New study highlights climate challenges for Chinook salmon

Published 10:25 am Thursday, February 25, 2021

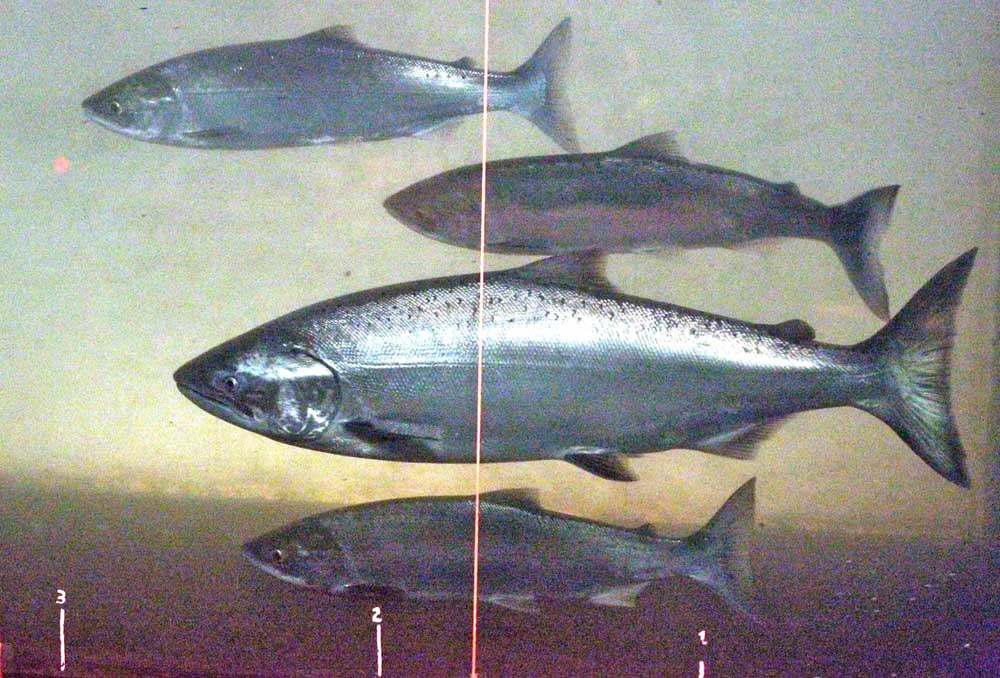

- A Chinook salmon swims with sockeye salmon past the Bonneville Dam fish-counting window on the Columbia River.

The outlook is bleak for wild Chinook salmon in a changing ocean.

Trending

A new study predicts Snake River spring and summer Chinook that migrate through the Columbia River could be nearly extinct by the 2060s without serious interventions as human-caused climate change continues to alter ocean conditions.

The study, led by researchers with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, modeled the survival of eight wild populations of threatened Chinook salmon at all life stages under global climate model projections and found the fish faced especially dire circumstances as sea surface temperatures rise.

Under the model, changes in the ocean presented more of a threat to salmon than what they could confront during the freshwater stage of their lifecycle.

Trending

It was surprising to see how much the ocean stage dominated, scientists said. The ocean is in many ways still a “blue box.” But the study’s authors had already gotten a hint of their predictions in real time.

Though aspects of the work had yet to be finalized, researchers had already completed their model when a mass of warm water formed off the West Coast nearly six years ago.

The so-called “Blob” formed in 2013 and 2014 and persisted through 2015 and 2016. Temperatures inside this warm water anomaly were recorded at nearly 3 degrees C warmer than normal and it set off a chain reaction — a bomb, some scientists said — through the marine ecosystem. Salmon returns over the next few years ran the gamut from “poor” to “concerning.”

“To some extent, we’ve already seen exactly what we predicted,” said Lisa Crozier, a research ecologist with NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center and lead author of the recent study. “It’s frightening.”

The study does not detail what types of conservation and management actions should happen to protect salmon under shifting climate conditions — that is the work that needs to happen next, Crozier said.

But, Richard Zabel, head of the fish ecology division at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and one of the paper’s authors, told The Seattle Times “all alternatives have to be on the table.”

‘Hard choices’

For decades now, there have been efforts to recover salmon with some successes along the way, the researchers write.

“However,” they continue, “there are hard choices where human demands on land and water have come at the cost of wildlife.

“The urgency is greater than ever to identify successful solutions at a large scale and implement known methods for improving survival,” the study states, while also noting, “we have shown that prospects for saving this iconic keystone species in (the United States) are diminishing.”

U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, recently unveiled a plan to breach four dams on the lower Snake River by the end of the next decade in an effort to conserve salmon populations.

But there are many unknowns. As climate change pressures pull certain ecological threads or unfold in ways scientists did not expect, it isn’t always clear what else starts to unravel or what knits back together in new ways.

Crozier is part of a push now to delve into models that will look across marine species and their life cycles to start to build an understanding of intersecting relationships between predators and prey and how they all might shift in different ways with climate change.

Despite all the terrible things that have come with the coronavirus pandemic, Crozier believes the temporarily lower carbon footprint that came with decreased travel may offer an important opportunity.

Normally, researchers look to quantify human impact by comparing differences between years, something that is hard to isolate for climate change research as human activities rush forward. With the pandemic, air traffic slowed and there were fewer vehicles on the road as work and school moved into the home.

“We were quieter for a while,” Crozier said, “and that’s a big deal for the ocean.”

‘Faith in the fish’

While the news is dire for salmon under the model she recently had a hand in completing, Crozier is not without hope. The situation is not a simple black and white, she said.

“It’s not really a good situation, but I don’t think they’ll go completely extinct,” Crozier said. “I think they will change their behavior. They’ll modify things. That’s what salmon do, they change.”

While salmon are resilient and adaptable, it is on humans to watch for these responses and “give nature the flexibility it needs,” she said.

“I have a lot of faith in the fish,” she added. “I have a lot of faith that a lot of people care about these fish and I have a lot of faith that people will see the shared benefits.”

Then there is everything we don’t know, things scientists cannot predict about salmon and how climate change alters their habits and relationships with prey and predators. There could be an “ecological surprise,” the study states, “that will reverse the historical relationship between (sea surface temperature) and salmon survival.”

“I hope for the unexpected,” Crozier said.