Aerial survey: Willapa among areas hit hardest by 2021 ‘heat dome’

Published 1:56 pm Monday, April 18, 2022

- A severe heat wave last year caused extensive damage to trees around Willapa Bay and the Columbia River estuary.

In summer 2021, from June 26 to 28, an extreme heat wave hit the Pacific Northwest. Known as a “heat dome,” it caused damage to new foliage and buds of several conifer species across at least 84,000 acres in western Washington.

Trending

This heat wave was unprecedented in our region’s history. Temperatures steadily built up to extraordinary all-time high records: 108 degrees Fahrenheit in Seattle, 111 degrees in Naselle, 116 degrees in Portland/Vancouver, 108 degrees in Arlington, and an unbelievable 110 degrees in Quillayute on the western Olympic Peninsula — smashing its previous all-time high by 11 degrees. Ongoing research is connecting the event to human-caused climate change (esd.copernicus.org/preprints/esd-2021-90).

During this event, darker-colored foliage in direct sunlight reached even higher temperatures than the air around it, causing desiccation, or loss of moisture, of foliage exposed to the afternoon sun. Starting almost immediately in early July, branch tips turned red/brown, in some cases looking as if they had been scorched by fire. This heat/sun scorch, also known as needle desiccation in conifers, was especially notable on the southwest and western sides of tree canopies, on south- and west-facing slopes, on younger trees, on trees with more sky exposure, and on trees closer to the coast.

Many different tree species were impacted, with damage most visible on conifers including Douglas fir, western hemlock, western redcedar, and Pacific silver fir. Needles appeared brown or red, and in places branch tips and buds were killed. Damage to hardwoods, mostly appearing as dried leaf edges, was also widespread but less noticeable.

Trending

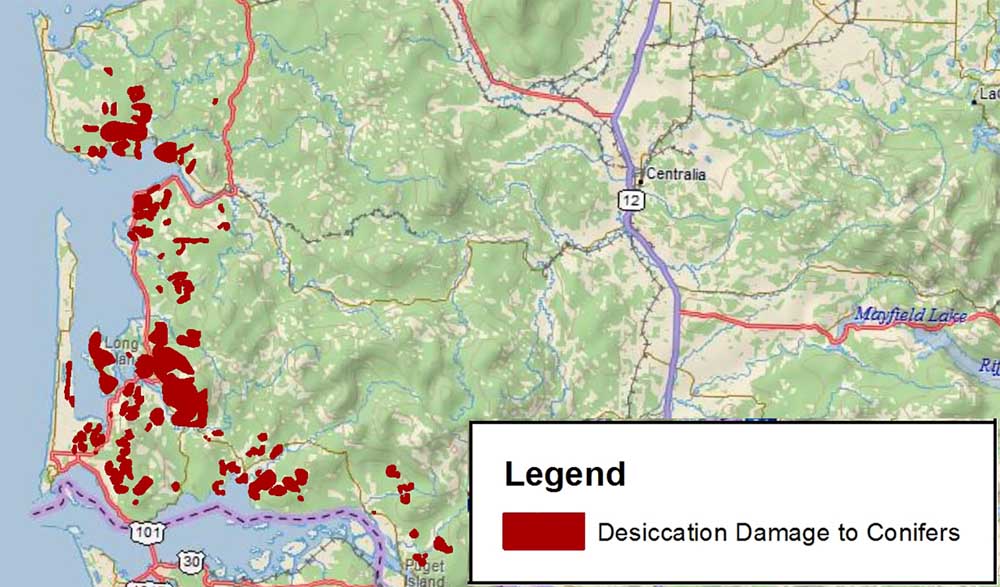

The highest concentrations of damage were on the west side of the Olympic Peninsula, in the Cascade foothills areas of Snohomish, King, and Lewis counties, western Pacific County, Wahkiakum County, and southern Clark and Skamania counties. The extent of damage was likely underestimated by aerial survey because crown discoloration was difficult to see by observers looking to the west and south.

Long-term damage and recovery

The long-term impact of needle desiccation is not well studied, and it is assumed that larger well-established and otherwise healthy trees will be able to recover from this desiccation event.

Over the winter, foliage of impacted western redcedar still remained brown on branch tips. It will be difficult to know whether or not damaged branch tips have died back until the flush of new growth appears in spring. In many of the impacted areas, some western redcedar have already been experiencing top-kill, branch dieback, and foliage loss in recent years, primarily due to ongoing drought impacts. The desiccation damage may contribute to ongoing decline at some of these sites.

Damaged branch tips on Douglas fir and western hemlock were noticeably missing foliage and the majority of buds examined on these branches were killed. The heat was so severe that many new cones were damaged and even thin twigs at branch tips were wilted by desiccation. Health of buds can be assessed by breaking them open and looking for tiny green developing needles inside. Recovery of branches that lost needles but still have healthy buds will be obvious once new foliage expands this spring.

In mature and pole-sized trees, this type of damage is unlikely to lead to whole tree mortality, especially since north and east sides of crowns were mostly undamaged. Any branch tip and top dieback will likely be noticeable for several years until adventitious buds and twig growth from inner branches obscures damage in a few years. In some cases, it’s possible the added stress from this event and recent severe drought years could lead to an increase in attacks by opportunistic insects and pathogens. For young seedlings and saplings, especially in sun exposed plantation sites, the likelihood of mortality from desiccation damage is much higher.

It can be challenging to identify damage from abiotic impacts such as weather events. Without some local knowledge of when and where the event occurred, symptoms can look very similar to foliar disease, defoliating insects, or bark beetles if symptoms are severe enough. The biological pests can usually be ruled out by looking closely for signs of the insects or pathogens themselves, such as fungal fruiting bodies (tiny dark spots on needles), chewing marks, exit holes, webbing, and tunnels or galleries under the bark. Even when you find clear evidence of insects or fungi, it’s always wise to ask why they are attacking the tree. It’s certainly possible that damage from abiotic events like desiccation or drought predisposed the tree to attack, and the two events are linked.

If you have questions about unusual tree damage you’ve observed, feel free to contact your local DNR service forester, extension forester, or forest health specialists at dnr.wa.gov/foresthealth.