Chapter 3: Adventure, danger and salmon as CRPA heads north to Alaska

Published 4:00 pm Tuesday, January 30, 2007

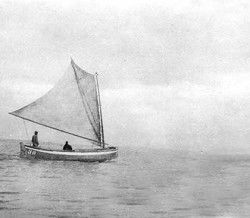

- In keeping with standard practice at the time, once the CRPA's new cannery at Nushagak finally got going, only white men were permitted to engage in the dangerous but financially lucrative activity of fishing. They used distinctive boats like the one pictured here. Chinese and Japanese contract workers manufactured cans on the spot using rolls of tin and lead-based solder and then filled and cooked the cans in steam retorts, sort of like giant pressure cookers. Hired by middlemen including the colorfully named Ah Dogg, these so-called Oriental crewmen produced more than 1.2 million one-pound cans of salmon the first season.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Irene Martin, the foremost historian of the Columbia River fishing industry, has written a series of articles about the Columbia River Packers Association.

The CRPA was the product of a historic merger of several of the Columbia’s major salmon canners in 1899. It dominated the industry for most of the 20th century, employing thousands of individuals on both sides of the river, in Alaska and elsewhere. Eventually changing its name to Bumble Bee Seafoods, CRPA is a fascinating story of capitalism, adventure and social change.

Eventually to be gathered in a book, this series represents years of effort undertaken at the behest of Bumble Bee retirees. Originally started by historian Roger Tetlow, who before his death in 1999 lived on the Peninsula and in Hammond, Ore., the CRPA project was taken up by the Chinook Observer as part of its commitment to preserving and telling local history.

We are proud to publish this series. We will soon begin soliciting pre-sales for the richly illustrated book that we anticipate publishing in about one year.

“We propose to carry on the fishing industry on a scale which has, perhaps, never been equaled in this country, certainly not on the Pacific Coast.”

Samuel Elmore was not exaggerating when he informed a Daily Astorian reporter of his intentions in the spring of 1899. He was now in charge of the day to day operations of the CRPA, although his official title was vice president and Chairman of the Executive Board of the Columbia River Packers Association. He added, “The Association was organized for the sole purpose of conducting the fishing and packing business on as large a scale as possible, and it intends, of course, to enter any field now uncovered which seems to promise a fair return on the additional capital required.”

The “Combine,” as it was still being called in the Lower Columbia area and in Astoria, was already getting its fair share of the salmon entering the river on their way to spawn. CRPA owned several seining grounds and leased others. It had a large fleet of gillnetters, with numerous receiving stations along the lower river. It also owned or leased a number of productive fish traps. Along the Oregon Coast a number of small canneries and receiving stations delivered salmon to CRPA tenders that brought them ice and picked up fish. In the upper river, the new Rooster Rock cannery produced a portion of the pack. In order to expand, Elmore had to look further afield than the Columbia.

In 1889 Elmore and his partner George Sanborn had already built a cannery at Pavlov Harbor on the east side of Chichagof Island, in Southeast Alaska. They operated under the name of Astoria and Alaska Packing Co. In the spring of 1890 they moved the cannery to Point Ellis, on the eastern side of Kuiu Island, and produced a pack in 1890 and 1891. In May 1892 the cannery burned, ending the enterprise. But the experience had taught Elmore what was needed to succeed in Alaska.

In the spring of 1900 Elmore sent Oluf Pedersen, one of his longtime employees, north to Bristol Bay, Alaska, with instructions to locate a good cannery site, preferably in the Nushagak area. Bristol Bay is in the southeastern corner of the Bering Sea just north of the Aleutian Islands in what was then the Territory of Alaska. Five rivers feed into the Bay, including the Nushagak, the Kvichak, the Ugashik, the Naknek and the Egigik, all prolific producers of sockeye or red salmon.

When Pedersen returned in the fall, he brought back maps and drawings of the site he had located for a new CRPA cannery. He had discovered that many of the good sites had already been taken by other packers. Thirteen canneries were operating on the bay at that time, including the Alaska Packers Association, F.S. Peterson, the Alaska Salmon Company, the North American Salmon Company, the Alaska-Portland Packers’ Association and the Pacific Steam Whaling Company. In the following year, 1901, nine more canneries sprang up in the same area.

A site on the tundraThe site Pedersen had chosen was located on Clark’s Slough which fed into Nushagak Bay. Although the surrounding terrain was tundra, the site was sheltered from the cold Arctic winds by low hills. It was close to the fish supply in Bristol Bay. Elmore gave the go ahead to the project after consultation with A.B. Hammond.

The company appointed Pedersen head fisherman, or beach boss, of the proposed cannery. He agreed to take the CRPA outfit to the site, and “aid and assist and work for the first party (that is CRPA) in the construction, completion, and operation of said cannery in its various departments … and perform such work as requested of him, at all times and during all days, it being understood there will be no layoffs for Sundays.” His pay was set at $1,800 per year.

The general manager of the expedition was Christian Andersen, an experienced cannery man as well as a surveyor. His salary was $2,000 per year, plus the privilege of taking his wife along, which he decided to forego. Fred Ferchen of San Francisco became cannery superintendent, and John Gustafson, head carpenter. CRPA also hired a young doctor, W.B. Braden, of Portland, to accompany the men, at a salary of $100 per month plus room and board. He was also allowed to charge 50 cents for each visit he made to an employee.

Locating a ship suitable for the enterprise turned out to be a difficult task, as most of them were already engaged by other canneries. However, Elmore finally located the bark Prussia, a coastal sailing vessel with a burthen of 1,131 tons. CRPA chartered the vessel from its owner’s agent, Renton, Holmes & Co. of San Francisco, for an upfront fee of $3,000, plus $1,500 per month for as long as the charter lasted. CRPA was also responsible for all crew wages except for the captain’s, and all necessary provisions.

A second vessel, the Despatch, was also chartered to go ahead of the cannery crew with all the materials needed to construct the cannery and its outbuildings. It also carried the construction crew and the cannery machinery. The Despatch was a small steamship of 539 net tons, and had the advantage of being fitted with numerous cranes and winches for offloading the heavy cannery machinery and other materials.

John Gustafson and Chris Anderson were responsible for designing the various buildings needed and obtaining the materials. They had less than a month after arriving in Nushagak to build the cannery, bunkhouses, wharves and a warehouse, so they designed the structures and made a list of each piece of lumber needed with the dimensions given for each so that the Astoria Box Co. could cut each piece exactly to size. Each piece was numbered and labeled, and plans drawn up for the carpenter crew showing where each piece should go. They also prefabricated 244 windows ready for installation.

Orders went out for cannery machinery, including six double-ended retorts or cookers, especially built to CRPA specifications. These retorts were a recent innovation. They opened at each end, so that the canned salmon could be put in one end, cooked and pulled out through the other end, streamlining production. John Gustafson had invented a fish elevator, a device for conveying fish from the fish tender up to the fish dock. This machine was especially useful in Bristol Bay, with its 20-foot tides, and so it was manufactured and sent north.

Food supplies for 75 men amounted to 3-1/2 tons of potatoes, 375 pounds of coffee, 350 pounds of pilot bread, plus two railroad cars of canned and cured meats, among other edibles. Pipe and chewing tobacco and cigars were not omitted from the list. The company hired three women who were willing to make the trip, Kate Kipper, Annie Marttala and Ida Osterback, as cooks. The company also stocked clothing, boots, coats and blankets to sell to crew members and workers as needed.

Elmore began to sign up his crew in March and April 1901. He needed fishermen, mechanics, carpenters, a beach crew and a Chinese crew. He chose many of the fishermen and others himself from a list of men he knew and trusted, but when it came to the Chinese, he relied on a contractor, Hop Chung Ling Kee Co., of Portland, to provide the Nushagak cannery with a “sufficient number of skilled salmon packers, including a certain Chinaman named Chang Sen, who shall act as foreman of said gang, to pack at least 1,500 cases of 48 one-pound cans of salmon within 11 hours each day provided sufficient fish could be procured. The work required of said laborers to consist of taking the raw fish on the dock, putting them through all the necessary processes of cleaning, canning, packing, lacquering, labeling, nailing the canned salmon in boxes and piling such boxes in tiers, eight boxes high, at such points as directed.”

For this, the contractor received fifty cents a case, out of which sum he paid the members of his crew. CRPA agreed to pay the wages of the foreman, a tester, and a cook, and stipulated that they would provide housing and mess facilities for the crew plus sufficient coal to heat those buildings.

CRPA also agreed to furnish the Chinese crew with 25,000 cases of empty cans to start the season’s work, and also “a sufficient number of filling, topping, soldering, and washing machines to do the work required of the crew.” They agreed to pack all king salmon by hand at the rate of not less than 500 cases per day. Unfortunately, the Hop Chung Ling Kee Company was unable to produce enough Chinese laborers to do the job and Elmore had to rely on another contractor, Ah Dogg, to fill out the crew at the last minute with 22 Japanese cannery hands.

On Feb. 12, 1901, Samuel Elmore sent 10 fishermen down to San Francisco to help bring the bark Prussia back to Astoria. Carpenters had been building eating and sleeping facilities aboard the vessel for the men who would be making the Alaska voyage. The Prussia docked in Astoria on March 2, and took on 350 tons of coal. Twenty-five thousand wooden cases of cans also made up the cargo. Canning machinery included two Jensen can topping machines and four retorts. In addition, 16 gillnet boats, each completely equipped, and 12,000 board feet of lumber were loaded.

The steam schooner Despatch arrived at the CRPA dock on March 6 with a full crew under the command of Capt. Victor Johnson. As soon as she arrived, a swarm of carpenters began installing sleeping and eating facilities for the construction crew and others. Then the lumber for the mess house, storerooms, office, bunkhouses and main cannery building and wharf went aboard, along with a carload of roofing iron. On deck were the remaining two retorts, five more gillnet boats, two skiffs, and 30,000 feet of lumber, plus another 43 tons of coal. A new launch, the Occident, designed by John Berglund for use at the Nushagak Cannery, was also hoisted on deck. On March 14, the Despatch left the CRPA dock.

On that day a tradition was born which was observed for many years, that of making the Alaska departure a celebration. Early in the morning, a crowd began to gather at the 6th Street wharf. Samuel Elmore, determined to make the occasion a happy one, had hired the Astoria Brass Band to play festive music while the passengers walked up the gangway. Samuel Elmore, George and William Barker were on hand to wish the members of the expedition good luck.

Although the men and women aboard the Despatch didn’t know it at the time, they were in for a memorable and hazardous trip. The rough Columbia bar kept them in the river for another day. When they finally put to sea, the March winds kept the ocean waters rough for the long voyage to Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians. They used more coal than planned, so the captain decided to load more, although they had to wait two days to get delivery. On April 2, the Despatch, the first vessel to reach the Bering Sea that year, left Dutch Harbor and set out for Nushagak. Chris Anderson wrote to Samuel Elmore about this part of the trip.

“We proceeded on our course until we were about 140 miles west of Nushagak where the Despatch encountered ice fields which made in necessary for her to cruise about to avoid being closed in. On April 4, we struck open waters which lasted nearly all day but then we encountered heavier ice and began beating about for an opening. We spent all the next three days in vain trying to find an opening in the ice.”

A second attempt was made and this one also ended with their return to Dutch.

A dreadful voyageAll on board suffered from the cold weather. On May 11, 1901, Anderson wrote to Elmore about the hardships:

“Owing to the overcrowding of the steamer and the behavior of the officers, the voyage entailed untold hardships. On many occasions, the passengers’ beds got wet from the high seas and then froze stiff and the engine room, being the only place of shelter on the vessel, was crowded all the time. The food, on account of lack of facilities for so many, was very poor, and altogether, the trip was such that we think the laws governing such matters might be invoked in this case as a warning to others.”

This letter was signed by all of the 57 cannery workers on board.

Anderson was probably not aware that the Despatch was rated as a 40-passenger steamer and carried only enough lifeboats and life preservers for 40 persons. The galley and eating areas were designed to service that many also. The extra 17 CRPA passengers must have strained the ship’s facilities well beyond their limit.

On the third try the Despatch left Dutch Harbor and headed east for Nushagak again, but got stuck in the ice for three days. During this time, ice several inches thick formed on the smoke stack while 150 pounds of steam was being carried. For several days the sleet froze so hard against the side of the cabins that an axe had to be used to cut it away before the door could be used. The vessel was so heavy with ice that she rolled severely, and would not answer her helm.

Finally the weather moderated and the steamer moved eastward, but they were not out of trouble yet. Anderson wrote:

“On the 24th of April in the early morning we encountered some soft scattering of mushy ice and the captain refused to proceed, claiming that it would be dangerous to do so. In the afternoon we asked the captain to try a scheme originated by Oluf Pedersen, namely to put some heavy planks on the bow of the steamer at the water line. The captain refused to listen to that and simply laid still although the ice was of such a nature that it could hardly do anything but scratch the paint. On April 25th, we laid around all day. April 26th, the captain did finally try Pedersen’s scheme and it seemed to work all right. However, the captain said it did not protect the vessel and we simply remained where we were.”

Both the captain’s and Anderson’s attitudes are understandable. Anderson wanted to get to Nushagak as soon as possible in order to get the cannery up and running, while the captain’s first responsibility was to the ship and its cargo. He knew how changeable the weather could be in the Bering Sea at that time of the year and wanted to avoid having the vessel caught in the ice and disabled. Anderson’s letter told the rest of the story.

“On April 29th it began to blow. At eight a.m. we started in a half-hearted way, sounding every four ship’s lengths. About 10 a.m. we stopped completely. Oluf Pedersen offered to take a fish boat and go for a pilot and find out where we were and although we might have supposed that the captain would have been ashamed to accept the offer, he fell in with it. However, the wind got so strong that Oluf would not go. April 30th, it blew a gale and anchored. May 1st, heavy gale all day and the ship would not lay at anchor but kept position by steaming against the wind. May 2nd good weather and in the morning we started at slow speed, land in sight all the time. May 3rd, laid at anchor in fine weather. About 9 a.m. Oluf Pedersen started off in a fishing boat for a pilot. From 3 to 6 p.m. We moved along leisurely and then anchored between Cape Etolin and Protection Point. May 4th, at 6 a.m. Pedersen returned with Otto Larson as pilot. About 10 a.m. we raised the anchor and started up the bay. At 2 p.m. we got stuck on a shoal which is plainly marked on the map. About midnight we got off the shoal. On May 5th we dropped anchor off Ekuk Village.”

“After determining the site in Clark’s Slough we asked the captain to move up off Clark’s Slough so we would not have so far to tow the lighters but he remained at Ekuk Point thus compelling us to tow seven miles although the position at Clark’s Point would have been perfectly safe.”

The men standing on the deck of the Despatch, anchored in ice cluttered waters, must have looked around at the frozen tundra around them and compared it unfavorably with the familiar green of the Columbia. Chris Andersen set all the men to work using the steamer’s winches to help move the heavy equipment onto the lighters which were then towed to the cannery site on Clark’s Slough. First ashore were the 30,000 feet of lumber, to be immediately transformed into a bunkhouse and cookhouse. Their only shelter was the Despatch, which would leave as soon as she was unloaded. Shelter was the top priority, but it was not their only problem. Anderson wrote a letter to Elmore on May 10.

“At last we have reached the promised land and commenced building. I enclose a piece of tracing cloth showing the position of the cannery. I had to pay $1,000 for the site. I had to promise the seller that I would pay him cash, so if I can draw the money here, I will. The site is a good one as far as I can judge but I have to get the water about a mile distant from a spring and it will be hard scratching to get the necessary piping or flume lumber. The Occident is very poor and the engine breaks down all the time causing aggravating delays. More serious still is that the coal we have is the worst possible, it will hardly burn with a flame and ruins the grate bars. I am forced to get 20-30 tons of coal from the Despatch.”

Meanwhile, on April 8, the Prussia left Astoria for Nushagak. It had become obvious by this time to Samuel Elmore and George H. George that the Despatch and the Prussia would not be able to haul all of the supplies needed for the first year in Alaska so they appealed to A.B. Hammond in San Francisco to buy another vessel. He found a small two-masted schooner named the Antelope which was owned by George Hume. She went to Astoria for her load of cargo, and on May 4th set sail for Nushagak. On board were the remaining supplies needed to complete construction of the cannery and outbuildings, plus wooden shooks for making up extra boxes, should the pack prove larger than anticipated. Samuel Elmore wrote a personal letter to Anderson on May 4, 1901 that revealed his anxiety about the endeavor. (Bear in mind that he had not yet received any of Anderson’s letters to him, nor any other word about the expedition since it had left Astoria).

“We are awfully anxious about the outcome of the venture and I want to call your attention again to the fact that the fish run only twenty days and you must pack what you get each day for when the fish have quit running, the pack is up.”

When the Prussia arrived the crew was unable to unload her cargo because they had nowhere to store it. Anderson finally offloaded the cans and piled them outdoors and covered them with a tarpaulin made from the Prussia’s sails. He wrote to Samuel Elmore:

“I do not think that when you made the arrangements by which we were to make 25,000 cases of cans here you realized what it means to be thrown on the beach among ice and snow with a concern of this kind especially when now one week before King fishing and two weeks before Red fishing we have no warehouse and not a stick of lumber. Of course if we get the cases made and filled with fish and be forced for lack of room to pile them in the ship as we go along without lacquering and labeling, I shall do that.”

Occident or AccidentFurther problems arose with the Occident, which had proven to be an “expensive toy,” according to Anderson. Her engine was too small to serve her purpose, she constantly broke down, and finally one of the crew members scratched out the “O” in the name and painted an “A” in its place. For the rest of the season she was known as the “Accident.”

An attempted mutiny also occurred, when Anderson fired Oluf Pedersen, the beach gang and fishermen’s boss. Anderson appointed Julius Wangford in his place, and managed to calm the situation down, but Wangford was not a good choice, being unable to get along with those he supervised. He finally broke his leg after being thrown down a flight of stairs in a fight and spent the remainder of his stay in Nushagak aboard the Prussia. He was only one of the doctor’s many clients, as there were cases of venereal disease, colds, minor injuries and mental illness to attend to.

The Despatch was finally unloaded and returned to Astoria with mail sent by the crew to their families. The Chinese who had been on board came ashore to their bunkhouse. Fishermen moved into their new boats, put up the boat tents, installed their Swede stoves and slept in the bow of the boats, sheltered by their tents. By this time most of the ice had melted and the tundra was getting soft and mushy. Swarms of mosquitoes came out into the sunshine, a new experience for many of the men. They were paid $1.50 per day for working on the ships on the trip north and for helping unload the vessels and building the cannery, but once the sockeye run began their pay shifted to a per fish basis. At the end of the season their accounts would be balanced, expenses deducted from the total earned, and checks given to them once they were back in Astoria.

Meanwhile the Antelope was on her way north in fair weather at a fast clip. However, she also was not without her problems, which were set down in a letter by the crew to Samuel Elmore.

“We hereby bring your attention to the conduct and actions of the master of said vessel. After leaving the Columbia River bar, and two or three days thereafter, the master was in such condition from the effects of liquor as to not know whether the ship was heading for Alaska or the South Pole and would have continued in such condition if his supply of whiskey had not run out.

Arrived here and this Mr. Anderson, who seems to have charge of the cannery, is carrying things on with a very high hand. Her permitted the vessel to be brought up a slough having a tide rise and fall of 16 to 25 feet without seeing to her moorings or safety resulting in having her rudder post carried away. Rail split and part of her aft rail gone, neither looking after nor drying her sail.

Saturday we worked all day and on Sunday we worked until 1 p.m. When we refused to turn to it being Sunday and informed the mate that we would turn to at 12 midnight if required or any time after, this Mr. Anderson came aboard and ordered us off the vessel, saying that our pay would stop and he would charge us 5 cents for meals as long as our money lasted and then he would put us on the beach which is a serious offence against the U.S. laws so if we don’t arrive with this schooner at Astoria, you know the reason.”

Anderson sent them home aboard the Prussia. Once at home, they sued CRPA for their full wages.

When the sockeye run in Bristol Bay began that summer it was late but large. The CRPA Nushagak cannery was ready for them and worked day and night to pack as much as possible. When the run was over, they had put up the largest pack ever made in a cannery’s first year at Bristol Bay, a total of 25,422 cases. Other packs on the Bay included Alaska Fishermen’s Packing Company with 38,724 cases; Pacific Steam Whaling Association with two canneries packed 75,000 cases; and the three canneries of the Alaska Packer’s Association which packed 174,000 cases. The pack was loaded aboard the Prussia and the Antelope and delivered to Astoria.

Before the Antelope left Nushagak, everything at the new cannery had been sealed up tightly for the coming winter. All of the boats had been brought ashore and secured. Pipes had been drained, windows and doors sealed, and all of the cannery machinery had been oiled and prepared for the long cold winter ahead. They left two winter men there to keep an eye on things until the cannery crews returned to Nushagak in the spring. It was a job that many of the older fishermen coveted. While lonely, the post provided a warm secure place to live with plenty of food, an abundance of leisure, and little hard work. A. Hauke, one of these winter men, sent a letter out to CRPA headquarters on Jan. 13, 1902: “Everything is all right up here. It has been horrible cold the last few days, 50 degrees below zero, but we have plenty of wood and coal so we keep comfortable anyway.”

The arrival of the Bristol Bay fleet at Astoria was a time for rejoicing. There had been no fatalities and no serious accidents. Fishing had been good, resulting in substantial paychecks for fishermen. The first year at Nushagak had been a success for both CRPA and for Samuel Elmore. The pack of 25,422 had exceeded Elmore’s projection of 25,000 cases. A.B. Hammond, however, was not impressed, and queried Elmore in a letter: “Am I to understand from this that your packing in Alaska is over and it amounts to twenty-five thousand cases only?”

Elmore responded detailing management issues with Anderson and with the inside cannery superintendent and mechanic, issues that he dealt with later. The company had invested $88,608.04, and did not make a profit that first year, but Elmore was satisfied with the construction of the plant and its operation. He did admit that they entered the Alaska business at the wrong time, when there were increasing numbers of canneries, resulting in more salmon than the market could take. However, he believed that on the whole the Nushagak plant would become a valuable asset to the company. 17

John Gilbert, a former CRPA employee, put the establishment of the Nushagak plant in perspective in a letter written Jan. 13, 1996.

“To design, outfit, transport and unload all the materials, construct a cannery and successfully operate to process a large pack, all in the same season in Bristol Bay, would be an enormous task even with the modes of transport and technology available in that area today. To accomplish this, as the people of CRPA and other companies did, during the late 1899’s and early 1900’s, was a feat of heroic proportions. I guess they didn’t know any better for it was accomplished stoically, as just part of a day’s work.”

The Nushagak facility was abandoned in 1961. On the stretch of beach known as “Combine Flats” where it once thrived, only a few relics remain.