Editor’s Notebook: Salmon prices reach head-exploding heights

Published 10:30 am Wednesday, May 28, 2025

In the running for most-shocking photo of the week, on May 18 one of my fellow members of the West Coast Fisherman group on Facebook posted a snapshot from Seattle of “Fresh Wild King Salmon Fillets $54.99” a pound.

He didn’t say, but it was probably in Pike Place Market, which now caters to tourists and occupants of fancy downtown condos, not the working families it once served. Even so, that’s a heck of a price. And who knows what the first Copper River sockeye will sell for when that season opens today (May 22).

(Someone else posted a photo of a current price board in Ketchican listing whole Dungeness crab for $54.95 and king crab for $92.50 a pound.)

Commenting on behalf of many, a guy said “As much as it sucks, salmon, and fish in general, has gotten to a point that if I don’t go out and catch it myself, I can’t afford to go and buy it — even straight from the dock with no middle man.”

(That’s if you can land one; the brother of a friend of mine recently lost every single salmon he hooked to marauding sea lions.)

A 1900 fisherman

Working 51 days from April 24 to Aug. 6, 1900, Astoria seine fisherman Theodore Kalin caught just shy of two tons of Chinook salmon, 3,911 pounds to be exact. And he counted that as a lousy season, in fact ending up $69.45 in the hole to the Columbia River Packers Association after paying for net and other supplies.

“I send my fish book yesterday. I not call at the Office because I know is nothing coming to me.

“I intend to fish again next summer but I will try to build me bigger boat. Boat I had last summer is too small and that is partly the cause of my poor fishing. I not need twine this winter both my nets is in good condition,” Kalin wrote CRPA on Oct. 2, 1900 from Portland.

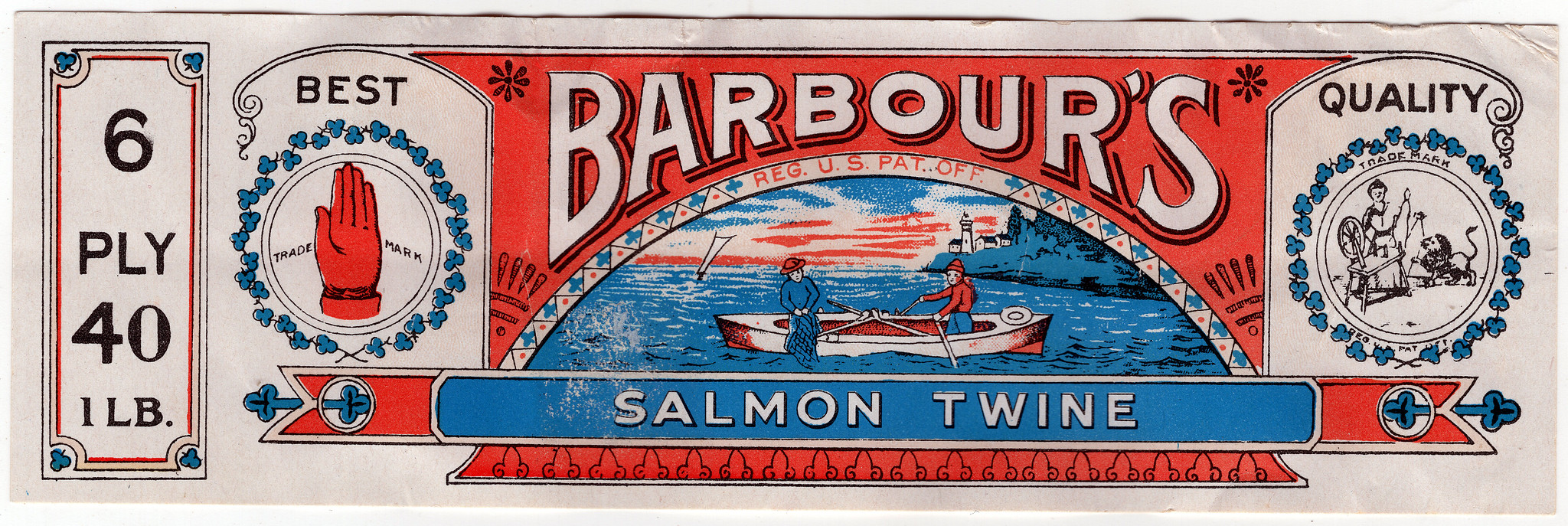

At a time when gillnet boats were built here from readily available materials, imported Irish flax net twine was a huge investment for poor people, with even a good used gillnet going for up to $125 in 1900. Companies like CRPA in effect loaned men twine to make nets in the winter and early spring, and let them charge groceries at the store all summer, in return for an agreement to sell all fish caught to the company at a fixed price.

Early records of the CRPA — which of course went on to become Astoria’s great Bumble Bee Co. — also contain copies of letters to fishermen courting them as if they were star college quarterbacks sought by an NFL expansion team.

Three to five cents a pound

In this day and age, it’s hard to imagine the scale of life in which men worked months for what seems like a pittance.

Fishermen with names like Mateo Stanovich, Antone Radich, Marco Gisdovich, John Inkila, Nels Sankala, Sam Sweeney, Otto Nelson and Andrew Eskola knitted their own nets and sailed the river in search of salmon with horse and purse seines, gillnets and traps.

Depending on the species of salmon and market conditions, turn-of-the-last-century fishermen could expect to be paid three to five cents a pound for good spring Chinook, with a penny bonus for big fish that were more desirable for the lucrative European and fresh-frozen markets.

Salmon was a hot commodity, much more so than now, with Eastern grocers positively clamoring for cases of canned Columbia River fish. All the same, hard cash filtered its way back to Astoria at about the speed of cold tar. This led to a tug-of-war between packing companies and their fishermen, some of whom sold fish on the sly to the competition.

Reporting to CRPA President Sam Elmore in May 1907, Hammond-based foreman Alex Sutton wrote “I have to state that I have had frequent inquiries from our own men (men who confide in me) as to whether I have cash to buy fish. Such men tell me they would like to have a few dollars. They do not like to go to the office, as they are in debt, and to speak of one case, Hansen (Trap), this man last year I have seen him selling fish to the Cold Storage, but now as he is particularly to be seen by me every tide, I think is a check on him, and he cannot sell. This man asked me about money.”

Generational pride

Many living in Astoria, Ilwaco and surrounding communities today wouldn’t be here if their ancestors hadn’t been employed by CRPA/Bumble Bee, Union Fish and other salmon packers.

Their descendants can take great pride in the generally honest and incredibly hard-working men who toiled on the ground floor of what I think can fairly be described as a kind of gold rush, the pursuit of Columbia River salmon.