroughly caught up in the excitement of what had happened.

To commemorate the occasion we carved a message in the bark of a poor aspen, something like “Yesterday, July 20, 1969 humans first landed on the moon — JCC MSW.” (It’d be fun to go back and find the tree, except that our commemoration may have killed it.)

Cale, always a happy prankster, joked around and said the word “help” in little more than a conversational tone of voice and about two minutes later my worrywart dad came crashing through the brush to rescue us from the savage bear or whatever it was that had us. He was angry and perhaps just a little disappointed to find his heroics unneeded. Aggravating as his attention could sometimes become, it was a comfort knowing I had a dad within earshot if I ever really needed help. His memory still holds me upright in times of need.

He was indulgent when 14-year-old me presented detailed plans for a dirigible/airship that I intended to fly down the Americas and over Antarctica. That indulgence didn’t extend to writing a check for requested aluminum alloy ribbing, but we did take flying lessons together, and I did eventually fly hot-air balloons. And Cale used to fly his plane down to Cheyenne, where he’s still in the state Senate and probably has little fun at all.

The dream drought

The dreams and well-being of children are one of the best measures of the health of society. America is still a good place to live despite our disagreeable politics. But on this little old world there are too many places without hope — gnawing tragedies that send thousands crashing against our increasingly unfriendly borders.

Even in our lucky nation, there are too few dreams and too much pessimism. Could it be that the millions we spent on the moon missions were a small price to pay for a sense of direction?

Privately funded space exploration probably is our next real chance of stretching beyond earth. This makes sense. Realistically, unless people can make money in return for taking enormous physical and financial risks, most of would rather stay home.

Although I haven’t “read” science fiction since age 15 or so, in the past couple years I’ve started listening to it while walking the dog and doing yard work — thanks to Audible, the Amazon-owned spoken book company. “The Singularity Trap” by Dennis E. Taylor held my attention a few weeks ago, laying out a plausible scenario in which private entrepreneurs mine metallic asteroids.

For working people on the book’s fictional earth, it has become one of few ways to break out of poverty, heat and congestion.

Similarly, PBS’s Nova recently outlined preliminary plans to use the moon as a stepping stone to more-distant destinations — converting its surprising quantity of water into hydrogen and oxygen fuel for rocket ships.

Sacred and sacrosanct

Moon is a friend I miss seeing during our season of storms. But even in those terrible hours when it sounds like ravenous banshees are successfully clawing their way through my darkened window glass, it’s comforting to know the moon is still calmly shining just above the fray. If only my battered old pickup were capable of driving straight upward, I could glimpse her above the clouds in just a minute or two at highway speed.

The movement of both the sun and moon have been compared to pendulums, majestically swinging through the days and seasons with rhythms our ancestors believed to reveal the secret mind of god. Who are we to say they were wrong?

We’re just past summer solstice, when the sun’s annual pendulum is at the top of its arc and just gaining momentum toward fall equinox — Sept. 23 this year. Like a pendulum, as the sun nears and passes solstice, it stalls in its progress along the horizon and down the sky.

The word solstice literally means “standstill of the sun.” After its current near-pause, it will begin racing back toward fall like a Hot Wheels car on a slick plastic track.

Part of me intensely prefers to preserve our ancient relationship with the moon as it sails sacred and sacrosanct through the seasons. Will it still shine as bright when the first strip mines open there? Probably. But will boys and girls still look upon it with awe?