Guest column: Why I treasure a book by my father’s favorite writer

Published 9:51 am Wednesday, July 19, 2023

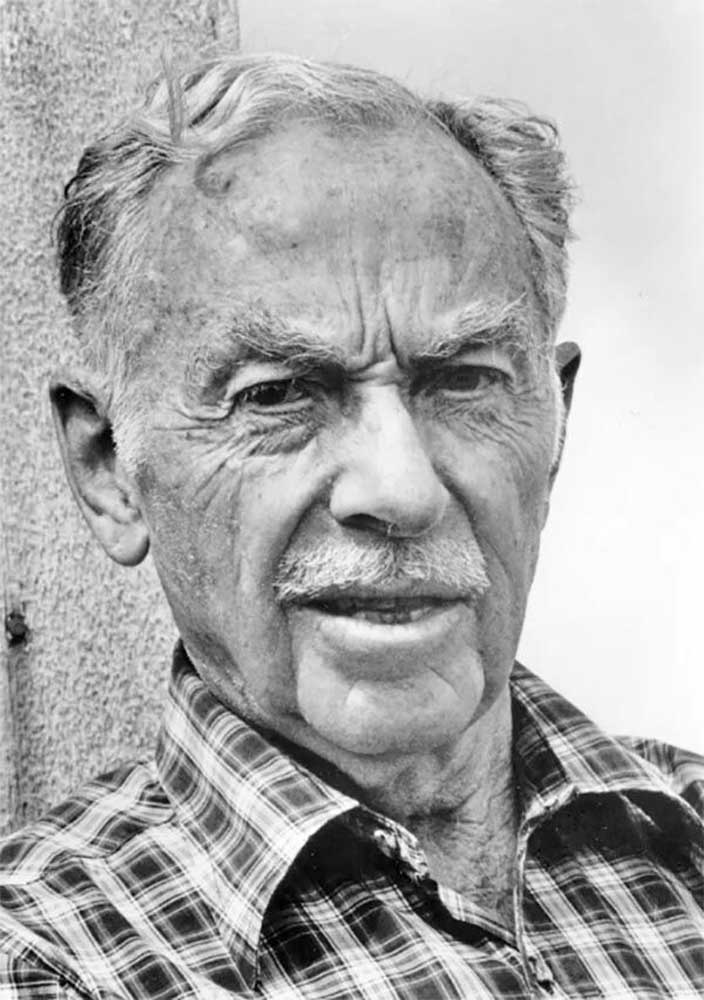

- Author E.B. White was fired from The Seattle Times in 1923 but went on to write books including “One Man’s Meat” and “Charlotte’s Web.”

One hundred years ago, The Seattle Times fired E.B. White. This was in 1923, and White had only been employed a few months. Sixty years later, my dad, John Hinterberger, called him to ask why.

Trending

Dad’s resulting column for the same newspaper poked fun at The Times for its decision. I remember my dad, in those days before computers, talking up the virtue of The Encyclopaedia Britannica. He often relied on our set for research while writing, and I was reminded of this while reading “One Man’s Meat,” White’s collection of essays written at the beginning of World War II, a time of great change.

One passion or idea feeds the creation of a new one. Power lies in the art of comparison, in inviting one neuron to spark the next.

Dad is a devotee of White and especially of “The Elements of Style,” written with William Strunk. He has given me several copies over the years, always extolling White’s gift for clarity and imagination. But today, as we wrestle with the implications of artificial intelligence, it is White’s ability to find new meaning by juxtaposing seemingly unrelated ideas that has me thinking.

White believes “ … the best writing is often done by persons who are snatching the time from something else — from an occupation, or from a profession, or from a jail term — something is either burning them up, as religion, or love, or politics or that is boring them to tears, as prison, or a brokerage house, or an advertising firm.” In other words, one aspect of life informs the other. One passion or idea feeds the creation of a new one. Power lies in the art of comparison, in inviting one neuron to spark the next.

White puts this into practice in “One Man’s Meat.” The essay, “Clear Days,” for example, written for Harper’s in 1938, juxtaposes three personal experiences to reach a larger understanding. White begins by describing a conversation he had with a man while, “sunning on the steps of the store.” They discuss fox hunting. Recalling that conversation spurs White to write about how many folks in town expect him to kill a deer. But White isn’t sure deer hunting is for him. He writes, “ … it’s not that I fear buck fever, it’s that I can’t seem to work up a decent feeling of enmity toward a deer.” But then, just as we think we understand White’s broader point, his thoughts on small-town life and the virtues and excesses of hunting, he adds another dimension: the reroofing of his barn, “all during the days when Mr. Chamberlain, M. Daladier, the Duce, and the Fürher were arranging their horse trade.” Suddenly, the point is larger. Geopolitical relationships are brought to bear. The reader reaches back to earlier sections to find the thread of similarity, of connection.

Near the end of “Clear Days,” White gives a clue to his thesis. “ … I added a cupola to the roof, to hold a vane that would show which way the wind blew.”

He is looking for the direction of change.

White concludes by recounting how, despite his best efforts, lice took hold on his farm. Not in the sheep or the chickens as he had expected, but in the leather seams of his Victrola. “It’s the sort of thing that makes the land so richly exciting: you never know where the enemy is going to strike.” Expect the unexpected, White warns. You don’t know what might go wrong.

This makes me think about AI and Chat GPT, about how they compress vast files of language information, use statistical analysis to link words together and form what appear to be intelligent sentences. It may look like the software is thinking, like the software is writing, but it’s not. The language compiled from other authors is reconstructed into new sequences, new sentences, but not new thoughts. All those statistical regularities unable to fully replicate the human brain’s ability to connect and make meaning out of disparate ideas and experiences.

Some espouse the arrival of AI’s singularity. Suddenly, my paperback copy of “One Man’s Meat,” ruffled with Post-it notes, becomes more precious.

Corporations now have the capacity to compile, compress and dole out most of the words ever written at their command and for their profit. The deluge of information runs modern life. It does not serve, though, to make meaning of that life.

Not like art does.

Dad declared White “one of the century’s most gifted and imaginative writers.” He wasn’t thinking about AI in 1983, wasn’t pondering the existential question of technology’s supremacy: The idea that human thought could be supplanted by machine, the authenticity and joy we experience when reading and writing, lost.

White recalled his time at The Times this way: “I worked there for almost a year. I got the job in September and was fired in June. There was no precipitating incident.” But now, I think, we have some warning.