Saints or Sinners? Characters of Pacific County: ‘Roses in December,’ a teacher recalls pioneer villages

Published 12:51 pm Monday, December 9, 2024

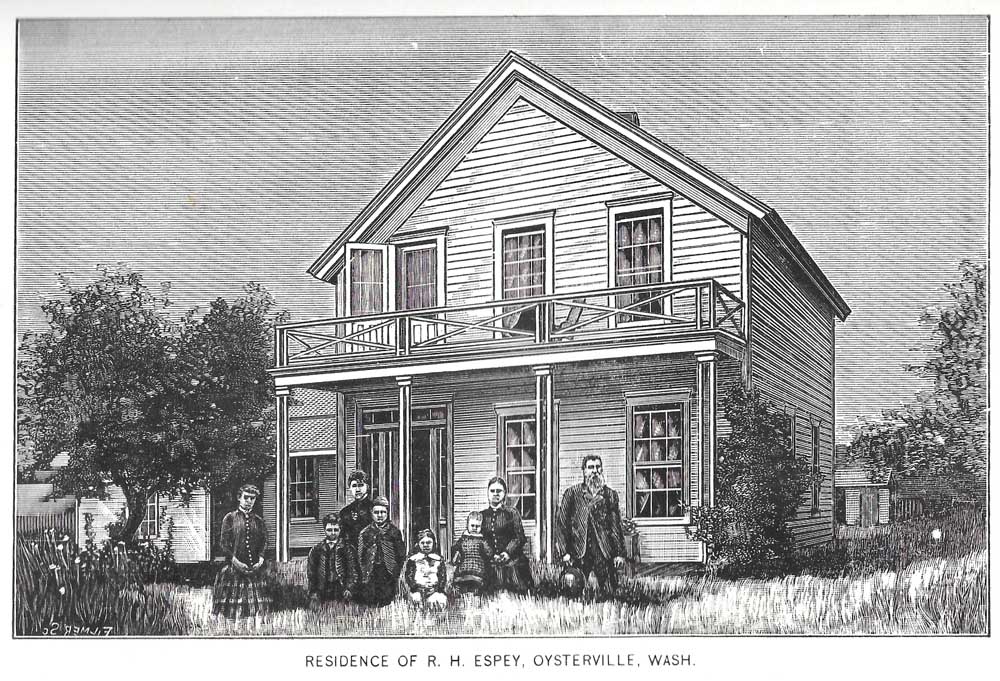

- The portrait of the R.H. Espy home and family shown here is from Volume II of Julian Hawthorne’s “History of Washington,” published in 1893. It depicts the Espy household much as it would have been a few years earlier when Ida Sparks worked there for her room and board while she was attending school in Oysterville.

Ida (Venter) Sparks 1867-1964

Author’s Note: It isn’t often that we get an opportunity to “hear” from one of our early residents, especially a woman, who came here and left within two years, never to return. There must have been hundreds of men and women who did just that, yet they left no mark or record of their time here. So, Ida Sparks’ story intrigued me when I ran across it in the Pacific County Historical Society’s Autumn 1970 Sou’wester. When my great-grandfather’s name popped out at me, I felt I had little choice but to tell at least a part of her remembrances here.

I was born Dec. 18, 1867, the 4th child of a family of fourteen. My parents, William Henderson Sparks and Mary Jane Sale Sparks, in company with my grandparents, Hiram and Margaret Mitchell Sale, came to Missouri in the fall of 1866 — one year after the close of the Civil War. They settled on a farm in the edge of a wood about three miles north of Osceola, in St. Clair County.

The living quarters consisted of two large log rooms and a lean-to kitchen. Each room had a big fireplace. My parents occupied one of these rooms, in which I was born. When I was about four years old, my father bought a small farm on the prairie three miles away to which he moved his family, now numbering six.

I went to school at High Hill for six years, and have fond recollections of my school days there — playing games at recess and noon hours and gathering big bouquets of Johnny-jump-ups, of which the school grounds were thickly carpeted. During these eight years, the family had grown to nine.

Mother and Daddy had a hard time to keep the wolf from our door. Daddy collapsed while fighting a prairie fire and was never a well man again. He had a shoe cobbler’s set of tools and made us shoes out of the tops of old boots given to him. (I was 10 before I had a pair of store shoes.) Mother spun the wool into rolls of yarn and knit stockings until midnight many a time. I learned to knit, too. She wove blankets and linsey for our dresses. I sometimes wound shuttles for the loom and would stand at one end to catch the shuttle when mother was weaving. She later bought brown domestic and colored it with sumac berries and walnut hulls for school dresses. The seam down the back was bias. I complained that it sagged. Daddy said, “You ought to be glad for something to hide your nakedness.”

When I was 20, Father sold our farm, had a sale of all our possessions and moved to Bay Center in Washington Territory — it became a state while we were there. Brother Harrison was a school teacher and had a school out there. Sister Allie (Alice) was married, so that left 11 of us children to go with our parents to that frontier country which was so different from “Old Missou,” but the change was an inspiration to me.

I got work at five dollars a week soon after we landed; so did Rosa, Ella, Ettie and Laura. I worked in the R.H. Espy home for my room and board while I attended high school at Oysterville. I took the teacher’s examination and got a certificate, [and] taught two terms with only five in the district. I also taught 12 Indian children at Bay Center.

I formed some very dear friendships during our stay there, and [received] two proposals of marriage, but refused (they were fine boys); I loved the West, such a lovely climate, energetic people. Bay Center was an oyster shipping center. Father couldn’t adjust himself to the western country with no kind of conveyance but by water, so in a year and a half we came back to Missouri. He insisted on my coming back. The trip on the Columbia River was a delightful one. It called to mind a passage from Bryant’s Thanatopsis: “Where rolls the Oregon and hears no sound save its own dashing.”

“God gave us memories that we might have roses in December.”

(Ida Sparks Venter passed away on March 16, 1964, at the age of 96 years, a short time after writing “This Is My Life” of which the above is an excerpt. She lies buried beside Fred Venter, her husband for 51 years, who died on March 6, 1946.)