Elementary, my dear: If we could fast forward…

Published 9:42 am Monday, April 29, 2024

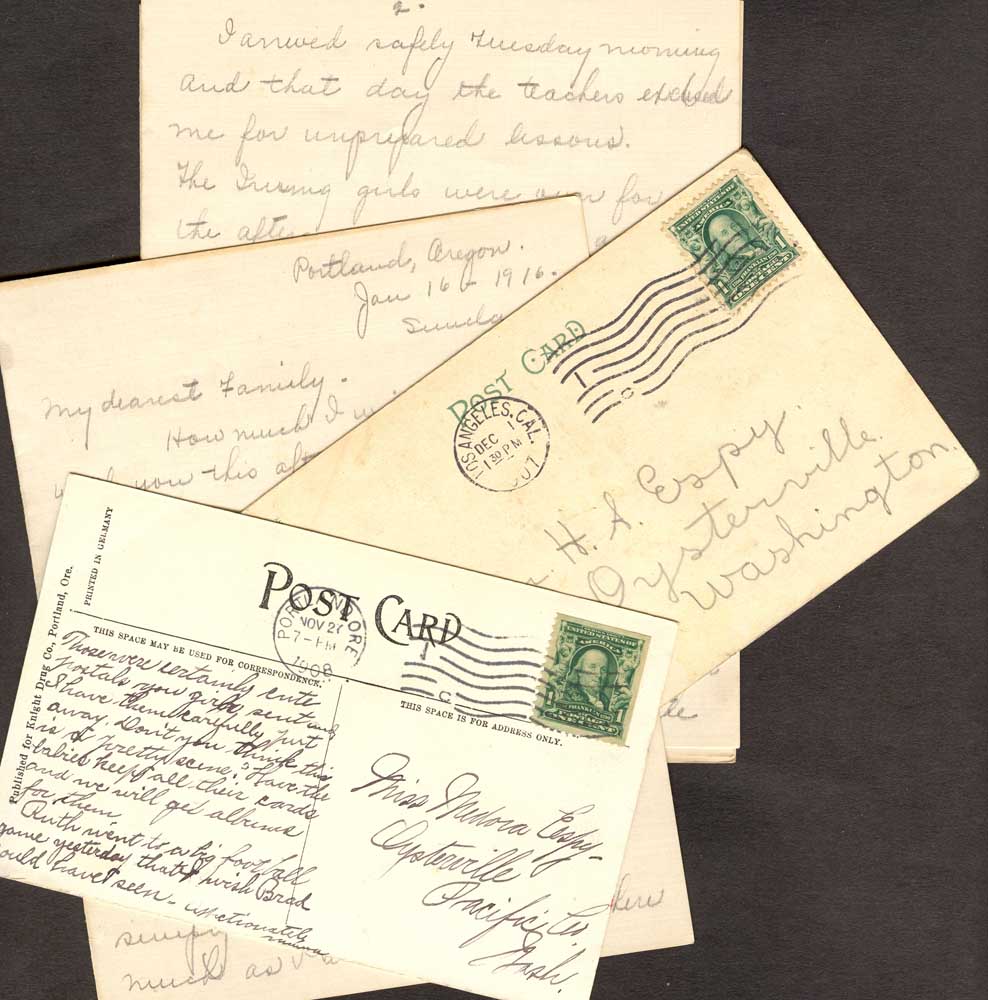

- For generations, the Espys of Oysterville and their forebears have saved correspondence from relatives and friends. Much of it has been utilized as the basis for books written by family members. The collection is now housed at the Washington State Historical Society’s Research Center for use by historians and other researchers.

If humankind can survive its own imperfections for a few more centuries, would any of us have the courage to come back for a visit — assuming, of course, that such a possibility existed? And what would we look for? What questions would we ask?

Trending

I’m pretty sure I’d want to take a look at the most current historic record to see how posterity had viewed the 20th and 21st centuries. I wonder if the information would have any resemblance to what we, today, are actually experiencing.

My fantasy is prompted by a single question that I hear posed more and more frequently — “Why weren’t we taught about that in our history classes in school?” Perhaps it’s because, as Churchill so famously said, “History is written by the victors.” Or perhaps the answer has more to do with that common failing we all seem to have — no two of us ever experiences an identical “reality.”

All of these thoughts have converged lately as I have been researching the lives of prominent (and not-so-prominent) members of our Pacific County community. When I am lucky enough to find comments by two or more of my subject’s contemporaries, seldom do they agree. And, when I am even more fortunate in finding a memoir or letter or article written by the very character I’m interested in, I’m likely to find yet another viewpoint and another set of “facts!”

Trending

Which historical record?

As much as I’d like to correct the historic record — even the record that is within my own purview (like my own, personal story) — I have concluded: impossible! Our history will always be “through. the eyes of the beholder” and, as we know, what I see and understand is different from what your experience may be. I expect that each generation will “correct” their information about the past in line with what they are experiencing in their own “here and now.”

Perhaps, though, we can at least leave our own version of “now” for the future. As I read first-hand accounts of my ancestors — especially in the letters they wrote to loved ones, I am aware of all sorts of subtleties that no history book can convey. Their very vocabulary, the incidents described, even their handwriting tells something of their everyday life — and more and more rapidly that life will differ from our own.

Their very vocabulary, the incidents described, even their handwriting tells something of their everyday life — and more and more rapidly that life will differ from our own.

For those of us who are curious, it’s worth a little research to find some first-hand accounts. Perhaps you’ll run across a stash of old family correspondence as I did — a treasure trove of the details of day-to-day life of the last century. During the years 1913 through 1916, for instance, my mother’s oldest sister was boarding in Portland and attending Portland Academy — there being no way for Oysterville students to get to Ilwaco High School and back. During that time, Medora and her mother kept in touch by writing to one another several times a week.

On Sept. 12, 1913, Mama wrote: I am anxious about your eyes. Take care of them. Always read in a good light and study with the light falling over your left shoulder. More than one person has had to give up school entirely because of abused eyes and what is worse, blindness is often the result. It does not take any more time to take care than it does to suffer the result of carelessness.

That was one of many letters between the two of them that I quoted in my book, “Dear Medora.” I will never forget how appalled I was when a reader asked me “Was your grandmother always so bossy?” When she explained what she was referring to, I snapped (rather ungraciously, I fear) “I don’t call that being bossy! I call it good parenting!”

How much fact? How much perspective?

Belatedly, I realized that I had “brought” to Mama’s remarks the knowledge that she, herself, had always had “weak eyes” and that by the time I knew her well, in the 1940s and ‘50s. she had lost most of her sight and was diagnosed as “legally blind.” My first-hand understanding of her concern for her daughter’s eyes undoubtedly accounted for my knee-jerk reaction to her being termed “bossy.”

So, back we are to “in the eyes of the beholder” and the question of how we can convey our own history to those who come after us. The more I ponder that question, the more I am convinced that each one of us should write a memoir — even if it’s just about one event of significance in our lives. Somehow, we should attempt to leave it for future generations — a sort of window on our “reality” — our snapshot of the here and now,

Maybe, just maybe, if enough of us did that and enough of those bits of our own experience survive, future generations might have a better understanding of us than we do of those who came before us. And maybe future history books will reflect more sides to each “important event” and help give a fuller picture of our lives — at least a picture that goes beyond the names and dates of battles fought and territories won and lost.