Drowning at the beach: How, who, why, and what to do about it

Published 1:23 pm Wednesday, July 12, 2023

- Screen Shot 2023-07-13 at 6.48.26 AM.png

LONG BEACH — On the afternoon when Clifford Yarborough IV went for his last swim, his life was full of promise. He had just graduated from a Spanaway high school and had a good job. He had come to Long Beach to take a short vacation with his friends before attending his first term at Pierce College.

Later, tributes would describe him as an accomplished athlete, “a hard-charger” who “always gave 100%.” One account said he swam whenever he could.

When he waded in up to his shoulders on July 28, 2007, and found that he was helpless against the current, he must have been shocked and terrified to learn that neither his athleticism nor his friends could save him.

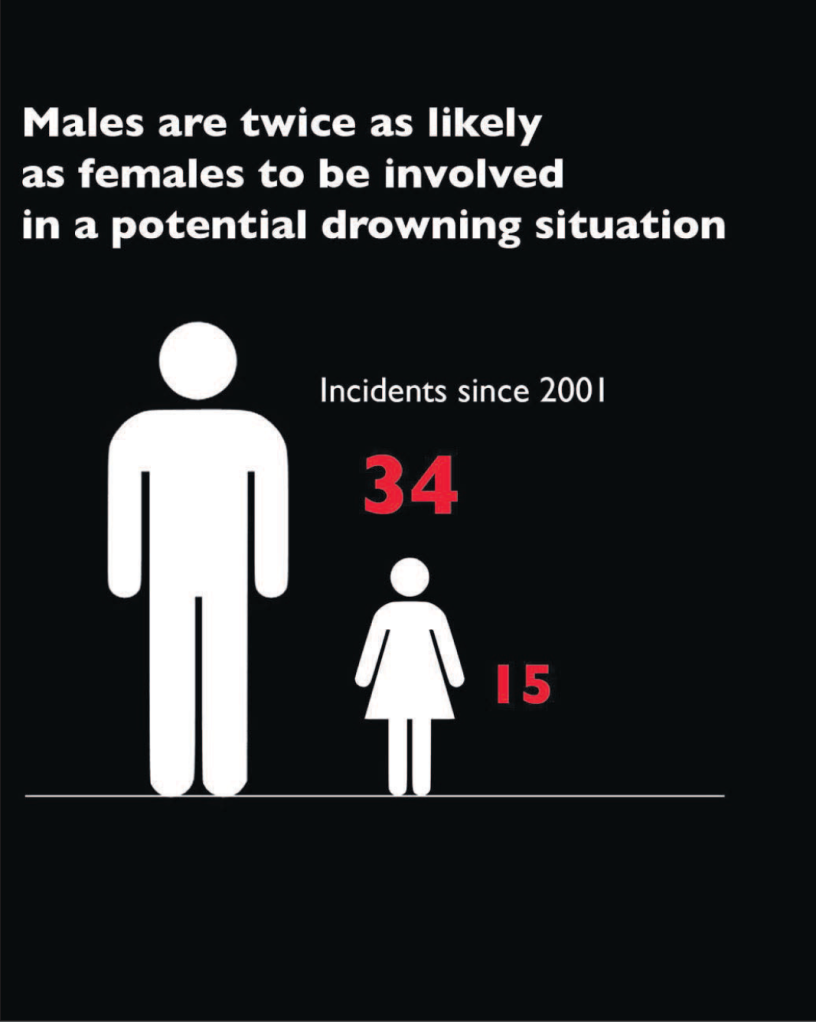

An analysis of surf rescue reports since 2001 shows that for all of his exceptional qualities Yarborough was completely typical as a drowning victim.

Years of deaths and near-misses

With information provided by South Pacific County Technical Rescue and climate and tidal data provided by NOAA, the Chinook Observer created a database of beach rescues [through 2014], hoping to identify the factors that contribute to serious incidents. The results of this ongoing project show that the circumstances are surprisingly consistent. It is possible to say, with a fair degree of accuracy, who is most likely to run into trouble and when.

July and August are when most drownings happen here. With hot inland temperatures certain to draw many to the beach, this is a good time to rerun our award-winning exploration of the hows and whys of fatal drownings. The graphical data here concentrates on drownings from 2001 to 2014. More lives have been lost since then.

Since virtually all people who require rescue on the Peninsula are vacationers, it’s a common misconception that reckless behavior is a factor in beach incidents.

However, the analysis suggests most tourists aren’t irresponsible — they’re uninformed.

There are exceptions, but people generally don’t drown here because they were doing something that was obviously foolish. Instead, the data shows that time and time again seemingly perfect beach conditions are deceptive, dangerous and even deadly to tourists.

Like the majority of people who are rescued from Peninsula waters, Yarborough was young, male and healthy, and did not come from a beach community. Though he felt confident in his physical abilities, he had never really tested them under local conditions. He drowned within the unsupervised beach zone where the majority of swimmers go into the water, and like most distress calls, his came in the afternoon, at the height of summer when the weather was mild, the sky was bright and the water looked harmless. When Yarborough died, the tide measured only 0.4, but the rip current, which has pulled people 100, 200 or even 300 yards out to sea within a half an hour, was totally invisible and viciously strong.

His story is typical in other ways, too. Like other visitors who have been caught off-guard by the current, his friends were unsure how to respond. Later, they told rescuers they didn’t know if they should risk total exhaustion and try to help their friend, or leave him to go for help. At first, they tried to help him back to shore, but eventually they realized they too might die.

Visitors don’t know dangers

A thank-you letter from a survivor of an August 2012 incident in which five people were nearly swept out to sea while wading near the Bolstad beach approach provides valuable insight into how little a typical visitor knows about local water dangers, or how to address them.

When two of the girls in the group went too far, the author of the letter — an adult woman from Tigard, Ore. — tried to help them. She discovered too late that swimming against the current was futile and exhausting. A high schooler and a father joined the rescue effort. They too were overwhelmed. On shore, the other members of the group were apparently unaware that they could call 911 to request a beach rescue.

“I really thought the only option was for us to somehow swim in, and that was not working,” the woman wrote.

She concluded, “Of course I keep racking my brain to think what the proper action would have been in the situation. Run back to the beach to call for help? By then, they may have been gone … I really learned my limit. I guess I knew it, but was fooling myself about my swimming ability, my ability to handle [the] surf.”

Experts cite lifeguards, life jackets as keys to drowning prevention

The summer of 1947 was particularly lethal for tourists on the Peninsula. In July, a mother and a Good Samaritan died trying to rescue a 14-year-old boy from the “treacherous surf.” A man and his young niece perished during another attempted rescue. In August, the body of an “ex-Navy Man” washed up, and a then a minister who loved to swim suddenly sank into the water just as a lifeguard arrived. Another family of swimmers narrowly escaped death when the proprietor of their hotel came to help them all to shore.

Nearly 80 years later, overall drowning rates have declined, but Washington’s drowning rate is still above the national average, according to the Washington State Department of Health. Even with a skilled local team of surf rescue volunteers and other grassroots outreach efforts, tourists still die on Peninsula beaches nearly every year, killed by the same avoidable hazards that have been killing them for decades.

Experts say it doesn’t have to be that way. Beach communities all over the world have saved countless lives through the use of lifeguards, life jacket-loaner programs, flag systems and outreach programs that target high-risk swimmers or dangerous beaches. Research shows that these strategies work. But even after decades of preventable tragedies, Peninsula communities — and the Washington State Park system, which has legal jurisdiction over the beaches — have yet to adopt any unified or evidence-based strategy for reducing beach emergencies. The good news is that there is a growing local interest in finding a solution to the problem. During the last two weeks, locals participated in a town hall to brainstorm solutions, and County Commissioner Steve Rogers hosted a meeting of local emergency response and law enforcement agencies to discuss the problem.

The Chinook Observer asked several experts to explain what works, and what doesn’t. The experts generally agree: Teaching people to recognize risks and take appropriate precautions is more effective than telling them not swim at all. Providing qualified lifeguards and U.S. Coast Guard-approved life jackets are the most effective strategies of all. But experts also highlight a number of other strategies for ensuring that visitors enjoy local beaches safely.

Keep kids afloat, teach them what to do

Derek Van Dyke is a boating safety coordinator for the Washington State Parks System. He helps to coordinate a statewide life jacket-loaner program. Currently, such programs tend to focus on popular boating spots, as well as some lakes and rivers — no such program exists locally. But, there is a growing body of anecdotal evidence that suggests people are becoming more willing — or even eager — to use life jackets while swimming. Currently, Van Dyke’s department is conducting a statewide survey life jacket-wearing attitudes and habits that should be completed by this fall. There are early indications that cultural attitudes are becoming more favorable to life jackets.

He related a story from one field worker, who saw a family of swimmers rush to grab free loaner life jackets before getting in the water.

“Kids like ‘em — they’re fun for little kids, especially in a swimming area, because you can float,” Van Dyke explained. A former teacher, Van Dyke advocates for teaching swimming and water safety to all children.

“That’s the step we have to do — how can we get a water-safety message into out school system?” Van Dyke said. “We could do a lot to prevent this just through education.”

Discuss risks, facilitate safer swimming

As part of the Washington State Drowning Prevention Network, Seattle Children’s Hospital pediatrician Dr. Linda Quan and her colleague, Elizabeth “Tizzy” Bennett promote the motto, “Know the water, know your limits, wear a life jacket.”

Keeping vacationers from swimming while visiting the beach is probably futile, Quan said. A better strategy would be to effectively broadcast the risks of swimming in local water and promote behavior that reduces harm.

“People don’t know the water,” Quan said. “They don’t know that it’s really cold, they don’t know about rip [currents] and they don’t know about ‘sneaker’ waves.” Furthermore, she said, physically able people often simply don’t believe they’re vulnerable to drowning.

According to Quan, one simple, affordable way to reduce local incidents would be to place short, engaging safety messages near the water. Though well-intentioned, Quan said Long Beach’s ubiquitous red “WARNING” signs don’t reach the audience that needs them most.

“Last time I was down there, I couldn’t understand them. I couldn’t read them very well. They were small and they didn’t tell the story,” Quan said.

Instead, she said, hotels and other tourism businesses should advertise by providing life jackets and education materials emblazoned with their logos.

She dismisses the idea that talking about safety hurts the bottom line. In the past, car companies believed discussing the dangers of driving would scare away buyers.

“Volvo showed them otherwise,” Quan said. “It’s very clear that the only option you have is to educate. That’s what you have to do.”

I think you give them information and let them choose whether or not they’re going to go in the water — ‘Here are the hazards. Be aware of the risks.’”

Set and communicate realistic expectations

Station Cape Disappointment Commanding Officer Lt. Scott McGrew is also a surfman, fisherman and an avid surfer and paddleboarder.

He doesn’t think discouraging adults from swimming makes sense in a place where the water is an integral part of the economy and the single biggest recreational attraction.

Instead, he advocates for the lifeguards and the flag systems that are common on better-supervised beaches in California, Florida and Hawaii.

Flags provide a cheap, efficient way to let large numbers of people know about safety hazards, and they get more attention because they’re dynamic, McGrew said.

As a rescuer, McGrew also feels strongly that more widespread availability and use of life jackets would “absolutely” save lives.

“I would say 95 percent of the people would live,” McGrew said. “If you get in a rip, all you have to do is lay down and float and the Coast Guard will come pick you up.” In addition to providing flotation, the bright colors make victims far easier to spot, making rescues more efficient.

But some people, including children and poor swimmers, simply don’t belong in the water here at all, McGrew said, so parents need to set expectations early and often, and be prepared to enforce them. He does not allow his own young daughters to go in the water.

“I have stopped and said, ‘Hey, we’re not in San Diego,’” McGrew said. “Parents should set expectations — this is kite-flying, sandcastle beach, not swimming beach.”

Provide lifeguards, do the right thing

A retired San Diego lifeguard, Chris Brewster is the current president of United States Lifesaving Association and vice-president in the International Lifesaving Federation.

From his perspective, preventing beach deaths is dead-simple.

“Provide life guards, period,” Brewster said in a phone interview.

According to statistics collected from about 120 public lifeguarding agencies across the country, the chances of drowning in an area supervised by lifeguards are about one in 18 million beach visits. They are especially valuable in areas with strong rip currents.

Lifeguards spend much of their time “helping people choose the safest place to swim, helping people avoid particular hazards,” Brewster said.

“Banning swimming only allows people to feel self righteous because they did something you told them not to do,” Brewster said. “If that’s the perspective a community that solicits tourists has, I don’t think that’s going to be very popular over time.”

Brewster has little patience for communities that want to attract tourists, but don’t want to spend money on safety. Providing “responsible levels of public safety” is a basic ethical obligation for those who make their living from tourism, Brewster said.

“It’s an unacceptable attitude, but it’s not unique,” Brewster said. “It’s common to hear, ‘Well there’s so much beach out there we couldn’t possibly afford lifeguards for that entire area, so we wont provide any.’ That’s essentially like saying, ‘Our police department is unable to prevent all crimes, so why don’t we save money and not have cops?’”

People almost always swim near facilities, such as beach access roads, restrooms and parking lots, Brewster said. One practical approach is to patrol only the most populated areas, and actively encourage tourists to use them.

“Swimming in a lifeguarded area is an extraordinarily safe place to swim — if people want to swim in a safe area, what’s wrong with that?” Brewster asked.