Skills & Drills: Aspiring fishermen angle for expertise at Washington Sea Grant course

Published 10:19 am Wednesday, April 9, 2025

A Washington Sea Grant initiative convened 25 aspiring and early-career commercial fishermen for a two-day “Skills & Drills” workshop in South Bend.

Under lead instructor and long-time fisherman Robert Maw’s careful watch, participants practiced a range of seafaring basics, including fiberglassing, welding, knot-tying, and net-mending. They also familiarized themselves with navigation protocols and various boats docked at the Port of Willapa Harbor.

The workshop, among other projects, was funded by a nearly $400,000 grant from the Young Fishermen’s Development Program, which awards money from the national Sea Grant office at NOAA to select, regional Sea Grant projects aimed at developing the commercial fishermen of tomorrow.

Trending

Graying of the fleet

The Skills & Drills workshop was part of Washington Sea Grant’s proposal for the fiscal year 2024 grant cycle, and responds directly to a 2022 needs assessment of commercial fisheries in Washington and Oregon.

What Sea Grant staff heard at the time from fishermen up and down the Pacific Northwest coastline was consistent with what the industry has experienced nationwide: the workforce is aging, young deckhands are getting harder to find, and experience and training for new entrants is lacking.

Within the industry, there’s a term for this trend.

“It’s called the ‘graying of the fleet,’” says Jenna Keeton, a fisheries specialist with Washington Sea Grant. “As a concept, it’s about 10 to 15 years old.”

“Historically, it would be the kids of captains that would move up, take on the boat, and become captains, right? So there was this generational handoff,” explains coastal policy specialist Bridget Trosin. “Now we see people who say, ‘Well, I want to go to college,’ or ‘I want to leave and go to the city’… and you know, it’s also not an easy job.”

With the intergenerational transfer of both knowledge and capital interrupted, the industry has increasingly come to rely on adult entrants, or else recruits with less experience and context for the fishing lifestyle. What those who were born into fishing families gained through a childhood of summers spent out on the water, others may have to learn on the job and on the fly. Some catch on quickly. Others are shocked by the grueling conditions and discover — at a captain’s expense — that the work is not for them.

Trending

“If I get the wrong people, it could cost me,” says Maw. “For one of my vessels to come off the water is a $10,000 expense when I get to shore. If I have a deckhand who doesn’t understand that, like, ‘Oh I wanna go home, I miss my girlfriend,’…now I gotta train somebody, I gotta fly somebody up…because you couldn’t hack it.”

Emphasis on resilience

One of the objectives of the Skills & Drills workshop was indeed to impress upon participants the sheer rigor of the job, and to stress the importance of psychological and emotional resilience. An entire classroom session on the second day of the workshop on was devoted to a discussion of these realities.

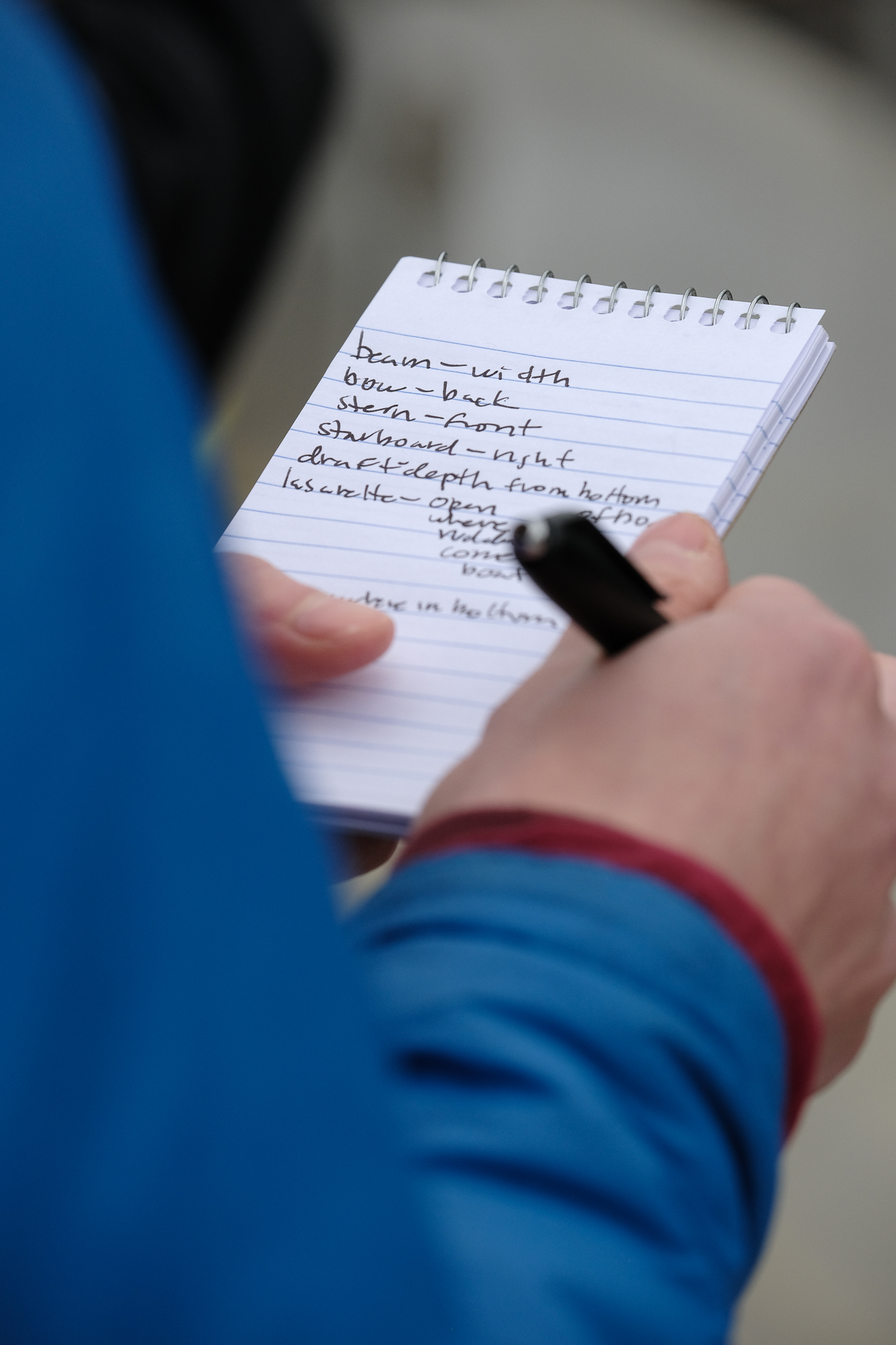

Still, when it comes to figuring out one is made of, there is no substitute for that grueling, first season on the water. And the next best thing an aspiring fisherman can do — both to make him or herself a more attractive candidate and to prepare for that first season — is to do some homework and show up with even a cursory understanding of seafaring terminology and protocols.

Which is where a workshop like Skills & Drills can be meaningful. It won’t turn any of its participants into seasoned fishermen in two days. But it will allow them to board a real fishing boat having at least seen, heard, and performed some of the basics. Keeton wishes she’d had such an opportunity before her own rookie fishing season up in Alaska.

“Going to this would have been insanely helpful. I mean, I had to ask things like… ‘What do you mean by a three-quarter inch socket?’ And they’d have to stop and teach me… and I’d forget because it’s stressful… and that’s, you know, potential fishable time.”

Initiative and willingness

Even more importantly, seeking out and participating in a workshop like Skills & Drills offers inexperienced fishermen an additional opportunity to demonstrate the most valued qualities of all: initiative and a willingness to learn.

“Say you’re Rob [Maw]… and you want to hire people,” says Brandii O’Reagan, a fisheries specialist with Washington Sea Grant and one of the workshop’s organizers. “They don’t necessarily have to be experienced, but they need to know hard work and they need to be trainable, because once you get them up to Alaska, you’re counting on them.”

“You have to show them that you’re willing, and that’s why most people will hire people walking the docks — it shows that you have initiative,” she continues. “But I think classes like this, as they happen, and as fishermen get to know about them, they’re like, ‘Oh, okay, this guy went to this class. I know he can do a weld. I know he’s made a fiberglass patch. I know he has had a net in his hand…and that’s why this is so important, because it’s hard for fishermen to find people. And it’s hard for people to know how to find fishermen.”

Career option

Eighteen-year-old Drew Pearce was one of the workshop’s 25 participants, and almost exactly fits the bill. Unable to justify the expense of tuition after two quarters at Western Washington University, he began considering options that he felt more genuinely excited about, and that would challenge him in the way he was seeking.

“I just want to feel what it feels like to actually go for something like that, you know?” he explains.

And Pearce didn’t even have to walk the docks in order to find a job. All he had to do was strike up a conversation at a mixer hosted by the Working Waterfront Coalition of Whatcom County in Bellingham. One contact led to another, and another, and ultimately to a job set-netting

this summer in Naknek, Alaska, all before he came to the Skills & Drills workshop. And with an attitude like his, it’s easy to see why that worked for him.

“Everyone’s talking about how horrible fishing is, but I’m like, ‘I know it’s gonna be horrible. I’m so pumped. I want to be broken a little bit so I can kind of figure myself out.’”

Riley Yuan is a Murrow News Fellow, part of an innovative state-funded program operated under auspices of Washington State University to reinforce local news around the state. At the Observer, Yuan is focusing on coverage of environmental, natural resource, social and regulatory factors that influence overall community health. His reporting is available for use via Creative Commons with credit.