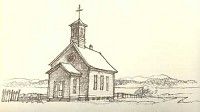

The Oysterville Methodist Church: First Church Building in Pacific County

Published 5:00 pm Tuesday, September 13, 2005

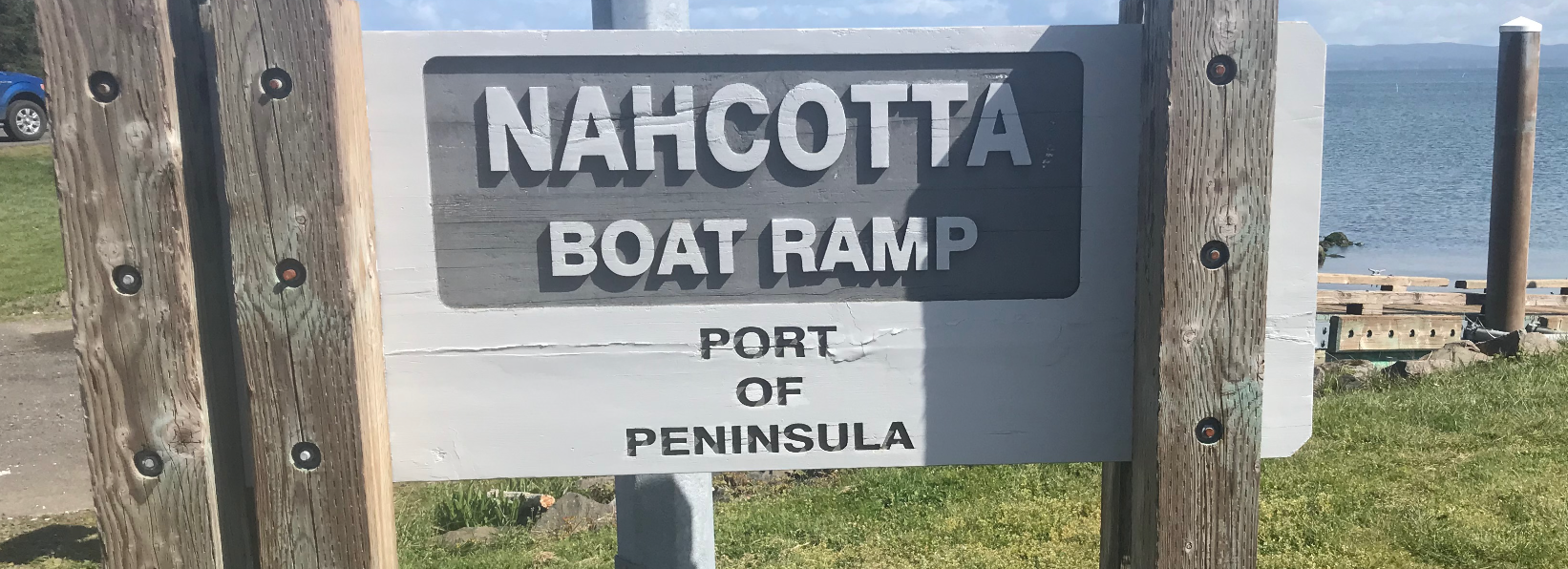

- <I>Earl Thollander drawing, 1977</I><BR>The golden cross atop the belfry in Oysterville was an unusual feature for a Methodist church. It is said that George H. Brown, a Catholic, agreed to give a sizeable donation toward the church's construction in exchange for the minister's promise to top off the building with a cross.

The Oysterville Methodist Church stood at the north end of town for nearly fifty years – from 1872 until 1921. At various times, in addition to its use as a house of worship, it served as a school, a community hall, and as a place of detention or refuge depending upon your point of view. It was the first official church building of any denomination in Pacific County and was built largely through the efforts of two early ministers – Reverend John Devore and Reverend John Dennison.

Devore was a circuit rider who became presiding elder in 1853 of the district that included all of southwestern Washington Territory from his residence in Olympia south to Chinook. Called the John Wesley of the Northwest, his vigorous 36-year ministry spanned the whole era of Washington Territorial history. He was said to have a great sense of humor. When a bishop once joked that Devore was appointed presiding elder, not because he was the best man for the position but because he was the only one available, he replied: “I understand; we had the same problem when we elected you bishop.”

Devore was 6-foot 2-inches tall and was lanky enough to appear frail. Whether or not he purposely misled the mill owner in South Bend regarding his physical prowess is unknown, but the story goes that when it came time to build the Oysterville church, he appeared at the mill on the Willapa River in a “nearly-new frock coat and kid gloves” and struck a deal whereby he could have all the lumber he could load in his sailboat and carry away in a single tide. The industrious Devore immediately removed his coat and gloves and set to work, managing to get back to Oysterville with a cargo that included nearly enough boards needed for the construction of the church!

The main room of the church measured 40×28 feet, with an 18-foot ceiling. At its completion it was described as “a plain substantial building” that cost about $900. Later, a bell tower and a 10×12 foot anteroom with a 12-foot ceiling were added. The bell (now at the Ocean Park United Methodist Church and recently refurbished) was a gift of the John Crellin family. A cross, donated by George H. Brown, was mounted atop the building. Further decoration of the building was provided by a round window of colored glass above the vestibule. The building was located on the northeast corner of Main and Pacific Streets just south of the two-story schoolhouse and across the street one way from Dan Rodway’s Saloon and across the street the other way was the saloon wing of the Pacific House.

According to my uncle Willard Espy in his book “Oysterville, Roads to Grandpa’s Village,” “When the Methodist Church was formally opened, Richard Carruthers, owner of the Pacific Hotel, closed his doors for the duration of the ceremonies, so that his parishioners could pay their respects to the Lord. When the blessings were over, the Methodists and the tosspots alike repaired to the saloon, the Methodists presumably to toast the Father and the Son, while the tosspots, I suppose, toasted the Holy Spirit.

Thereafter, according to Aunt Dora, “Carruthers was always slipping across to the services and getting converted. The townspeople went around saying how nice it was that Carruthers was saved, but then he would black slide again…

“Rodway’s saloon, just across the way from the Pacific Hotel, did not close even briefly out of respect for the new church. But then, Rodway was not one of your come-again-gone-again sinners; he was a sinner all the way through. It is said that no woman ever pushed open his swinging door except to wield a hatchet on the bottles, or to drag home an errant husband.”

Reverend John Dennison was the first circuit rider to be specifically assigned to communities around Shoalwater Bay. He came to the county in 1871, settling in Oysterville, the county seat. Although it was the aforementioned Elder Devore who was known throughout the Territory as “the fighting preacher,” the story goes that it was Dennison who once took issue with a saloonkeeper (perhaps Dan Rodway) who threatened to thrash him. He sent word to the saloon keeper to come on and try. “Tell him I didn’t grow six feet two for nothing.”

The “Methodist Church Record, Oysterville Circuit from 1869 to 1872” lists the following members of the church who were presumably those who supported the construction of the new building: John Sanson Briscoe, Lucy H. Briscoe, Ida G. Briscoe, Burr P. Briscoe, Joseph K. Briscoe, Joe Briscoe, John Briscoe, James L. Campbell, Mary Carruthers, Sophie Carruthers, Lucy Clark, Evelyn Clark, Chas. E. Edwards, Chas. Frazier, Hannah Hanson, Alfred T. Harris, Charles Harrison, Eldridge Higgins, E. G. Higgins, H. Humison, Franklin Humiston, F. A. Jacobs, George Jacobs, Rebecca Jacobs, Julia Jefferson, James Johnson, Jane Jones, Francis Jewett , Merilla H. Johnson, M.J. Luark, John G. Luark, Jennie Luark, Andrew J. McNewel, Anna Parker, A.N. Sayer, Charles D. Soule, Viola O. Stream, Albert Stream, Thomas Warman.

For the half century that it stood, the Methodist church served as a community gathering place. Its main room offered the most commodious space in town and it was there that the school children presented their annual Christmas program. My 93-year-old mother remembers the entire village gathering for the festivities that were the highlight of the year.

Alice Holm, an early twentieth century teacher, described the Christmas program this way: “It was held in the Methodist church down by the bay. The Christmas tree with its uncertain wax candles might well have been considered the first number on the program. For days previously the children devoted his or her handwork to the making of paper chains and Christmas tree ornaments. These they added to the long fairy like strings of white popcorn, and strings of rosy cranberries fresh from the nearby bogs. Bunches of holly from Mr. Stoner’s trees and smell of cedar made one further to know that Christmas had come.

“The audience arrived early, mothers, dads, grandparents, visitors and all others. They came, more or less, laden with babies and the next to the babies, too young for school. They also carried cakes and coffee donated for the social hour.

“The class known as ‘baby sitters’ was as yet unthought of. Mothers shushed intermittently to nip in the bud any wail that might unexpectedly peal forth from their offspring to mar the program or make the mothers themselves conspicuous.

“An air of expectancy pervaded the place. It was a gala event but each sensed the responsibility of doing his bit and doing it well. ‘Hark the Herald Angels sing, Glory to the newborn King!’ The significant air with all joining in filled the room, floated outside to the grassy lowlands and to the bay beyond.”

When the two-story school next door burned to the ground in 1905, the church became the emergency schoolhouse until the new school could be built. My aunt Medora’s friend Asenath Barnes recalled those days in a story written for the Pacific County Historical Society’s 1978 Winter Sou’wester: “We had some exciting times in the new quarters when the winter tides, blown shoreward by high winds, flowed in over the salt meadows and surrounded the church, marooning those of us who didn’t wear rubber boots – until somebody in the village would drag in a flat-bottomed skiff to our rescue.

“There was the day, too, when mothers all over the village became aware, just before supper time, that none of their offspring had come home from school. When one of the fathers was sent to investigate the absences, he found the Briscoe bull, a notoriously cantankerous animal, broken loose from pasture, still belligerently pawing the ground at the foot of the church steps where he had kept the frightened teacher and the rest of us prisoner for the last two hours.”

The Methodist church blew down in a mighty windstorm on January 29, 1921. My mother still talks of watching from an upstairs window of their house as the church swayed back and forth, back and forth, the bell ringing eerily until the building finally collapsed.