Sturgeon survive fishhooks to start spawning around age 18

Published 10:38 am Friday, August 28, 2015

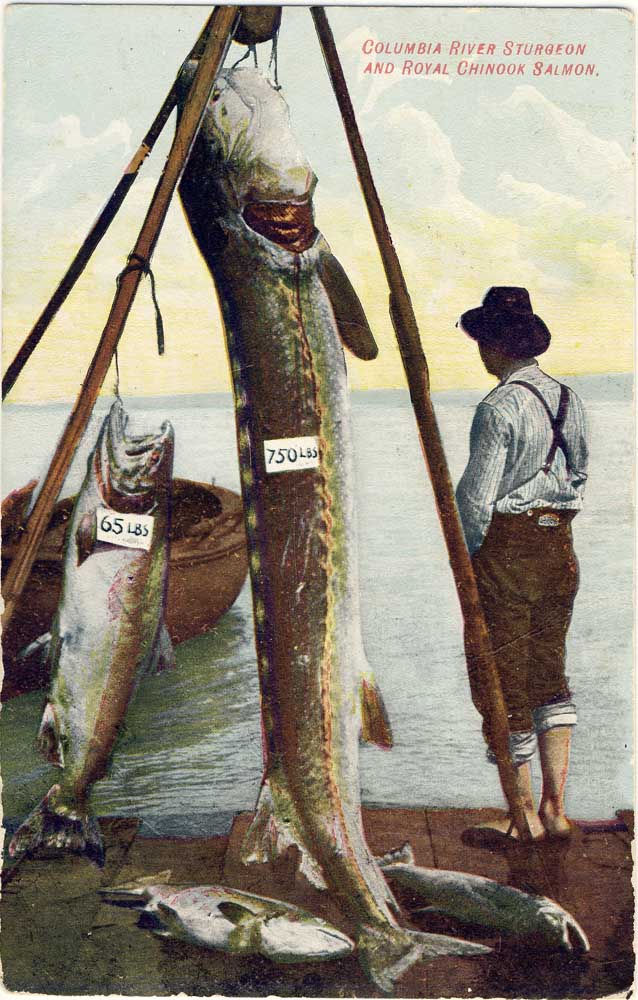

- Scientists are learning that large, mature sturgeon like the one pictured here on a century-old postcard are key to the health of the Columbia River's population of the ancient fish.

As Northwest scientists work to understand why 80 large sturgeon suddenly died in the Columbia River last month, a Bonneville Power Administration research project focused on sturgeon sexual maturity are finding old fishing tackle and other factors impact the reproductive cycle of the ancient fish.

Trending

The study, now in its 15th year, examines overall health, impact of sea lions and frequency of capture in the catch and release fishery below Bonneville Dam.

As part of the project, each year, BPA biologists help researchers from Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, capture 60 sturgeon. The large fish are usually anywhere from five to 10 feet long and can weigh hundreds of pounds.

Once caught, scientists check for tags to see if the sturgeon have been captured before (some have been caught and assessed up to six times). Biologists also biopsy reproductive organs to find out when the fish will spawn. The information gathered is analyzed and cataloged, and over time, paints a picture of how well the river’s white sturgeon population is performing.

Trending

“One thing we’ve learned is that female sturgeon do not sexually mature until they’re at least 18 to 32 years old,” says Dave Roberts, a BPA fish biologist. “We also know females only spawn about once every three years. That’s one reason a big die-off of older fish like we saw this year is especially troubling.”

Scientists also know sturgeon-spawning success is best during high-flow years when the river creates turbulence over rough substrate or rocky-river bottoms. This year’s low-warm water likely means many fish didn’t spawn. This became evident during last month’s research when scientists found a high number of females had not spawned.

“The eggs of females will simply be resorbed back into the fish’s system, they’ll wait for better spawning conditions, hopefully next year,” says Roberts.

After capturing the huge fish and taking biopsies, biologists also check out the animal’s overall health. They say it’s common to find old fish hooks stuck inside the animal.

“We often find fishing tackle that has passed through the digestive track with lines protruding from the vent,” says Roberts. “In fact, during the last study we found one fish that had three hooks lodged in its system, but we could only remove two before we released it back to the river.”

BPA spends about $1.5 million per year (including this study and others) to evaluate the fish in the lower Columbia River. The research offers insight on how scientists should manage the species that is the largest fresh water fish in America.

Researchers estimate there could be as many as one-million white sturgeon (all age classes) from Bonneville Dam to the Columbia River’s mouth. However, with none of the fish spawning until they are at least 18 years old, protecting the river’s older fish seems imperative.

“It’s a resource that’s not replaceable,” says Roberts. “Those big spawners, we know how valuable they really are.”