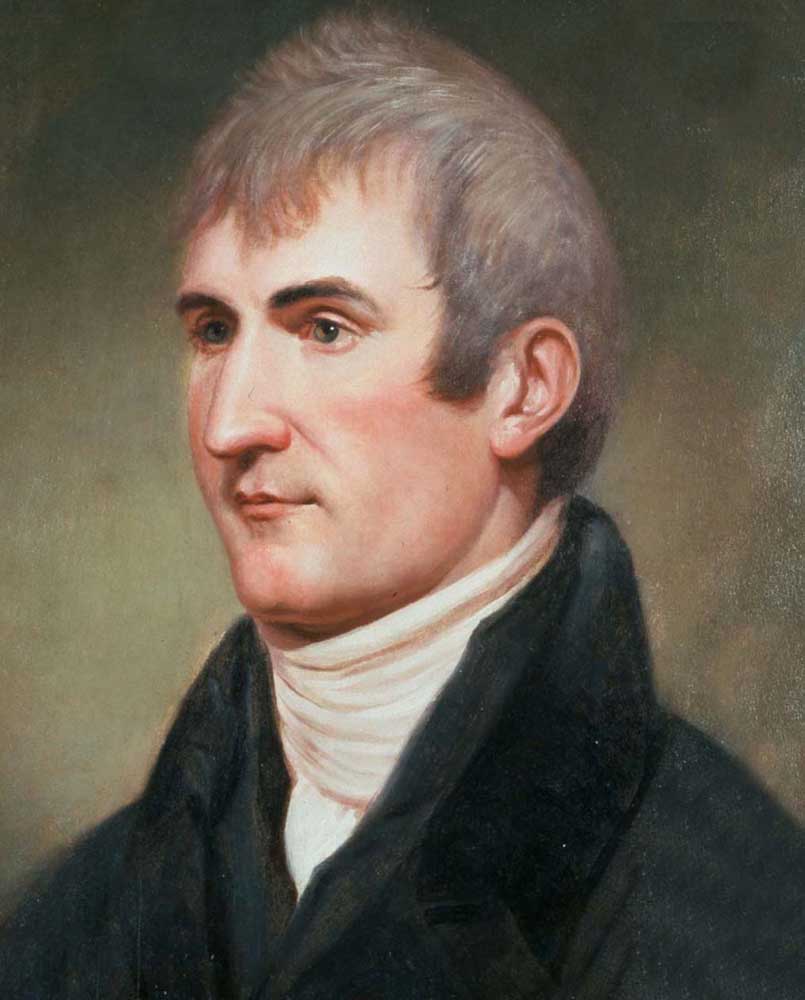

Guest column: Meriwether Lewis: Explorer with ‘Undaunted Courage’

Published 12:58 pm Monday, November 1, 2021

- In early November 1805, Meriwether Lewis was co-captain of the expedition that reached what would become Pacific County.

The 1769 marriage of William Lewis to his distant cousin, Lucy Meriwether, continued a 50-year tradition of marriages between these two landed Virginia families. Born on Aug. 18, 1774, within sight of Jefferson’s Monticello, Meriwether was the second of three children of this union.

Prior to Meriwether’s first birthday, his father became commander of one of the first regiments raised in Virginia. William’s service in the Revolutionary War kept him away from his young family for the next five years. He managed to survive the war only to die of pneumonia during a brief visit home in November 1779. Thus, young Meriwether barely knew his father.

As was the custom of the day, the young widow re-married six months later. She chose Capt. John Marks, a friend of her late husband, and bore him two children. When Meriwether was age 8 or 9, Marks moved his family to Georgia, which was considered “wilderness” compared to life in Virginia. There, Meriwether spent the next three or four years learning frontier skills and relishing in them.

But, Meriwether wanted more knowledge, which he could not get in 18th century Georgia. At age 13 he began his quest for formal education by returning to Virginia. Public schools did not exist in Virginia, either, but this more-developed state did have tutors.

Tutoring was the only means by which youngsters of the day could acquire education; however, demand for tutors far exceeded supply. Finding a tutor took some time even with the help of his family’s long-time friend, Thomas Jefferson. Eventually, Meriwether acquired the tutor he desired: the son of a teacher who had tutored Jefferson during his youth.

Meriwether’s formal education ended four years later with the death of his stepfather. As the oldest son and the inheritor of his father’s considerable estate, it was his turn to support his mother and three younger siblings by taking over management of the Virginia plantation.

Although Meriwether’s studies were minimal by today’s standards, he had achieved the educational level of a well-rounded Virginian. More importantly, he had acquired the knowledge and skills that would serve him well in his future role: explorer extraordinaire.

Meriwether Lewis was certainly itching to explore. When he learned that Jefferson, as secretary of state, was trying to put together an expedition to the Pacific Ocean, he volunteered. Despite his very high opinion of this 18-year-old, Jefferson chose an experienced explorer. [This exploration never took place.]

Young Lewis’ desire to see new lands, to explore and to experience was insatiable. Jefferson wrote “At the age of 20, yielding to the ardor of youth and a passion for more dazzling pursuits, he engaged as a volunteer in the body of militia which were called out by Genl. Washington.”

In 1794 Lewis enlisted as a private in the Virginia volunteer corps and rose to the level of captain in the First Infantry of the regular army. A year into his military career Lewis met a man who was to become his lifelong friend, William Clark.

Just days before he was inaugurated in 1801, Jefferson wrote to Capt. Lewis and invited him to become his private secretary. Shortly thereafter he was released from active duty and moved into the “president’s house” in Washington, D.C.

Jefferson was a widower and Lewis was single. Other than the servants, these two were the only residents of the President’s House for the next two years. Lewis’s quarters were in what would eventually become the East Room. Other than two months with Jefferson at Monticello (summer 1802) Lewis lived there until his expedition duties required him to leave. Long before the explorers started their trek across the continent, Lewis was busy organizing this unique endeavor.

“Of courage undaunted, possessing a firmness & perseverance of purpose which nothing but impossibilities could divert from it’s direction, careful as a father of those committed to his charge, yet steady in the maintenance of order & discipline, intimate with the Indian character, customs & principles, habituated to the hunting life, guarded by exact observation of the vegetables & animals of his own country, against losing time in the description of objects already possessed, honest, disinterested, liberal, of sound understanding and a fidelity to truth so scrupulous that whatever he should report would be as certain as if seen by ourselves, with all these qualifications as if selected and implanted by nature in one body, for this express purpose, I could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprize to him.” Thomas Jefferson

Has a president ever held a subordinate in such high esteem?

Lewis’s duties started 18 months before 51 men and a Newfoundland dog named Seaman, left St. Charles, Missouri in May 1804, to walk, float and ride into history.

First, he became a student again to learn how to make observations and calculations about longitudes and latitudes, flora and fauna, rivers, mountains and plains, local inhabitants and climate, and anything else he might encounter. This took him to Philadelphia to study under the greatest scientific minds of the day, including Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the preeminent American physician.

Jefferson and Lewis stayed up nights making lists of items to take. He gave Lewis a blank check to obtain whatever he thought was needed: How many men? With what skills? How big a boat? How many boats? What designs? What type of rifle? How much powder and lead? What tools? How much dry or salted rations could be carried? What medicines, in what quantity? What scientific instruments? What books? How many fishing hooks? How much salt? What gifts for the Indians? The questions were endless.

These two also came to the conclusion they needed another officer. Only one man came to Lewis’ mind: William Clark.

On July 4, 1803 Lewis began a 10-month journey from Washington, D.C. to St. Charles (near St. Louis) with many detours and stops, arranging the building of a specially built boat as well as purchasing other boats, supplies, equipment, etc. During this time Clark was selecting the first seven men who would make up the corps.

On May 21, 1804, the Corps of Discovery departed St. Charles, Missouri, headed up the Missouri River. Their historical journey ended in St. Louis on Sept. 22, 1806, after many had given them up for dead.

On Feb. 28, 1807 President Jefferson nominated Lewis as governor of the Louisiana Territory, which had been formed while Lewis, Clark and their crew were on their way to the Pacific Ocean. The U.S. Senate quickly confirmed.

On Oct. 11, 1809, during a trip from St. Louis, the territory’s capital, to Washington, D.C., near present-day Memphis, Lewis took his own life. He was 35 years old. Former President Jefferson was deeply saddened to learn of Lewis’ death, but not surprised. He later wrote:

“Governor Lewis had from early life been subject to hypochondriac affections. It was a constitutional disposition in all the nearer branches of the family of his name, & was more immediately inherited by him from his father.”

Using “Undaunted Courage” by Stephen E. Ambrose as her primary source, Oysterville resident Diane Gruber wrote a series of stories about Lewis and Clark for the Peninsula Senior Center newsletter. We’re republishing some of them as our area marks the 216th anniversary of the expedition’s time in the Lower Columbia River, which culminated in their lengthy November 1805 stay at Station Camp near McGowan, which the explorers regarded as fulfilling the chief goal of their mission.