Saints or Sinners? Characters of Pacific County: Which is it? Jim Crow or Jim Saules?

Published 9:37 am Sunday, February 25, 2024

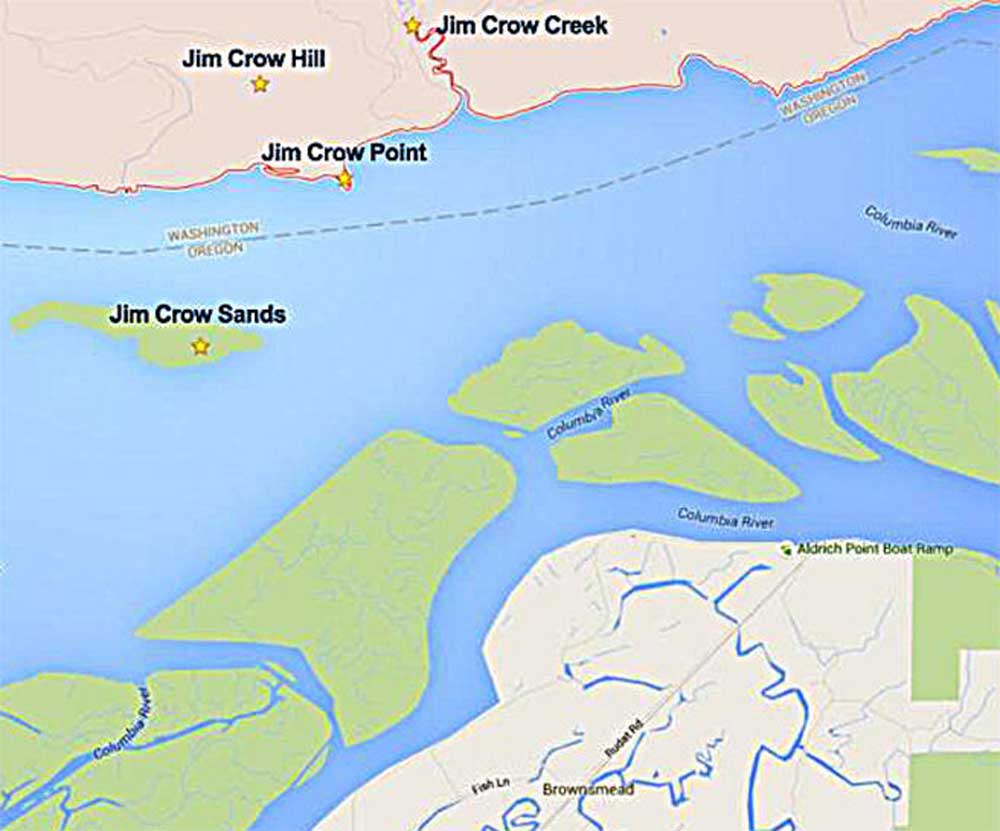

- The three “Jim Crow” place names in Washington shown above — Jim Crow Point, Jim Crow Hill, and Jim Crow Creek — were renamed in 2016 thanks in part to the efforts of Pramila Jayapal, then a state senator and now a member of Congress. (Jim Crow Sands, in the Columbia River, is in Oregon and has not been renamed.) The new names for the Washington designations are Brookfield Point, Beare Hill and Harlows Creek.

James D. Saules 1806? – 1850s

James D. Saules (alternately written “James DeSaules”) arrived on the Columbia River in 1841 as part of the U.S. Exploring Expedition, perhaps better known today as the Charles Wilkes U.S. Naval Expedition. Various accounts of his time in Oregon Territory have identified Saules as a “Black American sailor and musician,” a “Black Peruvian” or a “Black American sailor and musician who arrived in Oregon in 1841 as part of the U.S. Exploring Expedition.”

Saules’ birthplace is unknown, though his birthdate was probably 1806. By the 1830s, he was living in New Haven, Connecticut, and working in the maritime industry, the largest employer of free Black men in the antebellum United States. In 1833, he sailed from New Bedford, Massachusetts as a mate on the whaling bark Winslow, to the offshore whaling grounds of the Pacific Ocean.

By July 1839, Saules had deserted the Winslow and was living in Callao, Peru, where he signed on to serve as ship’s cook on the U.S.S. Peacock, one of the Wilkes Expedition’s six ships. In 1842 the Peacock sailed into the mouth of the Columbia on a survey mission and grounded on a sandspit. The ship was lost, giving its name to Peacock Spit.

Most of the Peacock’s crew were saved by missionaries and nearby Hudson’s Bay Co. fur traders, though several took the opportunity to jump ship. Among those was James Saules who became one of the first non-Indians to settle in the region — at first in the area that is now Astoria. He married a Chinook woman and briefly worked as a bar pilot. In 1842, he started a freight business running a boat between Astoria and Cathlamet and was known for playing the fiddle at social gatherings. There is also some evidence that he got into a bar fight or two during that period of time.

However, by 1843, as Oregon Trail emigrants were arriving in ever-greater numbers, Saules began to confront increasing racist attitudes. While most Anglo-American settlers were anti-slavery, most also believed that Blacks were inherently inferior and would form a troublesome population if allowed to live among Whites. It was not long before the first Black exclusion law was passed in Oregon Territory.

Passed on June 26, 1844, it reiterated a ban on all slavery in Oregon territory, forcing Black and “Mulatto” settlers to leave Oregon Territory within three years (two years for men) or be whipped “no more than 39 times.” Although Oregon Territory at that time extended north to the Canadian border, jurisdiction for the law was limited to the region south of the Columbia River.

Apparently aware of the Columbia River “boundary,” Saules moved to the Cape Disappointment area with his wife. In September 1845, Hudson’s Bay Company Chief Factor Peter Skene Ogden was sent a directive to purchase part of Saules’ land. The deal fell through, however, when two American settlers claimed to be the land’s rightful owners. Though their claim was questionable, they succeeded in removing Saules from the property.

When the U.S.S. Shark sailed into the Columbia on July 18, 1846 to project American power in the region, Saules was hired to pilot the ship up river, but was relieved of his duties when he guided the ship onto a sandbar. A month earlier, Britain had ceded all of Oregon south of the 49th parallel to the U.S. in the Oregon Treaty.

Little is known about the remainder of Saules’ life. Although he was brought before Justice Andrew Hood in Oregon City in December 1846 on charges of causing the death of his wife, he eventually was released from custody. He disappeared from the historical record after 1851, perhaps drowning in the Columbia River in the 1850s as some historians have speculated.

Recently, however, after a 170-year hiatus, Saules was back in the news as a candidate for the replacement name of Jim Crow Point on the banks of the Columbia in Wahkiakum County. (It was even speculated that the “Jim Crow” designation of the Point had been given as a result of Saules’ controversial history on the Columbia.)

The final decision, however, for all three Jim Crow designated landmarks in the area was to change their names to relate to other nearby historic properties thus honoring three early White settlers. Jim Crow Creek, Jim Crow Hill and Jim Crow Point have become Harlows Creek, Beare Hill and Brookfield Point, respectively. James D. Saules seems to have been relegated to obscurity once again.

•••

Most people know “Jim Crow” describes the discriminatory laws that were prevalent before the Civil Rights era. But the name comes from a much older, deeply racist tradition that cast a long shadow over American culture, according to 2016 reporting by the Chinook Observer’s Natalie St. John.

Minstrel show performer Thomas Rice made the name “Jim Crow” famous in the 1830s, Dr. David Pilgrim, president and founder of the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University in Grand Rapids, Michigan, said on April 15. Rice dressed in blackface and gave exaggerated, capering performances of “Negro Ditties,” including “Jump Jim Crow.”