Saints or Sinners? Characters of Pacific County:

Published 9:55 am Friday, August 23, 2024

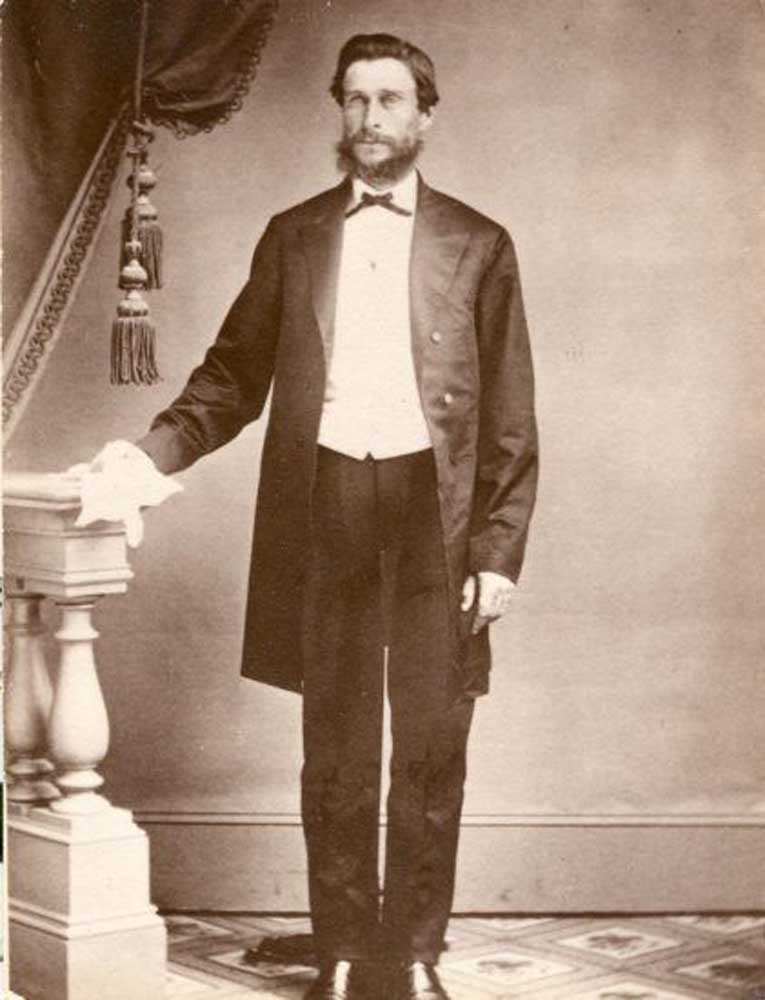

- LEFT: Robert Hamilton Espy’s wedding portrait. RIGHT: Julia Jefferson on her wedding day, Aug. 7, 1870. She is wearing a dress she had made herself.

Robert Hamilton Espy 1826-1918

Most of what I know about my great-grandfather, Robert Hamilton Espy, is from family stories and from a few legal documents on file in Pacific County or State of Washington Archives. Very little is directly from RH himself. He was a man of few words, either written or spoken.

Robert, eighth child and fourth son of Robert Hamilton and Elizabeth Carson Espy, was born Feb. 10, 1826 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. His mother, widowed when he was four, and seeing that his educational opportunities were meager, apprenticed him to a tailor when he was 15. In 1848 Robert bought the remainder of his indenture for a $50 promissory note. He went West with a brother-in-law, who persuaded Robert (who had been a Presbyterian) to convert to the Baptist faith. He also bought Robert a piece of land in the woods near Platteville, Wisconsin.

There, Robert worked in the lead mines and spent the winter of 1849-1850 in the woods learning the logging trade. In the spring he took a lumber raft down the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers to St. Louis, where he was paid off. There he first heard of “Oregon Country” — the Beaulah Land beyond the western mountains.

In the spring of 1852, he engaged to make the trip to California with a “Mr. Whitlock” — young Robert to drive the ox-teams half the time. As the journey progressed, Whitlock (who Robert ever-after referred to as “that old deceiver”) had RH driving the oxen full-time and changed his mind about going to California. They parted company at Oregon City. Robert traveled on to Astoria, found employment in a sawmill, eventually crossing the Columbia River to Pacific County, where he worked for a Mr. Brown getting out pilings for the San Francisco market.

That fall, Robert built a cabin on the Palix River not far from the new settlement of Bruceville on Shoalwater Bay. There, the eight “Bruce Boys” (survivors of the shipwrecked Robert Bruce) had a crew of Indians working with them, piling up oysters to load aboard the next schooner from San Francisco. It did not escape Robert’s notice that the Bruce Boys were earning more in a day than he was in a month — and with a lot less effort. Though they were always ready to share a meal, a tot or two of whiskey and a game of poker, their hospitality ended when Robert began asking about the oyster business.

Returning to his cabin, he talked it over with his friend and neighbor, “Old Klickeas,” who said to meet him the following spring on the west side of the bay. There, Klickeas said, he’d show Robert more oysters than the Bruce Boys ever dreamed of. And so, the plan was made.

Robert spent the winter beachcombing at Point Ellice, getting out of the rain occasionally at Astoria to replenish his supplies and enjoy a game or two of poker. There, he met Isaac Clark, a young man of similar age and background. They even had friends in common “back home!” The main difference between the two: Espy was a Baptist. and Clark, a Methodist — a fact that would not come into play for a good many years.

Keeping Robert’s date with Kickeas, the two young men beached their canoe on April 12, 1854 at the salt marsh in front of what would become Oysterville. After assuring themselves that Old Klickeas had not exaggerated the oyster bounty on the nearby mudflats, Espy and Clark built a 10×12-foot cabin that they shared until Clark’s marriage in 1858 to Lucy Henrietta Briscoe. From that time until his own marriage some 12 years later, Espy continued living alone in the little cabin.

Civic engagement

In addition to his active involvement in the burgeoning oyster trade between Oysterville and San Francisco, Robert Espy quickly became fully engaged in the public affairs of Pacific County. When Oysterville was chosen as the Pacific County seat in 1855, Espy was appointed first justice of the peace. That year, too, he joined the Pacific County Reserve Volunteer Rifle Company, listing himself as “Hamilton Espy” on the company’s roster. Apparently, his Oysterville neighbors looked to him for leadership and elected him major a few years later when they began building a fort north of town. From that time forward, though the fort was abandoned before being completed, RH Espy was respectfully addressed as “Major Espy.”

It was not long before he had accumulated enough money to repay the $50 he owed the tailor for his early release from his apprenticeship. Accordingly, he walked back to Pennsylvania, paid off his promissory note and, by 1861, had returned to his cabin in Oysterville to resume oystering. Soon, however, he left “the boomtown by the bay” once again — this time for a short (and unsuccessful) mining venture in the Blue Mountains. By 1861 he had taken a position as lighthouse keeper at Shoalwater Bay Lighthouse for a year while recovering from a stomach ailment — possibly typhoid.

Back in Oysterville by April 1862, Espy was appointed sheriff of Pacific County, a position he held for six years but finally resigned in 1868 because the county required him to supply his own badge. He felt the county should supply it; it was a “matter of principal.” Or, perhaps, he wished to give more attention to his cattle ranch and his logging interests and the burgeoning oyster business on Shoalwater Bay. In 1867, he formed a partnership with five other oystermen under the name of Espy & Co. at Oysterville and Warren & Co. at San Francisco. The company thrived for the next 30 years.

Other civic duties included his position on the Oysterville School Board. In 1869, he and fellow board member Lewis Loomis traveled to Willamette University in Salem, Oregon to hire a teacher for the 1869-1870 school year. Reportedly, they hired the brightest and the prettiest young teacher of that year’s graduating class, Miss Julia Ann Jefferson. She boarded at the Stevens Hotel while teaching for one full year in the little Oysterville School. Robert courted her on weekends under the watchful eye of her landlady, Mrs. Stevens. Robert and Julia were wed the following summer at her father’s house in Salem. Robert was 44 and Julia, 19. He built her a substantial home where they raised seven children to maturity. Their many descendants still enjoy the big, old house, little changed over the past 150 years except for the addition of running water and electricity, “The Red House.”

In 1871, Major Espy organized the Baptist Church at Oysterville with four members. The growing congregation would meet in the Espy home for 21 years until the Baptist Church was built on land donated by the major and the building paid for with his additional gift of $1,500. He soon purchased the Tom Crellin House across the street from the church to be used as a parsonage.

After Julia’s death in 1902, Major Espy would marry twice more — first to a “fortune seeker,” who the family bought off with a $10,000 note, and finally to “Aunt Kate,” an old friend of the family. She would outlive him by a good many years.

Strict lessons

“Father,” as he was called within the family, was strict with his children and his grandchildren. His son, Cecil was five when a South Bend mob made a midnight raid on Oysterville, murdering two men awaiting trial in the county jail. The next morning, RH took Cecil by the hand and walked him to the jail to view the bodies. “My boy,” he said, “this is what you get for breaking the law.” It was a “lesson” Cecil remembered for all of his long life.

My mother was probably four when she was sent on an errand up the street to the RH house. In order to reach the gate latch, she stood on the bottom railing. RH saw her, thought she was swinging on the gate, and scolded her roundly. Like her Uncle Cecil before her, she never forgot — but the lesson she learned was that he was a mean and grumpy grandfather.

RH rode horseback into his 80s. He was hard of hearing and, in his dotage’ stumped along using two canes. If bored with the Sunday sermon, he was apt to walk out of church early, stumping from his front-row pew back toward the entrance. On one occasion, he stopped at Mrs. Sargant’s pew, where she was suckling her latest infant.

“What number is this?” RH bellowed.

“Eleven, Major,” she answered.

“Good number to stop on! Good number to stop on!” And she did.