Saints or Sinners? Characters of Pacific County: ‘Born story-teller’ inspired by Ocean Park

Published 10:22 am Friday, October 25, 2024

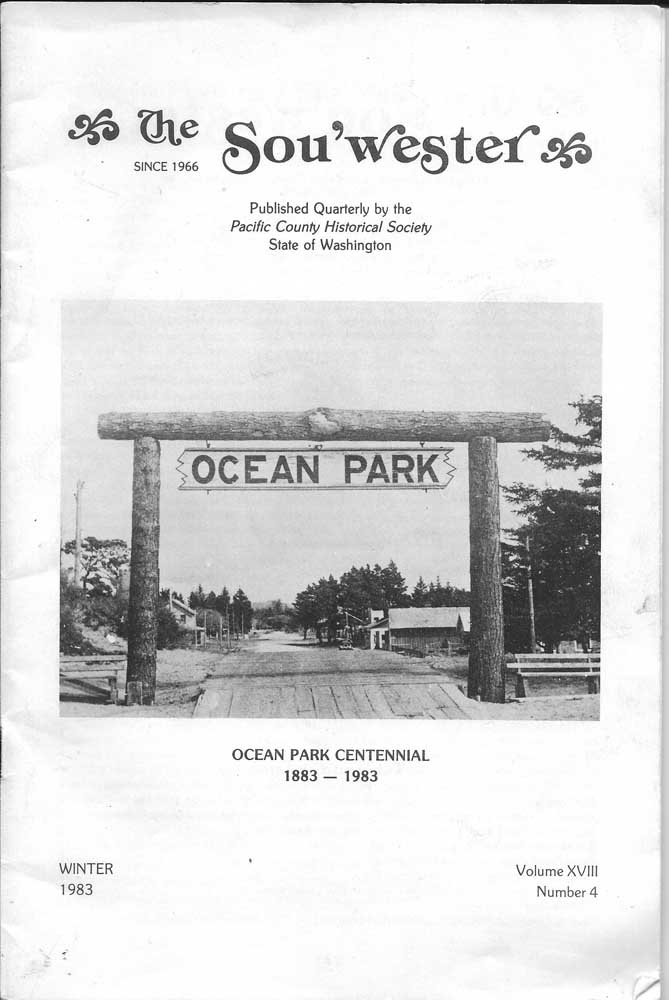

- The Winter 1983 issue of the Sou’wester magazine was devoted to the Ocean Park centennial. The cover photograph featured the old Ocean Park beach approach sign which was dubbed the “Sunset Arch.”

Walker A. “Tommy” Tompkins 1909-1988

Mention Walker Allison Tompkins (always “Tommy” to family and friends) to anyone who spent time on the North Beach Peninsula — especially in the 1920s and ‘30s — and you’re sure to elicit a big smile and probably a most improbable story — though often enough, the stories were absolutely true! Tompkins was “a born story-teller.”

His mother, writer Bertha Allison Tompkins, recalled watching him as he went down the long road through the wheat fields of their farm in Pleasant View, eastern Washington, to pick up the mail. “He would stagger and fall and do all sorts of strange antics. It turned out that he was acting out stories that he was making up.” He was just five and he told her he planned to write story books when he grew up.

True to his word, Tompkins spent nearly a lifetime writing fiction and nonfiction — books, magazines, stories for radio and television. He was an author and a historian with a Western fiction career that had its genesis in the collection of stories he made up in his early childhood while living on that farm.

In his memoirs, he recalled his first trip to the Peninsula, which took place before his eighth birthday while he and his parents were still living in eastern Washington. He described that first trip to the coast as “a hinge-point in my life.” In the years that followed, he would return many times. En route on that first visit, over 100 years ago, he wrote of seeing the Indians harpooning salmon at Celilo Falls and recalled the train pulling into Astoria, where he saw tall-masted sailing ships tied up at the wharves, schooners and windjammers flying flags from the seven seas.

“At Megler, on the Washington side of the river, we left the ferryboat and boarded a little narrow-gauge railroad coach pulled by a teakettle locomotive which puffed its way to Ilwaco and then turned northward up the Peninsula. It was from the windows of such a coach, passing through the town of Seaview, that for the first time in my life I glimpsed the endless expanse of sun-gilded water which was the Pacific Ocean. I cannot put into words the emotional impact that had on a boy who had been born in the dry Yakima Valley.

“When I got off the little narrow-gauge train shortly before my eighth birthday, it was to find a Cape Coddish village [Ocean Park] of weather-beaten cottages and country stores, a village that had started out as a Methodist beach resort in the 1880s. Its people were bucolic, its clamdiggers as colorful as any Maine lobsterman, its community social life clannish and aloof from ‘summer people.’

‘When I got off the little narrow-gauge train shortly before my eighth

birthday, it was to find a Cape Coddish village [Ocean Park] of weather-beaten cottages and country stores, a village that had started out as a Methodist

beach resort in the 1880s.’

“My first impression was an audible one: the constant organ tone bass roar of the ocean surf, invisible behind a high western sand ridge. A cow was grazing in the middle of the main street. Ancient pine trees also grew in the middle of Bay Avenue. Half a mile north of the Ocean Park approach was a landmark dating to 1909, my birth year: the mast and spars of the French barque Alice, jutting out of the surf above the sunken wreck. It was Ocean Park’s trademark until it finally fell in a 1930 storm. Half a mile down the pair of sandy ruts, which were to become the paved state highway down the peninsula, we came to Uncle Guy’s log cabin, The Wreckage.”

In 1920 the family moved to Turlock, California, where Walker continued to develop his writing skills at Turlock Union High School, and as a reporter for the Turlock Union. A few years later, he exhausted himself trying to keep up with his classes and newspaper writing while working two other jobs.

Uncle Guy Allison came to the rescue. ”You love Ocean Park so much,” he wrote, “why not go up and spend a few months recuperating at The Wreckage?”

So, with typewriter, manuscript paper and Roget’s Thesaurus in hand, he headed north. Not too much later, during this stay in Ocean Park, he produced his first published story, “Gold-Plated Handcuffs.”

His sister remembered: “A few days after Walker’s 21st birthday we saw him running toward us waving an envelope. It was a check for his first story in Wild West Weekly…,” said this first acceptance letter from publishers Street and Smith of New York City: “It seems to us that your story “Gold-Plated Handcuffs” is the type of action that we like for Wild West Weekly and we are pleased to purchase it…. We pay one cent per word on acceptance.” His career as a writer was launched! Years later Tompkins said, “For years on end, I ground out Westerns like hamburger.” It was during this period that someone dubbed him “Two-gun Tompkins” — a nickname that stuck to him for the rest of his life.

“With no car, I was forced to walk everywhere, including long hikes on ‘the world’s longest beach.’ I attached myself to the town photographer, Charlie Fitzpatrick, as his camera caddy. I was with Fitz when he took most of today’s historical picture postcards of the lighthouses, the shipwrecks, the tall timber, the weather-beaten stores and homes on the main street, all the vanished landmarks, in a lost era when the surf broke inside Deadman’s Hollow and Beard’s Hollow where today you can drive your car….”

Finding The Wreckage too cold, wet and drafty for winter living, he rented a tiny shack off the main street, next to the post office and Pearson’s Grocery, and converted that into an author’s studio. It was only a stone’s throw from Mrs. Venable’s, where he took his meals. Snugly ensconced in his little shanty, he ground out his western stories and organized a poker club for himself and five local friends — Les Wilson, Bill Winn, John Morehead, Henry Edmonds and Bob Delanoy. They called themselves the “Nitwit Club.”

Tompkins continued to write pulp Westerns while attending the University of Washington. He later moved to New York, where his publishers were located, and while there met and married his first wife, Grace and they moved to California where Tompkins became a features writer for the Santa Barbara News Press. It was there that he became interested in researching local history and is still known as Santa Barbara’s beloved ‘local historian,’ having written 14 local histories before his death in 1988.

He wrote 35 hardcover Westerns and had hundreds of stories and novelettes in novels and magazines. All his life Walker Tompkins felt a special affection for Ocean Park. In his obituary on Nov. 30, 1988, the Chinook Observer noted that he wrote many of his Peninsula friends into his books, such as “C.Q. Ghost Ship,” based on the 1907 wreck of the Solano.