Long Island: Natural paradise in plain sight

Published 9:01 am Monday, March 28, 2022

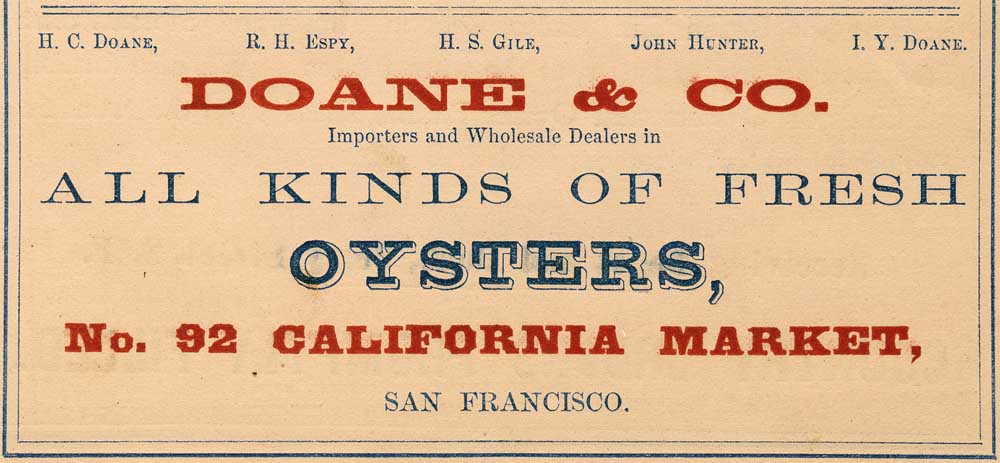

- In 1867, Isaac Doane of Doane & Co. established an oyster station at Diamond City on the northern tip of Long Island. This advertisement in a San Francisco directory dates from 1872.

Chinook living sites were once located on Long Island in Willapa Bay — now one of the largest uninhabited islands on the mainland West Coast. The island was also a refuge for Indian people who had been pushed off their traditional living sites by Euro-American settlers. Chinooks traditionally fished, dug clams, gathered oysters, and hunted on the island. Sam Pickernell, who now lives in Bay Center, is said to be the last of the Chinooks to have lived on Long Island, on the northern end.

On the west side of the island are large areas of intertidal meadows of eelgrass. The eelgrass provides nursery grounds for young fish — herring, salmon, seaperch and sole. A good place for hunters, the area is also an important food source for black brant, Canada geese and ducks.

The east side of the island is home to tidal marshes and rich oyster grounds. Many kinds of birds have always been found — herons, shorebirds and ducks feed off the rich vegetation. Here plants die, decay, and are recycled into the bay where they decompose and are covered with bacteria and algae.

Both the area on and around Long Island is home to large numbers of raccoon, mink, muskrat, rats, mice and coyotes. Black-tail deer, black bear, and elk also make their home here. Besides the numerous Canada geese and black brant, there are whistling swans, scoters, buffleheads, scaups, grouse, band-tailed pigeons, mallards and mergansers. Among the predators and scavengers are crows and ravens, red-tailed hawks, Cooper’s hawks, sparrow hawks, duck hawks, ospreys and eagles.

Oysters and Diamond Point

In 1867, Issac Doane established an oyster station at Diamond Point on the northern tip of the island. Situated near the native oyster beds, and never exceeding more than 75 inhabitants, the oystermen deserted the settlement after the oyster harvest plummeted to record lows in 1879. The camp had been given the name “Diamond City,” supposedly for the glittering reflection on piles of oyster shell seen from across the bay at Oysterville and Nahcotta.

Over the years a number of people inhabited the island’s north end. Brothers Fred and Frank Katzer bought the Diamond Point site in 1900, tearing down what was left of the oystermen’s shacks from some 25 years earlier. After Frank died, and as Fred grew older, he remained in the oyster business, even after the beginning of the Japanese Pacific oyster era. All through the failure of the eastern oysters, Fred kept his oyster ground and equipment, escaping the failure a lot of small owners suffered. Needing help as he got older, Fred met Erling Bendiksen, who was looking for someone to supply him with a boat and a loan to get started in the oyster business. Some say it was a marriage made in hell. For Erling Bendiksen and Fred Katzer it was the perfect fit.

In 1975, Harlan Herrold talked about the tight-fisted Norwegian, Erling Bendiksen.

Fred Katzer was getting old and couldn’t do anything, but he had an old boat and a ferry. He couldn’t get out and hit the bed work himself anymore, then he got mixed up in the Japanese business on shares, he had the ground and things. His ground hadn’t gone for taxes. Then he hired Erling Bendiksen to work his oysters for him, work on the beds, that’s the first time I ever saw Bendiksen, about 1934.

Bendiksen got going, being a regular bulldog, he hung on, but he had the faculty there and that was awful hard to cope with. He kept going, fishing in Alaska and working on the oysters here. Everybody felt sorry for poor Bendiksen … He owed everybody in the damned country, but poor Bendiksen, he’ll pay, he’s good for it, he’ll pay when he gets around to it, when he gets the money … Stores squealed like hell, but they would hold his bad checks … You couldn’t hurt him, whatever you said never hurt him … Everyone felt sorry for poor Earl.

Frank Katzer died around 1908, but long before Erling Bendiksen had come along, Fred had remained on his Long Island property; and around the beginning of the first World War he advertised for a marriage partner to come live with him at his island home.

A Scottish woman, who arrived in Seattle for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, answered the advertisement, met Fred, and married him. After a few brief years Mrs. Katzer died. The versatile Fred then sent for his deceased wife’s niece, who still lived in Scotland.

According to an entertaining story, Fred sent the niece a photograph of a younger, handsome man which was not Fred. Fred certainly did not fit that description, as he wore a beard to hide a very receding chin. When she came to Willapa Bay, the younger woman felt some betrayal, but did not want to return to Scotland. Although she agreed to marry Fred, he was soon persuaded to move his spouse from the island to a more comfortable home in South Bend.

Fred purchased the old 24-room Nahcotta Hotel, a building which was 84 feet long, 32 feet wide, and completely surrounded by an eight foot porch. The hotel was moved to South Bend in June 1924 by loading it on a scow owned by Capt. A. W. Reed. En route to South Bend, Reed and his crew slept and dined in the hotel. After dealing with some delay and repairs of a broken timber, the hotel was placed on lots across from South Bend’s Carnegie Library. (The barging of houses and buildings around the bay was not unusual. For example, the old Heath & Cearns hardware store in South Bend had originally been the Drissler & Albright store in Willapa City, before being barged over in the 1890s.)

The Katzers turned their old hotel into an apartment house that they also lived in. It was generally known that the young Mrs. Katzer had a special penchant for new cars. The early car dealers of the area returned the lady’s passion by paying close attention to her desire for a new model every year, sometimes twice a year. Mrs. Katzer outlived her husband by many years and is well remembered by several old-time South Bend residents.

Mr. and Mrs. Moritz Kramer also lived at Long Island, on a small farm on the island, until Kramer’s premature death in the fall of 1920. (Moritz died of a heart attack at the age of 48.) A native of Sweden, Kramer earlier had worked at the Columbia Box Mill as a grader and talleyman. After marrying, the couple moved to Long Island where they raised cattle, hogs, and maintained a vegetable garden and small fruit orchard.

High Point

At the southern tip of the island, during the late 1880s, there was a short-lived salmon cannery called the Northwestern Canning Company. The company operated around the same time as the early canneries at Bay Center, North River and South Bend. For economic reasons the island packing house was gone before 1892.

Donald Ross, Edward Jensen and Smoky Johnson were three of the island’s homesteaders to stay for any length of time. Ross erected a plain and square-shaped English-styled house, perched above High Point, at the southern tip of the island. The house became a landmark, in full view of U.S. Highway 101. The place seemed mysterious, both from its remote location and its mansion-like appearance, and was abandoned by the time the island began to be designated as a wildlife refuge in the late 1930s.

Ross died before 1900 and Mrs. Ross sold the property and house to J. M. Arthur, who owned The Breakers Hotel at Long Beach. Arthur used the house as a hunting lodge and brought wealthy guests to the island for hunting expeditions. The next owner was Fred Reiff, a fisherman who lived in Chinook. Reiff bought the Arthur property in 1919 and sent to Germany for a bride to join him. The Reiffs were the last owners when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service bought the place in 1937.

The wildlife service tore down the house in 1954 and planted a 10-acre grain field for the migratory birds. Unfortunately, the wildlife workers did not build a fence, and the first planting of barley, clover and orchard grass was more enjoyed by the island’s black-tailed deer and elk, rather than the migratory birds. After building a fence the next year, livestock grazed on the grasses before the arrival of the birds.

Logging

During the 1880s, lumberjacks extensively logged the island, with the timber sawed at the Sunshine Mill. In the early 1900s Charles Funk logged at several places around the bay, including the Nemah, the Cedar River and North River. Funk had a string of float houses which he took to Long Island. Since the Sunshine Mill had closed years before, log booms were towed to both the Raymond and South Bend mills. Another early camp belonged to the Pentilla Logging Company.

Workers and visitors could reach Funk’s floating camp by the mail boat that served the Nahcotta-Naselle route. A Funk daughter remembered getting off the mail boat at Chetlo Harbor, where her father would meet her. Funk’s earliest operation on Long Island lasted until the bayshore highway was completed in 1922. Later, after the wildlife refuge began taking over the island, Funk moved his houseboat camp to the Cedar River.

The Herbert Nelson family also lived on the island, where son Chris (of the Nelson Crab Cannery) was born in 1914. For a time Nelson operated a gravel business on the west side of the island. Nelson transported a considerable amount of gravel to the new Ocean Beach highway project during the 1920s. Nelson also logged on the island, but the economic problems of the late 1920s closed the operation. The Nelsons moved to South Bend, where they lived before discovering the possibilities of the crabbing business at Tokeland.

In 1955, J. G. Vasey, a logging operator from Portland, cut hemlock and spruce on the north side of the island, loading the logs across the channel from the wildlife headquarters. The Wildlife Service later charged Vasey with “inexcusable laxity” for his failure to remove standing snags on the logged off areas. The Washington State Division of Forestry penalized Vasey with a small fine, but a portion of it was removed after the logger removed some of the snags. (Many snags are now regarded as valuable wildlife habitat.)

In March 1955, soon after Vasey started logging on the island, Everett Rogers, from South Bend, signed an agreement with the government’s agency. Rogers removed timber from the east side of Long Island, on Baldwin and Sawlog (aka Caffee) Sloughs. During this period, more than a million board feet of timber was sold (hemlock and spruce). Timber removed from the refuge was yarded on upper Baldwin Slough.

In November 1955, newly purchased heavy equipment was frozen and lost during an unusually cold spell. Stressed because of the loss, Rogers suffered a fatal heart attack at the refuge boat dock on Dec. 5. The logging operation ceased as of that date, but the Rogers’ estate later removed timber under the terms of the five-year land-for-timber exchange agreement between the two parties. During the summer of 1956 timber was cut and sold. The sale came to 17 log rafts shipped to the Weyerhaeuser Company.

Following the Columbus Day storm of 1962, a salvage program of blown-down federal and private timber was begun. It was at this time that a ferry system was started to transport equipment and trucks. In 1983 a land-for-timber exchange with Weyerhaeuser Company gave the refuge ownership of more than 1,600 acres of land, including the 119-acre old-growth western cedar grove. In the following two years, funds were appropriated by Congress to purchase another 155 acres of the ancient cedar grove. From 1984 to 1986 approximately 880 acres of timber were logged on the island. Since then there has been no logging on the island. The ferry line was removed in the 1990s.

Presently, the 274-acre ancient cedar grove is one of the last remnants of the coastal forest once common in southwestern Washington state. The island’s moist climate and its location has protected the centuries-old cedar trees from forest fires, as well as clear-cut logging. Growing among the big cedars are many western hemlock.

Towboats

From the turn of the 20th century there were several towing companies working the south end of Willapa Bay, including the Naselle and Nemah rivers. In the 1920s and 1930s, Carl Gylling owned and operated the Nemah Towboat Company (as part of Hart-Wood of Raymond). Later, Denzel Schultz skippered the towboat Nemah. (The Schultz family also operated the Schultz ranch on the Nemah and the Nemah Dairy of Raymond).

John Whitcomb also worked the area. Whitcomb sold the Transit to Stanley Nielsen. Later, Nielsen joined with Ed Triplett in the 1940s to form the Willapa Harbor Towboat and Dredging Company. At that time the new company had two boats — the Transit and Triplett’s Standard. Within a few years there were three more boats added to the roster — the Fearless, which the men purchased from Harry Nielsen (Stanley’s father); the Daring, purchased from Olympic Hardwood; and the Sunbury, which they acquired from the Hubble Towboat Company. The 53-foot Sunbury had originally been the steam-powered Agnes, owned by the Coulter Towing Company 25 years earlier. As Ed Triplett recalls, the Sunbury was the most powerful of the five boats, “It had a big ‘jimmy.’”

After buying out Stanley Nielsen around 1980, Triplett expanded his business to include hauling gravel out of Long Island, similar to the 1920s operation of Herb Nelson. Triplett used a clamshell shovel and barges to haul gravel from the High Point area to Nahcotta. Most of the Peninsula’s Sandridge Road was constructed with Long Island gravel hauled by Ed Triplett’s company. Ed laughs when he recalls the gravel operation. “Yeah, we found a lot of real good little-neck clams over there, too.”

The towing is now gone — and the boats were either scuttled or sold to Puget Sound boat enthusiasts. One remain as of 2003 — the Dan Louderback-built Daring, alongside the Herrold family dock at Cougar Bend. The Sunbury was “junked out,” as was the Standard, but the Fearless and Transit still live, on Puget Sound.