Northwest Nature Log The ivory-billed woodpecker — rare bird, indeed

Published 7:22 am Wednesday, March 18, 2015

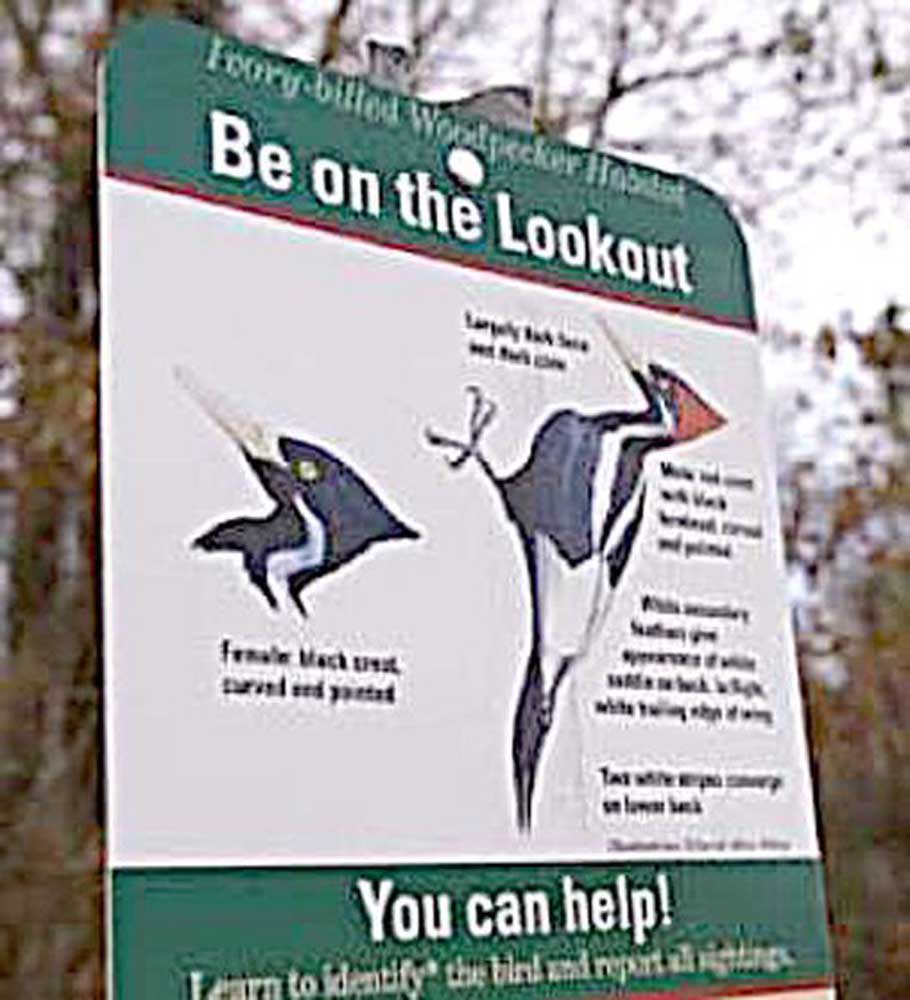

- A trail-side sign provides forest visitors with a guide to identifying one of America's most sought-after birds.

On a mid-winter day in 2004, a lone kayaker was making his way along a quiet stretch of water called Bayou de View in the Big Woods of Arkansas. As he paddled silently on this misty tributary of the White River, he got a glimpse of a woodpecker in the trees at the water’s edge. The bird flew away from him, flashing clearly marked black and white wings, into the mossy depths of the cypress swamp. Although he wouldn’t describe himself as a “serious” birder, he knew what woodpeckers in the area looked like. He posted his sighting on a local canoeing chat room.

Trending

What he saw was probably an ivory-billed woodpecker. Since this bird “officially” became extinct 60 years ago, he didn’t claim that he saw one. But he did know the difference in feather pattern and bill coloration between an ivory-billed and its close relative, a pileated woodpecker. But he just reported what he saw, without naming it. This posting, along with sightings by a few other reputable birders, and one blurry video, generated incredible interest in the birding world.

Eventually, the prestigious Cornell Lab of Ornithology got involved and spent over two years studying the data, the video, and looking for the bird. The video was slowed down, sped up, stopped and dissected in every possible way. Unseen woodpeckers heard drilling on tree trunks were recorded; the number of taps per minute counted and analyzed.

I think the reasons for all of this activity are valuable to consider. Why spend time and a lot of money to determine if this Woody Woodpecker-looking bird is extinct or not? What good will it do humanity either way?

Trending

On the tenth anniversary of this activity, the two individuals who first saw the bird and then videoed it were interviewed. One of these men is a wood artist, the other is a professor at the University of Arkansas. They both gave up two years of their lives to try to prove or disprove the findings. When asked why, they both became thoughtful and quiet. They both mentioned the great benefit to land conservation in the area. Many thousands of acres have been added to the Big Woods refuge. These woodpeckers require hardwood and cypress swamps like the ones in eastern Arkansas. The thought is that this could have been a lone male ivory-billed traveling north, driven by the urge to find a mate. Behind their words , though, was the sense of mystery and the timelessness of this quest. Of days spent deep in the wetlands, listening and looking for what became known as the Holy Grail of Birds.

When Cornell Lab finished all the analysis, they concluded that these were probably valid sightings, that an ivory-billed woodpecker was seen. It’s doubtful that so many individuals would get sightings, or partial sightings, of just one bird. Big Woods has enough remote, inaccessible areas that there could be a small colony that still exists. But the money and the sightings dried up after a few years.

The man who saw the bird first is philosophical: we will never know. We don’t need to know, because the lesson is inherent in the search. We’ve lost the passenger pigeon, that poor, overworked symbol of extinction. Think of this: Hazel, the last passenger pigeon in the entire world, died alone of old age, in a zoo. We can do better than that.

I like to think that we are becoming aware of the crucial need to live together with all the critters who share this web of life with us. The loss of one species vastly diminishes all of us, because every living thing has intrinsic value.

And that someday it will not be so unusual for some lone kayaker to again look up and see a black and white bird open its wings and glide silently into the dense, impenetrable mist of the cypress swamp.