UW scientists foresee wolves in S. Cascades, Olympic Peninsula

Published 8:30 am Monday, February 28, 2022

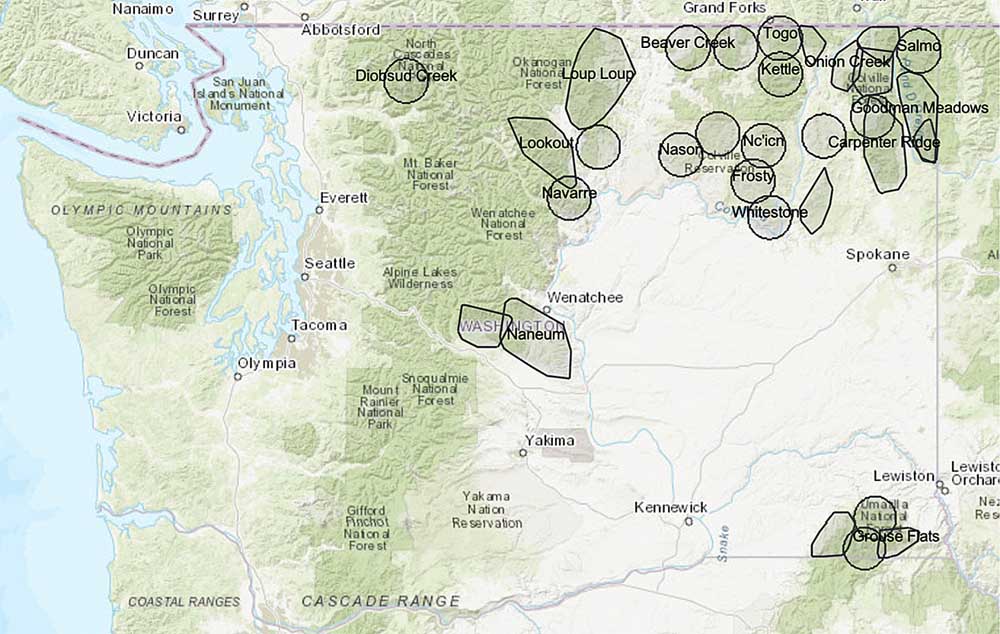

- Washington’s wolf packs are shown as of February 2022. Wolves are expected to eventually expand to the west and south.

Wolves likely will colonize the South Cascades and Olympic Peninsula and outnumber wolves in Eastern Washington within 20 years, according to University of Washington researchers.

Trending

‘We can see populations are going to grow, grow, grow.’

Lisanne Petracca

UW conservation scientist

UW conservation scientist Lisanne Petracca cautioned that the predictions are far from certain, especially the timing. Researchers are confident the state’s wolf population will grow, but are less sure how fast wolves will spread.

Nevertheless, wolves can be expected to disperse west and settle in greater numbers than now seen in northeast Washington, Petracca told the Fish and Wildlife Commission on Feb. 19.

“We are pretty certain that wolves will begin to establish in the Southern Cascades and the northwest coast, and that they apparently will come to outnumber wolves elsewhere,” she said.

50-year forecastUW scientists and statisticians, aided by Fish and Wildlife biologists, are trying to project the growth and spread of wolves in Washington over the next 50 years, inserting science into politically charged wolf management.

Washington’s wolf population has increased yearly in the past decade and wolf packs saturate northeast Washington. Wolves, however, have been slower to spread west than expected by Fish and Wildlife.

No wolf packs have been documented in the South Cascades or Olympic Peninsula, though both forested areas are considered prime wolf habitat.

Even so, wolves may be more numerous in Western Washington by 2040 and outnumber wolves east of the Cascades 2 to 1 by 2070, according to the UW research.

15 scenarios

In a preliminary presentation on the project, Petracca said researchers built a population model to project 15 different scenarios.

A baseline scenario assumed no changes to wolf management or survival rates. Researchers also assumed that highways, people and terrain would not stop wolves from seeking their preferred habitat.

The baseline scenario suggests “that if things just continue as they are that we’re more certain than not that in 20 years, wolves will be on the Peninsula,” Petracca said.

Another scenario assumed Fish and Wildlife will kill more wolves to protect livestock in northeast Washington. Under that scenario, wolves would still colonize the South Cascades and Olympic Peninsula, she said.

Petracca repeatedly stressed that the modeling results are not firm forecasts. “It’s really difficult, actually, to try to build a model and estimate where wolves will go,” she said.

“We truly have no idea how and when wolves will get to the South Cascades, into the Peninsula. We can try to estimate that as best we can, but it’s really hard to do it,” she said.

Fish and Wildlife and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation counted 178 wolves in 2020, the latest tally.

By 2070, the wolf population could be about 500 and perhaps as many as 2,000, Petracca said. “We can see populations are going to grow, grow, grow.”