This Nest of Dangers: The W.H. Besse’s unforgettable tale

Published 9:54 am Thursday, April 11, 2024

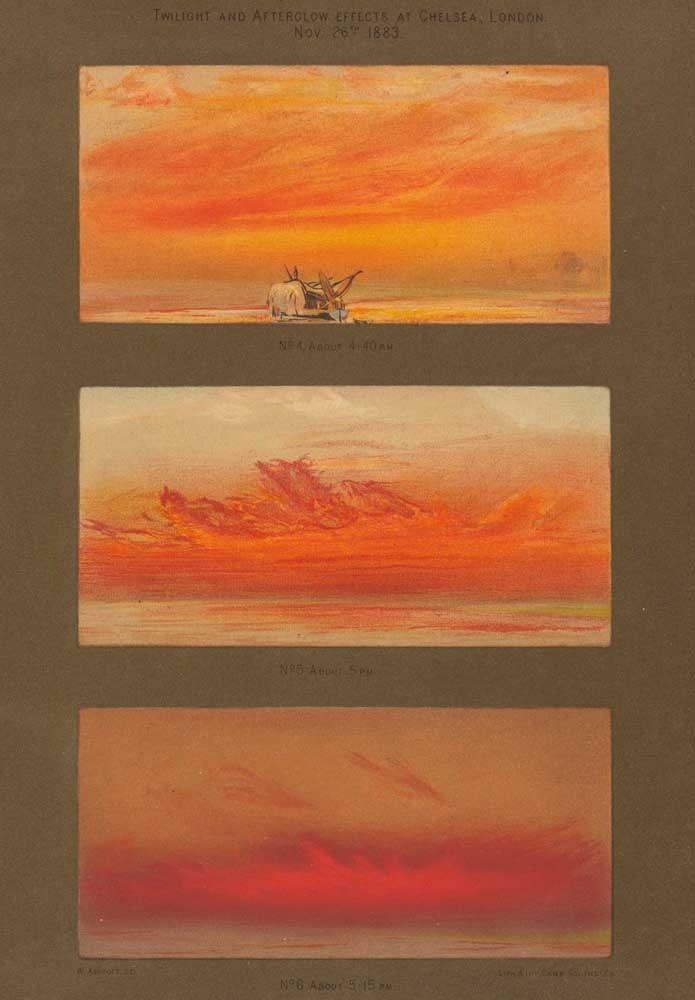

- Soot and gases emitted by the Krakatoa eruption resulted in colorful skies worldwide.

Five years ago, about this time of year, the Observer published my essay about the sailing bark Alden Besse. That vessel, a Maine-built American clipper, sailed in the western waters of the Pacific and lived, for a ship, a long life. She ended her days as a film star in several silent movies, most notably “The Mate of the Alden Besse.”

Trending

At the time, I glossed over the wreckage of her fleet-mate W.H. Besse at the mouth of the Columbia. Recently I had reason to revisit that vessel and found a fascinating backstory.

”Grounded’

In July 1886, The Morning Oregonian reported, “The bark Wm. H. Besse grounded on North spit last night. The captain and crew abandoned her and are safe. The vessel is breaking up this morning, and fast disappearing. She will be a total loss. She had no pilot on board.

Statement of Capt. Gibbs:

We sighted Cape Hancock [Cape Disappointment] at 12 M, the 23d inst., the lighthouse bearing east by north about twenty miles distant. Set the jack for a pilot. At 6:20 p.m. no pilot-boat or tug was in sight. Cape Hancock bore northeast, distant about two and a half miles.

While wearing the ship to stand off shore, the ship’s stern struck and the vessel swung round on which I have since heard is called the north spit of the middle sands.

According to accurate cross-bearings on my chart, the ship’s position then was one mile distant and outside the Bar. I immediately braced the yards round to work her off.

As soon as the ship struck she commenced pounding heavily. There was a heavy swell on, but a light wind.

Ten minutes after she struck I sounded the pumps and found four feet of water in the hold. The ship was thumping so heavily that it was impossible to stand upright on deck. The masts were shaking violently, and the rigging falling.

‘The howling of the wind through the rigging formed one of the wildest and most awful scenes imaginable — one that will never be forgotten by anyone on board — all expecting that the last day of the earth had come.’

Ship’s logbook of the W.H. Besse, recording one of the most destructive volcanic eruptions in recent centuries

All efforts to save the ship were evidently useless, and as the life of the whole crew was endangered I gave orders to clear away the boats. The port boat swamped alongside, I losing the ship’s chronometers, nautical instruments and all my personal effects.

All hands took the starboard boat … and abandoned the ship about 7 p.m.

We landed at Fort Canby … and got the life boat and crew to go back to the ship with me and some of my men to see if we could save any of the ship’s effects. We found the ship listed to windward, the seas making a clear breach over her.

We could do nothing, so we returned. At daylight of the 24th the ship’s masts were gone by the board and the vessel breaking up fast.

The Oregonian’s article concludes, “The W.H. Besse sailed from New York February 18, with a cargo of rails, spikes, etc., for the O. R. & N. Company, to be used on the Farmington branch, now under construction. Her cargo was valued at $70,000, and was no doubt insured … Her owners are Captain W.H. Besse and associates, and her value is between $40,000 and $50,000. … The Besse is wood, and was built at Bath, Maine, in 1873. … Her registered tonnage is 1027. The vessel was surveyed at Boston in January 1884 and was rated A-1. Her master, Captain Gibbs, was on his third voyage to Portland and is accounted a very competent seaman.”

Terrible disaster

From an 1885 journal entitled Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria [of Melbourne, Australia] comes an article headlined, “Experience of the Barque W.H. Besse in the Java Earthquake, August 1883,” by G.H. Ridge.

“Some days ago Captain Gibbs, of the American barque W.H. Besse spoke to me of his experience in the Java earthquake (he being at that time chief officer). The vessel was on a voyage from Manila to Boston. I thought that any information I could obtain of such a terrible disaster would be of interest to the members of the Royal Society …

“On looking at the chart of Sunda Straits [the waterway between the Dutch East Indies islands of Java and Sumatra], although they had only been partially re-surveyed at the time the W.H. Besse left Boston for Melbourne, I found that a large portion of Krakatoa Island had been submerged; two new islands and a large reef have appeared where deep water was previously indicated. …”

From the [ship’s] log-book:

Friday, 24th August. Off Amsterdam Island. Moderate winds and cloudy weather; barometer 30.14, thermometer 95.

Saturday , 25th August. Moderate winds and fine weather; barometer 30.15, thermometer 90.

Sunday, 26th August. The day commenced with strong breezes and thick, cloudy weather, barometer 30.15. … At 4 p.m., wind hauling ahead, came to an anchor, the sky at this time having a threatening appearance, atmosphere very close and smoky.

At 5 p.m. heard a quick succession of heavy reports sounding like a broadside of a man-of-war, only far louder and heavier; heard these reports at intervals throughout the night. The sky was intensely dark, the wind having a dull moaning sound through the rigging; also noticed a light fall of ashes.

The sun, when it rose the next morning (Monday, 27th August), had the appearance of a ball of fire, the air so smoky [I] could see but a short distance. At 6 a.m., thinking the worst of the eruption was over (as the reports were not so frequent or heavy as during the night), got under weigh.

Having a fair wind, was in hopes to get out clear of the Straits before night. At 10 a.m. were within 6 miles of St. Nicholas Point, when we heard some terrific reports; also observed a heavy black bank rising up from the direction of Krakatoa Island.

The barometer fell an inch at once, suddenly rising and falling an inch at a time.

Called all hands, furled all sail securely, which was scarcely done before the squall struck the ship with terrific force. Let go port anchor and all the chain in the locker; wind increasing to a hurricane. Let go starboard anchor.

It had gradually been growing dark since 9 a.m.; by the time the squall struck us it was darker than any night I ever saw — this was 12 o’clock noon.

A heavy shower of ashes came with the squall, the air being so thick it was difficult to breathe; also noticed a strong smell of sulphur — all hands expecting to be suffocated — the terrible noises from the volcano, the sky filled with forked lightning running in all directions, making the darkness more intense than ever.

The howling of the wind through the rigging formed one of the wildest and most awful scenes imaginable — one that will never be forgotten by anyone on board — all expecting that the last day of the earth had come.

The water at this time was running by us in the direction of the volcano at the rate of twelve miles an hour.

At 4 p.m. wind moderating, the explosions had nearly ceased, the shower of ashes was not so heavy, so was enabled to see our way round the decks.

The ship was covered with tons of fine ashes resembling pumice-stone. It stuck to the sails, rigging, and masts like glue, so it was weeks before it was removed, some of it still remaining on the wire back-stays. …

All day Tuesday, 28th August, crew were employed in shovelling the ashes off the decks, clearing the cables, and heaving up one anchor.

Wednesday afternoon, 29th August, got under weigh.

Was abreast of Anger [sic] at 8 in the evening; saw no lights on shore or signs of life. Although a fair wind, furled all sail but topsails. Kept on our course slowly, and cautiously heaving the lead every few minutes.

At daylight the Straits were covered with trees, so it was difficult finding a passage through them. Passed a large number of dead bodies and fish, and thousands of green cocoanuts. At 6 p.m. were outside of the Straits.

The ocean for 600 miles was covered with ashes and lava, the water for 1000 miles having a dull grey colour.

Five of the crew were taken sick with the Java fever the day after leaving the Straits. Buried one man at sea.

After rounding the Cape [Cape Horn] experienced a very heavy gale in the Gulf and bad weather on the coast, with only five men to work the ship, and those completely laid up by the time we got a pilot on board off Highland Light [on Cape Cod], one seaman dying the day after we arrived, and several more going to the Hospital.

So, three years before the W.H. Besse sank at the Columbia River Bar, this sturdy vessel survived the nearby volcanic eruption of Krakatoa, the most explosive and deadly in written history. It seems a wonder that ship wasn’t sunk by the heavy ash fall or by corresponding giant waves and hurricane winds.

Nightmares

Those of us who experienced the sobering secondary outburst of Mount St. Helens a week after the major eruption of May 18, 1980, will never forget the effect on us. That light dusting of ash congested my lungs and scratched the glass of my car. I thought the Peninsula’s tourist economy was at an end.

The surviving crew of the Besse must have had nightmares the rest of their lives … Krakatoa’s eruption and this vessel’s voyage through the results is unimaginable. …

And what does it say about this ship captain, who was able to lead his crew and vessel out of Hell that day … Only to lose it on the wretched Columbia River Bar.