Editor’s Notebook: Captain Disaster: Anniversary calls up epic maritime life

Published 7:08 am Monday, February 19, 2024

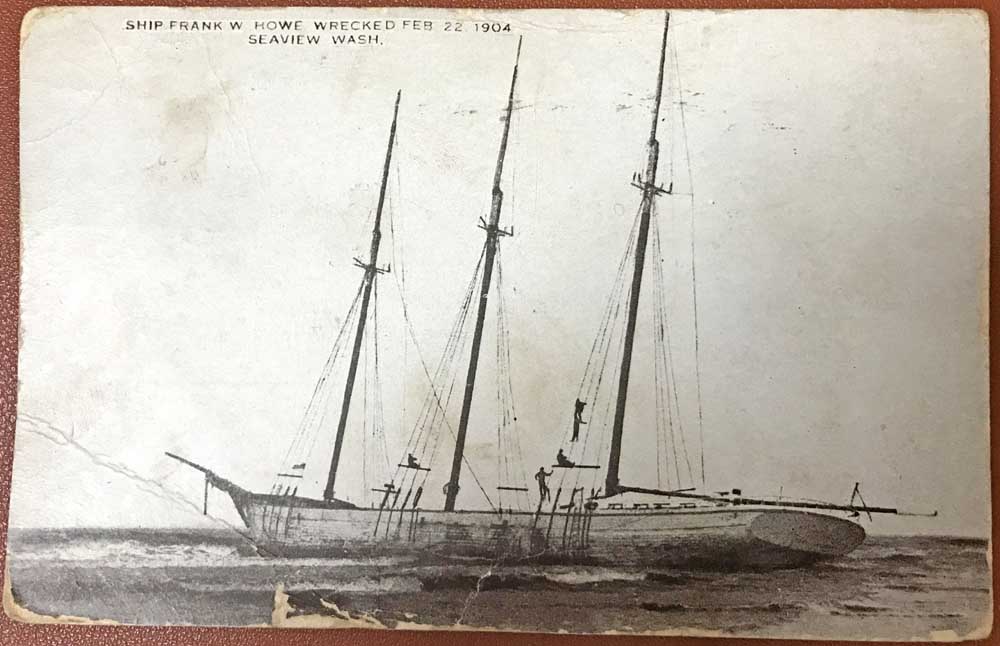

- A postcard mailed in 1911 records the wreck of the Frank W. Howe on the beach at Seaview on Feb. 22, 1904. The crew survived by clinging to the rigging for days in a powerful storm.

Some guys get all the luck. In Capt. Austin Keegan’s case, much of it was bad.

He is perhaps best remembered in Pacific County for the wreck of the Frank W. Howe, a 482-ton three-masted Port Townsend schooner that went aground in Seaview on Feb. 22, 1904 — 120 years ago this week — with a cargo of milled railroad ties. It was his first command.

Shipwrecks in that transitional era when sailing vessels were quickly becoming obsolete were as common as highway crashes are today. Even at the time, the romanticism of the sea carved these disasters a prominent place in local folklore — one we honor today with our long-running “This Nest of Dangers” series by premier nautical historian Nancy Lloyd.

Wealth of records

But it is largely by happenstance that Keegan’s name lives on when those of many of his contemporaries are forgotten. He left behind a fascinating trove of old photos and papers spanning from his birth on Prince Edward Island in 1879 to his peaceful death in San Francisco sometime in the 1960s. I bought this archive in an auction a quarter-century ago and came across it again while cleaning my office.

Self-reported dramatic details of shipwrecks became something of a literary art form, and 25-year-old Keegan did a good job on it:

We sailed from Ballard on Friday, Feb. 12 … all went well until the afternoon of Thursday last … [when] at 1:30 in the afternoon she suddenly filled, apparently as if all her seams had opened. As the water rushed in, the schooner went down by the head and we began to throw off the deckload [of cargo].

There was a terrific southwest gale raging and the waves were running mountains high. One of them broke over the bow and swept the whole length of the schooner, carrying every moveable object overboard and flooding the cabin. Since that moment the craft has been waterlogged and the only thing that kept her afloat was the cargo in the hold …

For nearly four days we have lived in the rigging and on deck without a wink of sleep and almost nothing to eat. The schooner was practically helpless. … The craft labored terribly and we expected every moment that she would go to pieces, but she held out until about 10 o’clock when her back broke clear across under the main hatch.

It was impossible to enter the Columbia and finding that she would weather Cape Disappointment, I turned her north until we drifted past the rocks and then headed for the beach in order to save the lives of the crew. It was a terrible experience and one I shall never forget. …

I cannot speak too highly of the work done by the life savers [the crews from Cape Disappointment and Klipsan Beach Life Saving Stations], as but for them every one of us would have perished.

A report in the March 4, 1904 Chinook Observer notes that Keegan bought the hull and spars for $30 at a salvage auction. The 400,000 feet of rail ties sold for $700.

More ill fortune

He missed out on one notable shipwreck when he next captained the Solano from Aug. 20, 1904 to Sept. 28, 1905. It wasn’t until February 1907, under a different master, that Solano sailed headlong onto the sands near Ocean Park, where it remained a prominent landmark for decades.

But it wasn’t long before disaster again visited Keegan and tens of thousands of others, when the great San Francisco fire began on April 18, 1906, consuming 80% of the city at a cost of 3,000 lives. Keegan and his loved ones weren’t physically injured, but lost much, including his U.S. immigration documents that were eventually replaced after a special administrative process in aid of fire victims.

San Francisco’s ruins may still have been smouldering when in June 1906 Keegan took command of the William Nottingham, a Port Townsend “Cape Horner” bound for Boston with an enormous cargo of over 700 Douglas fir logs. Though Keegan wasn’t named, his adventure was documented in “SOS North Pacific” (1955) by Gordon R. Newell.

The journey got off to an inauspicious start.

“Few seamen were foolish enough to voluntarily sign aboard a fore-and-after for a voyage around the Horn with a cargo of logs. The crimps brought their boatload of human misery alongside and the latest crop from the saloons and sailor’s boarding houses was ready to go to sea again. But one big seaman refused to go. … The sailor’s rusty knife bit four times straight into the captain’s back before that officer sank down, dirtying his sanded quarterdeck with his own blood. The mate’s belaying pin knocked all dreams of liberty from the sailor’s head and the disagreement temporarily reached a stalemate. But the ‘old man’ was only [27] and very strong. A doctor patched up his punctured back and the police took the sailor ashore to the Port Townsend jail, which was preferable to the fo’c’sle of a Cape Horn schooner.”

‘The sailor’s rusty knife bit four times straight into the captain’s back before that officer sank down, dirtying his sanded quarterdeck with his own blood. The mate’s belaying pin knocked all dreams of liberty from the sailor’s head and the disagreement temporarily reached a stalemate.’

‘SOS North Pacific’ by Gordon R. Newell

The shanghaied sailor may have congratulated himself. Keegan’s historic command of the Nottingham from Feb. 21, 1906 to Feb. 24, 1907 featured crashing into a 10-mile-long iceberg off the southern tip of South America.

“Nothing ever survived from a ship sunk like that — there were never the bits of wreckage that drift ashore in kinder latitudes to tell of a ship’s fate — for, on the decks of a windship rounding the Horn, everything was lashed down. This is the way the William Nottingham was meant to go, but she refused to die.”

Just before Christmas 1906, she was picked up by a tug off Sandy Hook, New York, and towed up the coast to Boston, where she unloaded the biggest cargo of lumber ever brought around the Horn. Under a different skipper, the Nottingham returned to the North Pacific and was caught in a fierce gale off the Columbia River, deserted by her crew and left to sink on Oct. 9, 1911. Even then, she survived, and was salvaged and repaired in Astoria before going on to sail for another generation.

Nervous breakdown

Neptune wasn’t done with Keegan. The lead story in the San Francisco Chronicle of Dec. 7, 1909, is about the utter destruction of the steam schooner Majestic near Point Sur, south of Monterrey.

“Captain Keegan, who is on the verge of a nervous collapse at Monterrey, says the storm which drove his vessel ashore was the worst he had ever seen. From early Saturday he had attempted to keep the Majestic’s head off shore about 12 miles. But the heavy southeast gale and a strong westerly current carried him inexorably toward the bleak coast below Point Sur.”

The Majestic was built by J. Dickie & Son of South Bend in 1908 at a cost of $150,000 “and regarded as one of the best lumber carriers on the coast.”

It’s no surprise that four of Keegan’s next five commissions were as mate instead of master, but records indicate he eventually returned to favor. He maintained captain’s credentials until at least 1942 when he was 63.

In a life that clearly deserves to be made into a movie, all wasn’t non-stop excitement. His account book for May 20, 1906 while serving aboard the Nottingham includes this penciled entry worthy of a forlorn teenager: “Capt. Keegan spent a lonesome Sunday because he was sleepy.”

More Coverage

More Coverage

More Coverage

The Keegan name is, unfortunately, also linked with a horrific crime. See tinyurl.com/Keegan-scandal.