El Niño here, but not yet a big climate force in Northwest

Published 5:19 pm Monday, June 12, 2023

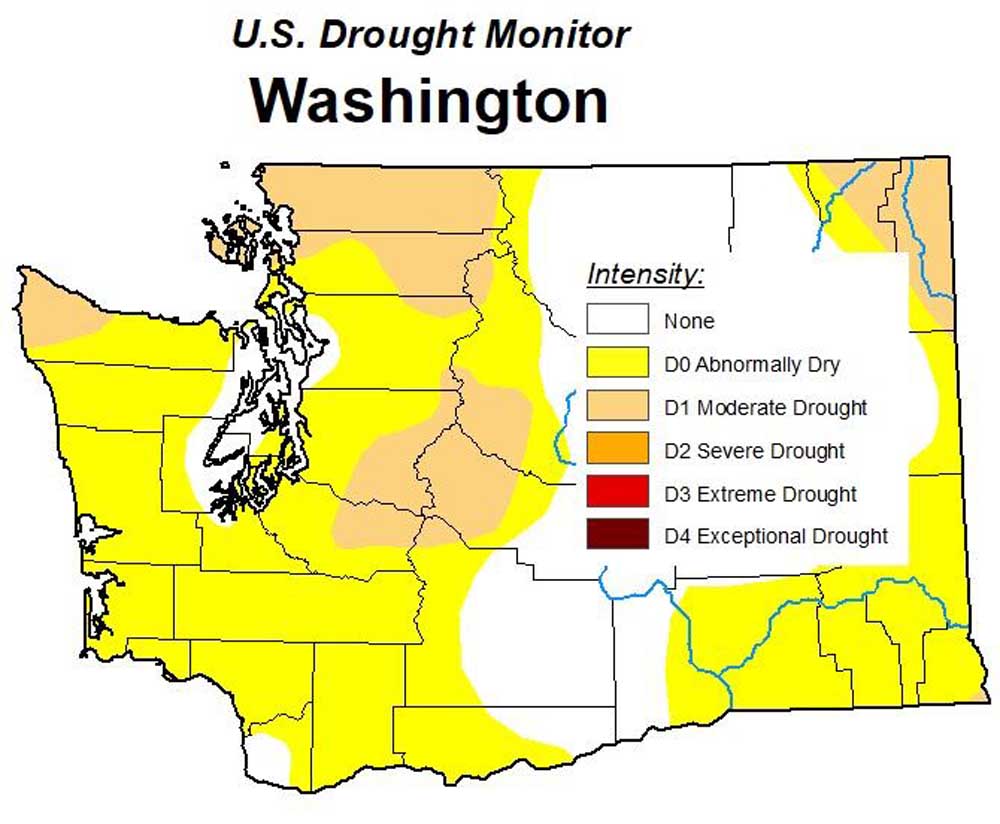

- As of June 13, based on soil conditions 46.3% of Washington was abnormally dry, 14.2% was in moderate drought, and 39.5% was normal.

El Niño didn’t cause Washington’s record heat in May and probably will have a “modest at best” effect on the summer, but may end a streak of large snowpacks, State Climatologist Nick Bond said June 8.

Trending

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced that an El Niño has formed, the first since 2019. El Niño tilts the odds in favor of a warm and dry winter in the Northwest.

It’s still a weak El Niño, but NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center estimated there’s a 56% chance that by late fall it will strengthen into the first strong El Niño since the winter of 2015-16.

For the past three winters, a La Niña, associated with cooler and wetter winters in the northern U.S., has prevailed. The La Niña finally faded in late winter.

Trending

“We’ve benefited from a disproportionate number of La Niñas,” Bond said. “The El Niño is a problem because of what it’s going to do to next year’s snowpack.”

As El Niño took shape, Washington’s average temperature in May was 6.4 degrees above normal, tying 1958 for state’s hottest May, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information.

Oregon and Idaho each had their fifth-warmest Mays on records. Records go back to 1895.

Bond attributed the record month to persistent weather patterns unrelated to the formation of the El Niño. “I don’t think we can really blame El Niño for what we’ve seen so far,” he said.

Bond said he expects the summer to be hot and dry based on global weather models and trends. “Recently our summers have been warm and dry, so there’s reason to think it will stay that way.”

As a rule of thumb, La Niña and El Niño have opposite effects. With an El Niño, California and the Southwest may get cooler weather and more rain in the winter.

Oregon is more likely to have a mild winter during an El Niño, but El Niño’s dividing line between warm and cold winters could fall somewhere in Oregon, State Climatologist Larry O’Neill said.

La Niña’s effects the past three winters have been unpredictable, and that will be the case with El Niño, he said. Ironically, “very strong” El Niños Oregon winters have been unusually wet, he said. “Every El Niño or La Niña is a little bit different.”

El Niño, which triggers changes in the atmosphere, will need time to influence the weather, he said. “In the short term for this summer, I’m not expecting any real impact we can trace back to El Niño.”

Washington’s hot May changed the summer water outlook. Snow held 34.4 million acre-feet of water May 1. By May 18, the snowpack was down to 17.3 million acre-feet, according to the state Department of Ecology.

Much more water than usual ran down the Columbia River in May at The Dalles Dam. Less water than usual will run down in June, according to the Northwest River Forecast Council.

Washington had its 15th driest May since 1895. Drought has started reappearing. The U.S. Drought Monitor reported last week 14% of the state is in moderate drought, up from 5% the week before.

Drought touches 10 of the state’s 39 counties, with trouble spots in the far northwest, far northeast and the center east of the Cascades.