Northwest Nature Log Nighthawks: Welcome insect-hunters of summer

Published 9:30 am Tuesday, May 26, 2015

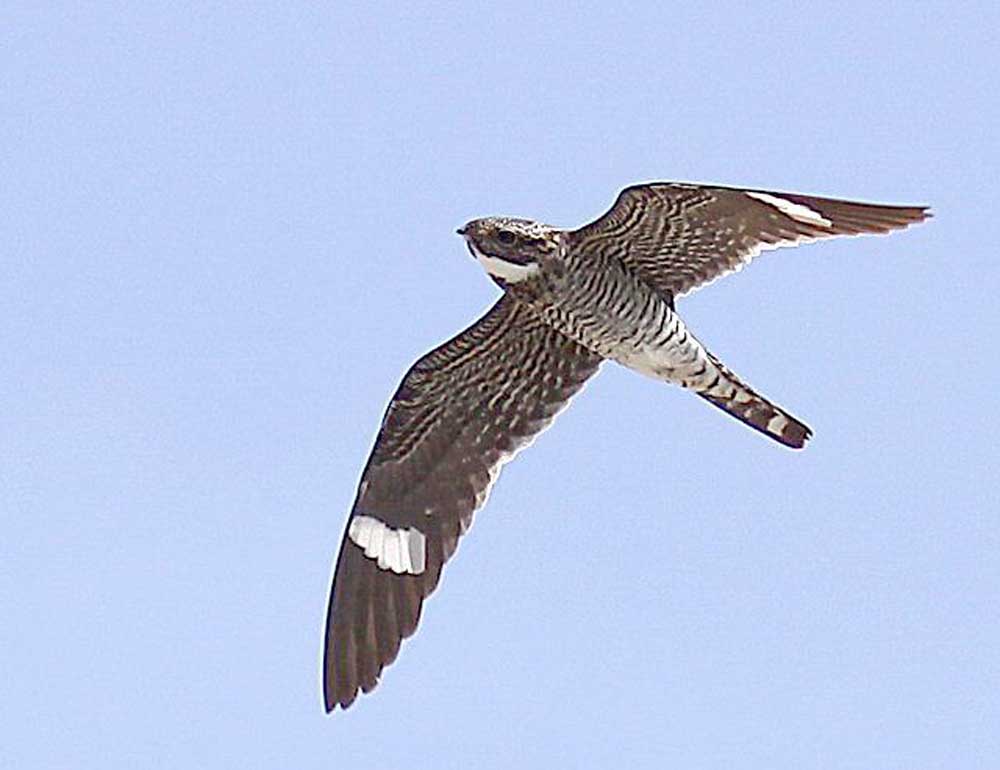

- Cathy Miller photographed this common nighthawk in May 2010 on Dewees Island, South Carolina, during the Charleston Audubon Spring Bird Count.

Peent, peent, the high, nasal call drifted through the warm summer night. It was dusk, and common nighthawks circled and dove across the deep azure sky.

Trending

Looking vaguely like oversized swifts or swallows, nighthawks were another familiar and welcome bird that I came to know when I was a child.

Nighthawks are not true hawks, or raptors. They’re in the nightjar family and are related to other night hunters like whip-poor-wills. They are on the small side, about nine inches long, with a 24-inch wingspan. “Night” is actually a bit of a misnomer as well, because they are most active at dawn and dusk. They hunt flying insects, so they are a good bird to welcome to the neighborhood.

Nighthawks are also known as “bull-bats.” The origin of this name is twofold: their flight pattern does resemble the dodgy, fluttery flight of a bat, and during mating flights, the males can make a booming sound with their wings, as air is forced over the feather tips.

Trending

In the late 1950s, nighthawks weren’t hard to find, even in cities. They returned from their winter sojourn in South America just in time to benefit from the insect hatches of early summer. The sight of their dark, scythe-like wings cut with white chevrons was a sign that summer had arrived.

On warm evenings my dad and I would sit on the front steps of our house while he watered the grass. This meant that he held the hose and aimed the nozzle here and there on our patchy front lawn. I sat next to him, feeling the sun’s warmth still present in the cement steps.

Usually there was a Portland Beaver baseball game on the radio, and we could hear the announcer’s voice growling from the living room. Above us, the nighthawks made their living, dipping and swooping, hawking mosquitoes and moths attracted to the street lights’ glow. That sweet, nasal call was a comfort, something that I thought would always be there.

There was a small cafe farther up the street called the Nighthawk Restaurant. The neon sign out front actually sported the silhouette of a nighthawk. For many years I thought that it was named in honor of the bird, rather than for the folks who stayed late into the night, drinking beer and eating greasy-spoon food.

Nighthawks are harder to find in the cities these days. Their preferred nesting sites are flat, gravelly spaces. Roofs used to be the best, but open spaces on the ground will do. Graveled roofs used to be fairly common, but cities have changed. Open gravel on the ground is a dangerous place to build a nest. Not only are there cars, but dogs, cats and even unwitting people can disturb a barely visible nest.

It’s reassuring to know that nighthawks fall into the “least concern” category of endangerment. It seems that they have relocated to less populated areas. East of our Peninsula, over areas where flying insects can be found, you can still hear their haunting call and see those chevroned wings, flicking and folding, carrying the little nighthawks through the darkening sky.