The Blob 2014 taste of things to come for migratory fish

Published 5:54 am Tuesday, January 27, 2015

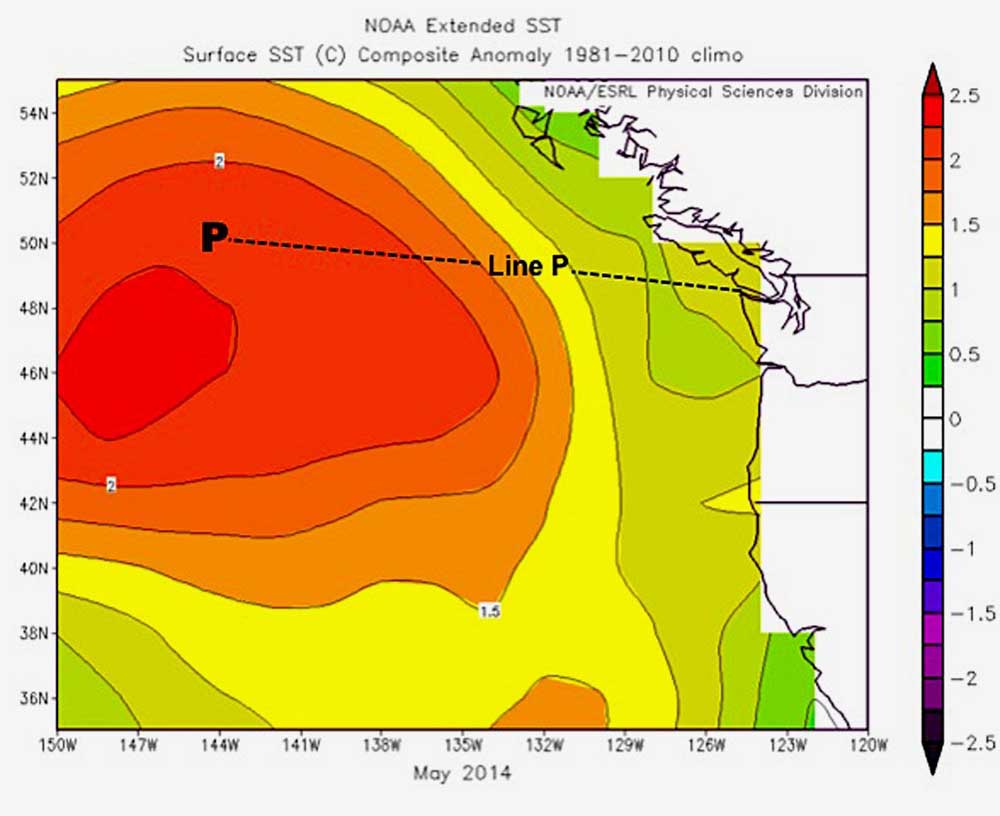

- “The Blob” is a giant pool of warm water that formed in the North Pacific and had a particularly noticeable influence on Pacific Northwest weather last year. Out in the ocean, warmer-water species are being observed. Cold-water species like salmon are likely to be negatively impacted as this warming becomes a long-term issue.

This is the first of two stories that will look out how scientists are interpreting strange weather and water patterns and unusual animal sightings in 2014, and what it could mean for salmon, fishermen and the economy.

Trending

By Katie Wilson

kwilson@chinookobserver.com

Pygmy killer whales and tropical birds spotted off the coast of California; massive squid, rarely seen farther north than Oregon, are bing found spooling through water in Alaska along with sunfish and skipjack tuna; sea turtles washing up on the Long Beach Peninsula before Christmas, disoriented and too cold.

Trending

The planet’s hottest year on record was also a year of strange sightings on the West Coast. Though the sightings have more to do with wind patterns and a surge of warm water moving through the area than with climate change, scientists say 2014 was a taste of what is likely to come as climate change reshapes the Pacific Northwest, its people, its animals, its salmon.

But, first, there is a blob — the Blob, actually.

“It’s a very technical term,” joked Washington State Climatologist Nick Bond, who named “the blob.”

Bizarre wind patterns helped form this thick mass of warm water off the West Coast back in 2013. When winter hit, the blob persisted, along with its associated wind patterns, warming nearby waters, drawing warm water species to the area and even affecting the weather. Communities at the mouth of the Columbia River enjoyed a hot summer and a mild winter.

Temperatures in the blob were approximately 3 degrees C warmer than normal. A recent study by Canadian scientist Frank A. Whitney, not yet published, found lower productivity of plankton in the blob’s hot waters last spring and summer. These microscopic plants are an important indicator of ocean health,

“This is basically bad news for Pacific Northwest salmon,” Bond said about the blob. “In particular, the year class that would be going to sea next spring.”

Right now, those salmon are just little guys hanging out in their freshwater habitat. But the conditions they encounter in their first few months at sea are crucial when it comes to determining how many will survive and come back to be caught by fishermen or to escape up familiar streams to spawn.

Though things like the blob have happened before — Bond says they have reliable records back to 1980 and a “good idea of what’s going on back to 1950” — this particular blob was “pretty extreme in terms of how much warmer it was than normal and its magnitude.”

When masses like the blob form they tend to stick around for a while. Then they slowly get torn apart and dispersed as weather patterns shift. The same thing is happening to the blob now. The warm waters we’re still seeing are a kind of “hangover from the blob,” Bond said.

The horror itself is disappearing. For now.

As Bond puts it, “The weird weather we had in the winter of 2013 and through 2014 was kind of a fluke.”

The climate is built to contain these kinds of variations.

“But on the other hand,” Bond continued, “I think we are seeing slow warming of the oceans. In a way, we can learn from these kinds of incidents about the sort of changes we are expecting to see as a part of climate change. … We are quite confident it’s already happening. We’re confident it’s going to continue. Warming like this is on the way.”

According to a 2006 study focusing on Washington state, the U.S. is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, a primary driver of climate change. Washington contributes about 85 to 90 million tons each year to the global total from energy use — about 0.3 percent of worldwide emissions, according to some estimates.

This puts Washington’s yearly emissions per capita per person at about 13.5 tons of CO2, more than the world average of 4 tons per person but lower than the U.S. average of 20 tons per person. For that, we can thank the dams, the study’s authors said.

“This reliance on [electricity generated by dams], though damaging to salmon and freshwater ecosystems, means that Washington residents lead somewhat less carbon-intensive lives than most Americans,” the study says.

But that number — 13.5 tons per person — continues to grow and is projected to swell over the next 25 years as the population grows.

With climate change, researchers expect a laundry list of changes in Washington: more frequent and more severe wildfires, rising sea levels, warmer and more acidic oceans, seasonal drought, hot and dry summers, cold winters.

In such a slippery environment, certain species will thrive, some will leave as others move in. Some will vanish.

Some are already on the move.

A recent study published in Progress in Oceanography predicts massive shifts of West Coast marine species — everything from sharks to salmon — northwards an average of 30 kilometers per decade.

“As the climate warms, the species will follow the conditions they’re adapted to,” said Richard Brodeur, a NOAA Fisheries senior scientist at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and co-author of the study.

As the species shift — not necessarily in lockstep, prey and predator together — there will be “winners and losers that we cannot foresee,” he said.

And what it means for Washington’s commercial and recreational fisheries is anyone’s guess.

Commercial fishing jobs and the millions of dollars of personal income they generate may barely register on Washington’s overall net earnings, making up a small percentage of what keeps the state moving. In communities like Pacific County, however, where all types of fishing and seafood processing has been a traditional way of life and remain vital to the economies of many small towns, those earnings loom large.

And among fish, few species loom larger here than salmon.

The phrase “climate change” is not directly referenced in the discussions fisheries managers have when they set salmon seasons each year in a process called North of Falcon, said Doug Millward, of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and a member of the Salmon Technical Team that informs the North of Falcon process.

Still, the vast suite of data they examine each year tells the story of climate change: rising temperatures, ocean acidification, habitat loss and gain, ocean health, stream and river health, salmon health.

“It’s definitely there,” Millward said. “Even if it’s not stated as such.”

Researchers know a lot about what needs to happen in freshwater to help salmon thrive and they say the quality of freshwater habitats could make or break future runs. The ocean is a different story. A warmer, less productive ocean — the blob was just a taste — is a huge unknown.

“What’s hard is that we can’t tease apart the physical and biological factors in the ocean that well,” said Lisa Crozier, a research biologist with NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center. “In changing scenarios, we have no idea what ocean survival is going to be like.”

Numerous agencies and groups have focused attention on freshwater habitat and fish passage over the years and Crozier says this work is even more important in the face of climate change. Freshwater is where salmon spawn and it’s where some species could retreat if ocean conditions become unbearable. Steelhead and sockeye salmon, for example, have the option to become entirely freshwater residents, Crozier said.

Salmon, in general, are adaptable and have survived drastic climate shifts before. Crozier has already seen changes in how some sockeye populations are changing the timing and location of their migrations. Some of these changes are part of the fish’s innate ability to be flexible, but Crozier and other researchers have seen what they believe are evolutionary changes in the fish as well.

“If we could remove the human impacts” — dams, pollution, harvest — “they would do just fine,” Crozier said. “All these things are things we’ve done which push them in the same direction climate change is pushing them.”

Scientists like Crozier believe salmon will remain off the West Coast for years to come, but their life cycles may take on a different shape. In some places, they are already changing. And where people were once able to fish and find abundance, they have to look in new places.

James Gustave Speth, dean of the school of forestry and environmental studies at Yale University and former chairman of the President’s Council on Environmental Quality, said in the early 2000s, “The world we have known is history.”