‘This Nest of Dangers’: The chaos of shanghaiing

Published 9:04 am Saturday, September 16, 2023

- Ear: Shanghai

“Shanghaiing” was the rowdy art of providing sailors for a wind ship, the souls needed to move the acres of heavy canvas sails by means of pulling on ropes (“lines”). Sounds easy; it was exhausting underpaid labor, months on ends in all climates and moods of the sea.

Trending

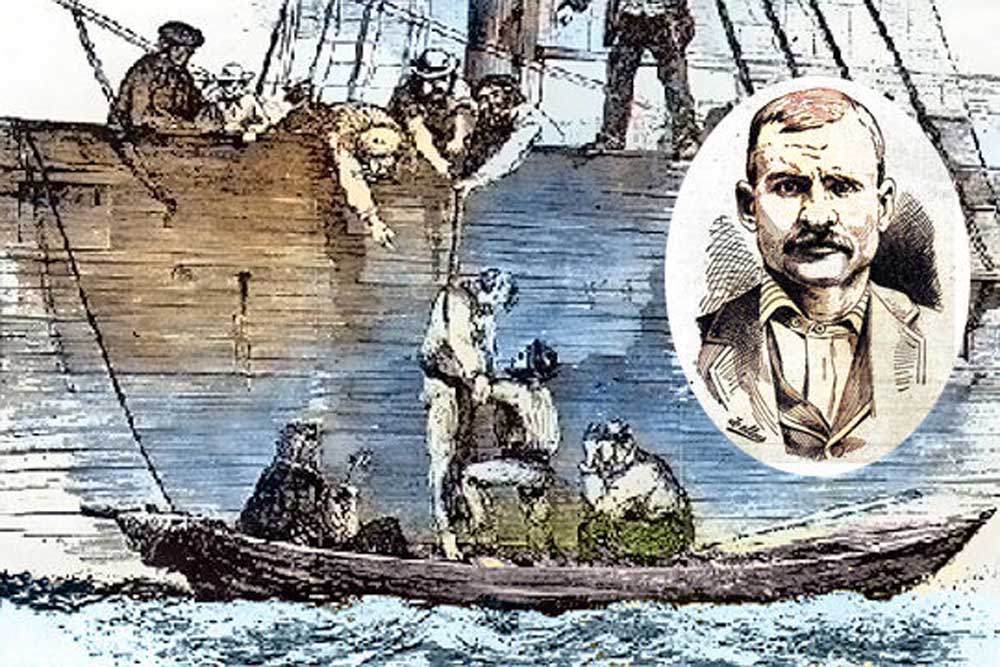

When a sailing ship reached port in our part of the world — Portland, Astoria or San Francisco — those sailors were eager to get off, and they were sitting ducks for deviousness. The shanghaiers, also called “crimps” or “boardinghouse runners,” were delighted to promise incoming sailors the moon (room, board, booze, girls) so as to be able to later “sell” them to another ship captain needing a crew to set sail.

‘Astoria is the very worst place on the face of the globe in this respect. There is no other port in the world where such abuses are carried on under the very eyes of the law.’

The Morning Oregonian, Mar. 13, 1888

Trending

As soon as the incoming ship was unloaded and loaded with another cargo or with ballast, it needed to set sail — time was money — and it needed a full crew to do it.

Some of the former crew had disappeared, and the captain then got to business with the crimps, who found sometimes unsuspecting souls, and got them to sign on board the ship, perhaps without their understanding. The shanghaier might trick, threaten, bully, or batter a prospect, or just generally deceive him or numb him with drink, kidnap him, anything, to get him on board the outbound ship.

The captain paid the “sales price” back from the sailor’s wages to be earned in his months under sail.

Fabulous storytelling

With the discovery of gold just lying in streams in California, men were wild to get west and join in the hunt. They bought passage on whatever vessel they could find, and once they reached San Francisco, they abandoned ship for the gold fields. Pictures of San Francisco’s waterfront in those early days show many dozens of sailing ships crowded at anchor in the harbor, most all of them without a crew.

When a ship needed to leave port, here came the boardinghouse masters, who shanghaied souls to serve aboard those ships. This practice, together with its close connection with the waterfront saloon, brothel, and boardinghouse, made for fabulous storytelling. For the historian, however, it can be hard to winnow fact from fiction.

Portland author Stewart Holbrook, for instance, is famous for his “semi-historical” stories which made it sound as if hundreds were shanghaied each week. However, Portland historian Barney Blalock, who worked on the waterfront for decades, and later did his homework in the museums, concluded, “From all the reading I have done … I would surmise that between one to two hundred people [were] actually shanghaied … in the port cities of Astoria and Portland in the years between 1873 and 1908.”

The practice dwindled as sailing ships grew scarce, steam-powered vessels increased, seamens’ unions grew in strength, and the Panama Canal came to be thereby avoiding the horrid, long, cold trip around Cape Horn. Historian Richard Dillon concluded, “Things slowly improved in Portland, far more slowly than in other havens. The new factors of steam, unionization, legislation, and public opinion finally took effect and the crimps were out.”

Good riddance …

Blood money

“Scattered around the [Portland] Skidroad were also half a dozen joints called sailor’s boardinghouses from which, it was reputed, drunken or drugged men were sent to sea, whether or not they wanted to go, in the lumber schooners and grain ships,” wrote Stewart Holbrook in his 1950s classic book, “The Columbia.”

“In the days of sail,” he continued, “it was the practice to discharge most of a crew on arrival in Portland, to reduce costs while the ship was waiting to load lumber or grain. Then, when she was loaded, her captain engaged a crimp to fill his crew, paying ‘blood money’ for every man supplied. Some sailors, of course, were ready to go. Others, and they might never have been to sea, had to be shanghaied. …”

“On the Pacific Coast, the worst ports [for shanghaiing] after San Francisco and Portland were Astoria, Port Townsend, Tacoma, and San Pedro,” said California historian Richard H. Dillon in his 1961 book, “Shanghaiing Days.”

In the press

A selection of items from Astoria and Portland newspapers illustrate the topic:

“Wednesday evening Constable Ward of Portland, arrested Jack McDonald, a deserter from the ship Harry Morse, and at midnight went on board the Oregon with his prisoner; but not sooner had the nimble son of the sea reached the deck than he was up the rigging, out over the dock on the roof of which he dropped, and started for a saloon for a parting glass, where Ward secured him, and putting him in irons, put him on board the Fleetwood.

“On the way down, Thursday, McDonald stated his determination not to go back to the vessel, and as the boat was pushing off from Cathlamet, having got Ward to take the irons off his wrists under the pretext of necessity, he sprang over the guard and struck out for shore, the boat being about 200 yards out in the stream. … Officers Ward and Burk, after carefully examining the premises, are of the opinion that he sank before swimming 50 feet. …” The Daily Astorian, Nov. 26, 1881.

•••

“The Standard says the cases against [crimps] Lynch and Franklin, who were arraigned in the police court charged with enticing sailors to desert their ship, were dismissed on motion of the State, as the captain of the ship was ready to sail and could not afford time to attend court and prosecute the cases. He paid the amount of costs, amounting to $23, but got his sailors and is headed for the ocean now. …” The Daily Astorian, Jan. 21, 1882.

•••

“An unsuccessful attempt was made to shanghai Wm. T. Ross yesterday afternoon. The police officers went after the man who it is charged made the attempt, but the bird had flown. Ross was taken to the county jail [for protection]. He presented a frightful appearance being beaten and bruised about the head and face. The Daily Astorian, Jan. 5, 1883.

•••

“Portland, Jan. 9 — H. Gibson, a sailor from the British bark Embleton, has made a complaint before Deputy U.S. Commissioner J.O. Bozarth, charging P.J. Paynton, master of the vessel, with grievous bodily injury to one Antoine, a sailor, who died on board that vessel … . The captain was arrested, waived examination, and gave bonds in the sum of $1,000 to appear for trial in Portland.

“The charges against Captain Paynton [are] that on December 27th Antoine was sick with a fever; that the Captain dragged him from his bunk, beat him with a rope’s end, and made him take his trick at the wheel; that the next day he did the same thing; that Antoine dropped at the wheel, and that he and the ship’s carpenter picked him up to carry him to the forecastle; that before they got to the forecastle Antoine was dead.” Sacramento Daily Union, Jan. 10, 1885.

•••

“Mr. James Laidlaw, British vice-consul, … called the attention of the [Portland] board [of trade] to what he denounced … as an outrage, viz., the custom of sailor boarding house keepers in exacting blood-money for sailors furnished [to] out-bound vessels. He referred particularly to the case of the British bark Lucipara …

“Astoria is the very worst place on the face of the globe in this respect. There is no other port in the world where such abuses are carried on under the very eyes of the law. …

“Mr. Laidlaw [said:] — ‘The only remedy I see is the appointment of harbor police to enforce the Oregon laws and send these boarding house keepers to the penitentiary for their misdeeds, but Gov. Pennoyer told me this could not be done.’” The Morning Oregonian, Mar. 13, 1888.

•••

“I have followed the sea for 17 years, generally in the position of steward … I have … not been well [in] over the Bar at Astoria before we have been boarded by boarding house runners and masters. As soon as they step on board the ship the boarding master comes in the cabin, whilst his runners go to the forecastle.

“He brings on board a bottle of ‘K.B.D. [booze],’ and fills up the sailors with this. After making them drunk or nearly so, he tells them about the ‘high wages’ they are paying for sailors on the coast, promising them, if they come on shore to his board house, he will obtain for them a berth in the coasters [which pay higher wages for shorter voyages].

“While the runner is doing this the master is in the cabin asking the captain if any of the men he wishes taken from the ship. … I have seen captains get as much as $100 out of one seaman’s wages.

“When a man is on board a ship, say 12 months, he has quite a little sum due him. … The British shipping act reads that if any seaman shall willingly desert his ship he shall forfeit all that is due him, so when the seaman departs he leaves his wages entirely in the hands of the captain. …

“… I have had this done to me. … I entered the port of San Francisco in the bark Vancouver. Mr. B, commonly called ‘Shanghai B’ came aboard the ship and told me he could get me a position in a ship on the coast [as opposed to overseas] at $60 per month, which was twice the amount that I was then receiving. I foolishly left the ship, leaving behind three months’ wages, and went to his boarding house. I was there three days.

“On the third day he told me he had a fine position for me at $60 per month. I went with him to the shipping office. When I asked, ‘Where is the ship’s destination?’ I was told, ‘Never mind that, you just sign these articles.’ “Of the $60 advance I only received $5. … Not being a fighting man I was glad to take it and say nothing. … John A. Isaacs.” The Morning Oregonian, Mar. 20, 1888.

•••

“Deputy U.S. Marshal Stuart smiled blandly yesterday, when asked in regard to the desertion of eight sailors he brought down to go on board the British ship Strathblane … . ‘I got two of them back and they went aboard the ship voluntarily’ he said. ‘If the ship had only stayed over another day I would have got more of them,’ he added. The Strathblane secured a full crew of 22 men by taking some sailors from another British vessel — the Amnesty it is said.“ The Daily Astorian, Oct. 5, 1890.

•••

“Thomas Raftery, … now a naturalized American citizen, secured release from the British ship Khyber in Portland Saturday, and has had the master, Captain Steel, arrested for kidnapping.

“Raftery claims to have signed the shipping articles while drunk; when on board he asked for his release which was denied and he managed to get a small boy to take a note to a lawyer ashore who instituted habeas corpus proceedings.

“Captain Steel denied that Raftery was not in his right mind when he signed the articles, but the court held otherwise and released Raftery from obligation of serving. The trial of Captain Steel for kidnapping was set for yesterday afternoon.” The Morning Astorian, Apr. 9, 1901.

•••

“Copies of the annual report of British Consul James Laidlaw, as presented to Parliament, have been received here. Mr. Laidlaw’s comment on the crimping business of this port [Portland, Oregon] was mentioned briefly … His report … says: ‘I regret to note an increase in desertions from British vessels at the ports in my district. The percentage in 1901 at this port was 23.45 [sic] from sailing vessels and 1.32 from steamers; in 1903 it was 31.22 and 3.84 respectively. In the Puget Sound ports the situation is no better. Owners and masters will make no stand against the crimps and rely upon the forfeited wages of the crews to recoup them for extra expenses incurred. Rarely is any disposition shown to assist the local authorities in prosecuting infractions of the law, and, in the absence of proper evidence, little is done.” The Morning Oregonian, Sept. 29, 1903.

•••

“When the International Association of Sailing Shipowners got together last spring and established a minimum freight rate which they expected Pacific Coast shippers to pay for transporting wheat to Europe, they decided that Portland should pay a [higher] differential of 1s [shilling] 3d [pence] per ton more than was demanded from Puget Sound ports.

“Individual members of the association, on being pressed for a reason for this differential, stated that it was largely due to the sailor abuses [i. e. shanghaiing] at Portland. This city has been held up by the foreign shipowners and by “London Fairplay,” their official organ, as a port where desertions are more numerous and sailor abuses more flagrant than in any other port on earth. …

“It is an old, old story — so old, in fact, that it is hardly worth mentioning again were it not for the fact that the shipowners have discriminated against Portland in rates because sailors desert here …

“There will never be any permanent reforms in the sailor traffic until shipowners display a little more honesty and consistency than they now exhibit whenever it is to their interest to encourage desertion. Shipowners incite sailors to desert in Portland, and then charge us with a differential of 30 cents per ton because the sailors do what is expected of them, or perhaps what they are forced to do.” Morning Oregonian, Sept. 13, 1904.