Mourning in hope: Seal River Cemetery

Published 9:23 am Thursday, March 25, 2021

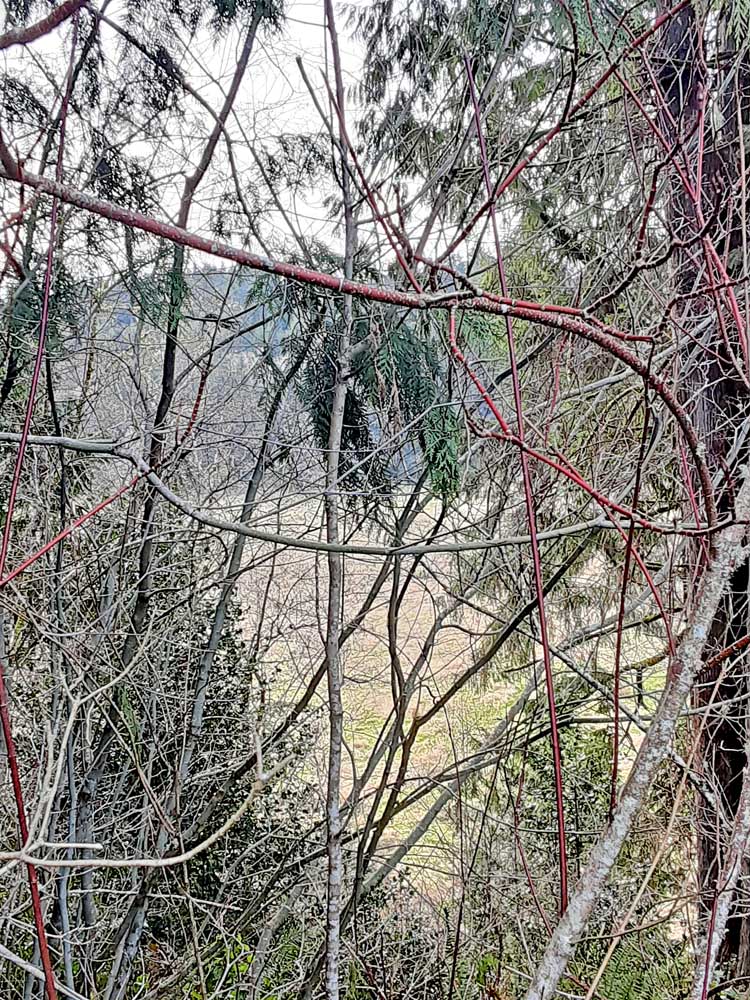

- Tangled branches provide a natural screen along the cemetery’s steep north slope.

There was a certain feeling of disinterment about my journey: the cemetery I was seeking, is itself buried.

Trending

Located just north of State Route 4 in the Deep River area, and just east of little Seal River, it’s a little burying-ground you could pass a hundred times without knowing it’s there. And then, the hundred-and-first, you might notice (but only if you’re westbound), a small green sign: Seal River Cemetery. By this sign I plunged my small car apparently into brush, but struck the narrow gravel road curving up a steep bank, to reveal the improbable panorama of a short-grassed, well-populated little graveyard in the heart of dense Washington rainforest.

The little congregation of Apostolic Lutherans, with their small white church just downriver, needed a churchyard back in the 1880s. The unique topology of this knoll was eminently suitable: sloping steeply down to north, west, east, and south, it offered an essential feature — excellent drainage. (The altitude is less appreciated now: “I was afraid the kids would fall over the edge,” a recent visitor was heard to remark.) Anders and Britta Anet sold the original land, some purchased later from Pete Tervo — surnames that feature prominently in the cemetery’s north section.

1855-1932. Goodness! This man’s life spanned events as far-removed as Florence Nightingale’s Crimean War, the assassination of Lincoln, New York’s first skyscraper, Hitler’s Beerhall Putsch, and the discovery of Pluto.

Trending

The first surnames I saw, set the tone for all the rest — Magnuson, Huttunen, Hattaia. The litany of uncompromising multi-syllable Finnish names went on, broken occasionally by a note of Swedish or Norwegian, rarely a nice pronounceable English one. The earliest inhabitants here were all Seal River Church parishioners, a church which still hosted regular Finnish-language services in the 1970s. But despite my inability to properly render the names or understand the Finnish epitaphs, the numbers on the stones began to speak a universal language, telling their terse, poignant stories. 1855-1932. Goodness! This man’s life spanned events as far-removed as Florence Nightingale’s Crimean War, the assassination of Lincoln, New York’s first skyscraper, Hitler’s Beerhall Putsch, and the discovery of Pluto. Another man’s birth date read 1846: born before the first wagons struck the Oregon Trail. But two identical stones on the west side told a different story: evidently two boys from the same family, one deceased at three, the other nine years later as an infant. A sober reminder that today’s minuscule child mortality in developed countries, is only a phenomenon of the last hundred years.

Energetic Lars Impio and Abram Mustaniemi deforested this land; ironically, 29-year-old Mustaniemi was one of the first to be buried here, after a hunting accident. Today the exuberant coastal flora is trying hard to undo their work. The small Cemetery Board struggles to keep up, organizing annual clean-ups and hiring the grass cut before funerals, though their meetings for this are now curtailed by the covid-19 restrictions. But though dead leaves and branches litter flat stones and salal chokes a rhododendron, I notice signs of dedicated, recent mourners: still-bright fake flowers near graves from within the last decade, small balloons, American flags. There’s also clear evidence this is an active cemetery: two fresh graves in the southeast section.

I ponder the survivors’ grief vicariously, but am suddenly arrested by sorrow of my own: the clean, new headstone of a friend. Some of you will remember Naselle teacher and warm personality, Vivian Agee-Wirkkala. It’s clear: a cemetery isn’t just a peaceful, pretty spot, but the repository of terrible griefs. Many premature deaths are recorded in the numbers on these stones, especially on the older ones. A woman of thirty-eight, the simple legend Mother beneath her name. A World War II sergeant who survived the war by just three years. A boy of eight. How did people cope with such untimely bereavements?

Here’s a clue, lettering around the 1916 stone of a 42-year-old man: Sleep in Jesus. This was overwhelmingly a church cemetery, where the hope of Resurrection pervaded the burial services, death regarded as a temporary sleep. And this hope finds a lively symbol, as I traverse the north section, in hundreds of brilliant daffodils springing out of the drab sod.

I’ll miss out on seeing the very oldest dates of this cemetery. “Many of the early burials were pine boxes and wooden cedar slabs for markers, which have rotted off now,” board member Kari Kandoll relates. But according to the collected burial records, one resident was born as long ago as 1819. I’m lost trying to imagine that world. My own great-great-great grandfather, buried in the southwest section, runs a distant third, born in Finland — like so many of these individuals — in 1836.