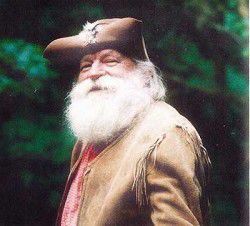

Dallas McKennon, man of merry heart, is remembered by friends up and down the coast

Published 5:00 pm Monday, August 10, 2009

- Dallas McKennon, man of merry heart, is remembered by friends up and down the coast

RAYMOND – Dallas McKennon loved stories and he loved an audience. He got both Saturday in Cannon Beach during a memorial service celebrating his life.

Trending

An overflow crowd at the Community Presbyterian Church in Cannon Beach listened to McKennon’s songs, family tales and memories from television personalities who worked with the actor and voice master.

McKennon, who lived in Cannon Beach from 1968 to 1993, died July 14 of age-related causes at the Willapa Harbor Care Center in Raymond. He was 89. McKennon is survived by eight children, 21 grandchildren and 20 great- grandchildren. Betty, his wife of 66 years, lives in Raymond.

“He had a merry heart and was full of joy,” said Richard Gorsuch, a Cannon Beach artist who knew McKennon.

Trending

The service began and ended with a medley of songs, played and sung by some of McKennon’s eight children, while the audience clapped along to the music.

Rev. David Robinson, pastor of the Community Presbyterian Church, recalled when McKennon would visit a church camp in the mid-1980s and tell campfire stories to kids about bears chasing teenagers into the forest and make sounds of mountain lions and monkeys.

“The teens were hanging onto every growl and sound Dallas made,” said Robinson, who was a youth pastor then.

Although McKennon moved from Cannon Beach in 1993, he would return to tell stories about Zachariah and Isaiah. He would ask Robinson, who had since become the church’s pastor, which Jewish dialect he should use.

“He must have had seven, eight, 10 of them,” Robinson said. “He brought Zachariah to life. He wrote songs just for the stories.

“What a gift to have known this man,” Robinson added.

McKennon’s daughter, Dalene Lackaff, said McKennon learned to mimic the sounds of farm animals when he grew up on a farm in Eastern Oregon. At age 15, he was hired at a local radio station to read stories, and he used the different voices he had developed. They seemed so authentic that the station manager told him, “I’m hiring you, but certainly not all those others.”

After World War II, McKennon played “Mr. Buttons” with his talking mouse, “Zipper,” on a KGW Radio children’s show in front of a live audience.

At the service, Jim Allen, who also did a radio and television children’s show for decades as “Rusty Nails,” said he met McKennon in the 1940s. He once watched McKennon play the narrator in a Coaster Theatre production of “Our Town.”

“He was far better than I was,” said Allen, who had played the same part in a production elsewhere. “He had a natural ‘old man’ thing about him.”

In 1951, McKennon played a “ride-on” part as a miner riding a horse in a scene of the James Stewart Western, “Bend of the River,” produced near Mount Hood. After that experience, he moved his family to Hollywood. There, he worked as a children’s show actor, appeared in several movies and television shows, did the voice-overs for Walt Disney cartoons and commercials, taught vocal artists and produced music albums.

He was nominated for an Emmy award for the television children’s show, “Captain Jet,” where he wore a “space suit” with rubber tubing around the arms. With a full beard that seemed to get bushier with the years, McKennon probably was best known for his ongoing role as Cincinnatus on television’s “Daniel Boone.” Of the 30-plus voices he could do, McKennon was known for “Gumby,” “Archie Andrews” and Woody Woodpecker’s archenemy, “Buzz Buzzard.”

Kirby Brumfield, who interviewed McKennon when Brumfield worked for KATU television, quipped that McKennon “could have conducted a wonderful interview by himself.”

Brumfield recalled when he worked at Portland General Electric and hired McKennon to portray “Izard the Wizard” on a PGE promotional film. McKennon wore a jester’s costume, and on a quick stop to a grocery store while heading to the location, McKennon went inside the store and started “putting on a show.”

“It opened my eyes,” Brumfield said. “Just because you’re in costume doesn’t mean you can’t go out in public.”

McKennon’s son-in-law and former Cannon Beach artist, Frank Lackaff, said he learned early not to ask Dallas what was new with him.

“That was a big mistake,” Lackaff said. “It was like asking a hypochondriac, ‘How are you feeling?'”

McKennon’s constant admonition, noted Lackaff and McKennon’s children, was to “use your talents,” and, although they tired of hearing him repeat it constantly, Lackaff admitted, “he did that better than anyone.”