Shad fishing in Washington

Published 10:24 am Tuesday, April 11, 2017

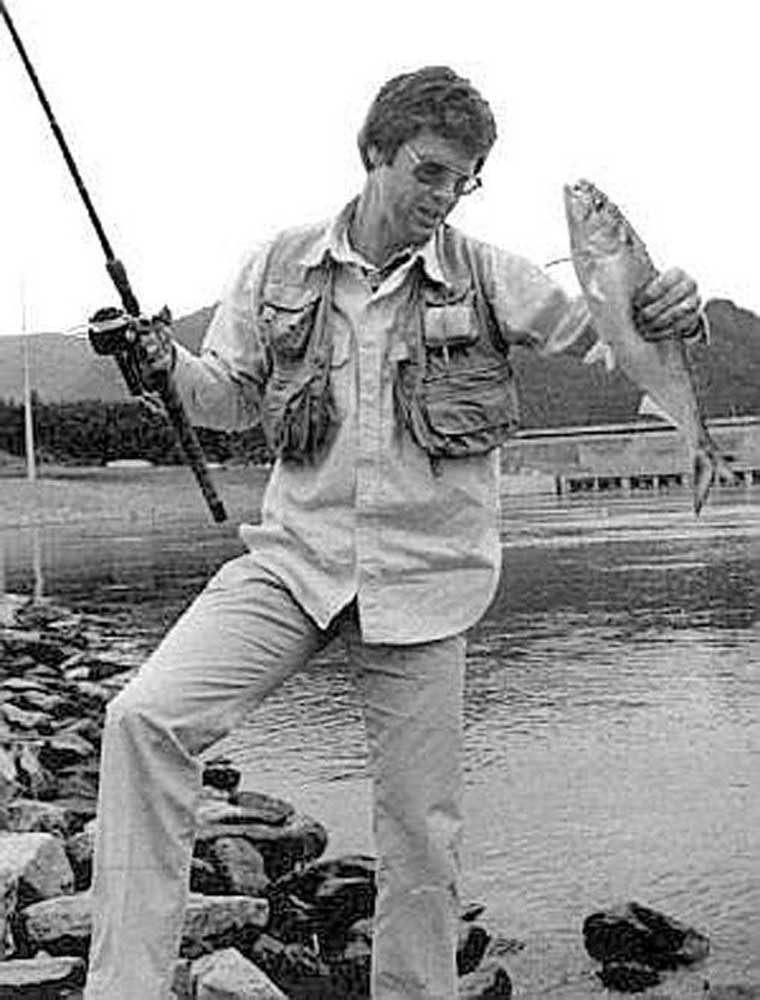

- A Washington fisherman lands a shad, a non-native fish that has established a large spring run on the Columbia River.

What’s so great about shad?

Trending

You might call shad the lottery fish of Washington. When you’re talking shad, you’re talking big numbers. But there’s one major difference — shad are a lot easier to come by than those million-dollar lottery payoffs. Hit the Columbia River below Bonneville Dam from late May through June and you’re likely to hook into a million-count shad jackpot.

You might also think of shad as the piscatorial Rodney Dangerfield — they don’t get nearly the respect they deserve. The word is slowly getting out, though, that shad fishing is great sport. These stout battlers don’t give up easily, and often put on a flashy aerial battle. Couple their strong fight with a tender mouth, and landing half of the shad you hook can be an accomplishment.

Add to this the fact that there is an abundance of this largest member of the herring family. The estimated size of the shad run, based on fish passage counts at Bonneville and The Dalles dams, first topped 1 million fish in 1978, and has stayed well above that figure ever since.

Trending

Usually called just “shad” on the West Coast, the correct common name for this introduced species is American shad. The scientific name is Alosa sapidissima, from the Saxon word allis (an old name for European shad) and the Latin word sapidissima (most delicious).

American shad are the only anadromous or ocean-going shad on the West Coast. Native West Coast members of this family (Clupeidae) include Pacific herring and Pacific sardines.

On the East Coast, American shad reportedly grow to 30 inches and more than 10 pounds. Average size here is 17 to 19 inches and three to four pounds. Females run an inch or two longer than males, and are correspondingly heavier.

The back is metallic-blue to greenish, shading through white to silvery on the belly. A row or rows of dark spots decreases in size toward the tail. These spots are not always visible, but show up when the fish are scaled. A very distinctive characteristic is the saw-like serrated edge along the midline of the belly.

Like salmon and steelhead, shad are anadromous. They enter freshwater rivers in the spring to spawn. Unlike Pacific salmon, they do not necessarily die after spawning. Many shad continue to spawn annually.

Spawning takes place at water temperatures between 50 and 60 F, primarily at night, with the eggs being extruded in small numbers near the surface. The average female bears more than 50,000 eggs, sometimes as many as several hundred thousand.

After fertilization, the eggs slowly sink as they drift downstream, finally becoming lodged in crevices or on aquatic vegetation. After the fry hatch in five to 10 days, they gradually work their way downstream, usually spending their first summer of life in the river. Males usually mature at three years of age, females at four.

Shad have a colorful history. Long before being imported to the Pacific side of the country, they were getting a name for themselves. As far back as the Revolutionary War they helped the cause of the future U.S. After suffering through a tough winter, General Washington’s undernourished troops at Valley Forge welcomed the bounty of a large shad run on the Delaware River. The volunteers filled out their diet with smoked shad.

Another shad tale dates back to the early days of our country. One Pennsylvania town had lost most of its men in battle. After that, the first net throw of the shad season was donated to the bereaved families. It is still known there as the “widow’s haul.”

Then, there were some Civil War military men who enjoyed their shad too — but probably to the detriment of their cause. As the story goes, Confederate General George E. Pickett and all of his senior officers missed the last battle of the Civil War on April 1, 1865 at FiveForks, Virginia. Two weeks before the Appomattox Courthouse surrender. The officers reportedly missed this fray because they had accepted an invitation to dinner — a shad bake.

The historic story of interest to Washington anglers, however, could be called the “shad shuffle.” No less than the gentleman who is considered “the Father of Fish Culture in the United States,” Seth Green of Rochester, New York, personally escorted the first shad as they came to the West Coast.

California fish commissioners, who recognized the value of shad as a food fish and must have been especially alert to the fact that Easterners enjoyed shad roe as a gourmet delicacy, wrote the man who had become an internationally-known fish culturist. Green responded to the commissioners’ request and decided to try bringing the initial Pacific shad across the continent via railroad.

The challenging, seven-day journey began on June 19, 1871 at 6 a.m., when Green loaded “12,000 young shad that had been hatched the night before” into four eight-gallon milk cans.

The escort’s memoirs report that he deposited the first shad at 10 p.m. on June 26, 1871, in the Sacramento River. His records also indicate that “about 10,000 (were transplanted) in good order.”

The transplanted shad thrived! As a 1986 American Fisheries Society paper describes it, “The American shad population exploded … American shad were sold in San Francisco markets by 1879, only eight years after being introduced.”

Shad soon found that they liked more northerly waters too. Even before shad fry were deliberately planted in the Columbia River drainage system in 1885, some of the original immigrant population strayed north from California and homed in on the Columbia River. Shad may have been caught as early as 1876, and U.S. Fish Commissioner records document that mature shad were taken from the Columbia in 1880.

Columbia River dams appear to have played a contributing role in the current large shad populations. For the first 23 years counting was done, starting in 1938 after the completion of Bonneville Dam, total estimated shad counts at Bonneville Dam averaged about 136,600 a year. (Minimum run size based on fish ladder counts plus commercial and sport catch.) But when The Dalles Dam was completed in 1956, its fish ladders removed the upstream barrier created by Celilo Falls. Shad moved up into the Snake River, and their numbers really started to climb.

For the next 18 years (1961-1978), an estimated average of 475,900 shad entered the river. In 1978, the first 1 million shad run was recorded. Average estimated run size 1979 through 1993 was 1,597,000 shad, topped by 3,253,000 in 1990. Factor in that the average commercial catch for 1990 through 1993 was less than 125,000 fish, and you have lots of shad available for sports anglers.

The first popular fishing spot that shad reach in Washington is in Camas Slough, about 25 miles downstream from Bonneville Dam, and in nearby areas of the mainstem Columbia (particularly at the upper end of Lady Island). Fishing may be good here as early as mid-May. Lots of river is available between the mouth of the Columbia and Camas-Washougal, and a few shad fisheries may be developing in this 120 miles stretch.

The best fishing, though, is usually just below Bonneville Dam, and takes place in the first few weeks of June. In late June the run moves up through the Dalles and John Day Dam areas. By the second week of July, most of the fish will probably have taken their turn into the Snake River and be in the Ice Harbor Dam area.

Water temperature and river level can affect the run timing. A high runoff from large snowpack, or increased water levels from flushing salmonid smolts downstream, can slow the run down a week or two. A low, clear river might bring them in earlier. The best way to gauge the run is to watch the sports section of most Columbia River-area newspapers for fish ladder counts at the dams.

As of April 9, no shad had returned to the Columbia in 2017. In 2016, 1.77 million shad were counted passing Bonneville dam. Other recent totals were 1.81 million in 2015 and 2.6 million in 2014.

Learn about fishing for shad and how to prepare them at wdfw.wa.gov/fishing/shad.