World War II: The Airmen of Pacific County County flier survives the infamous Bataan Death March

Published 4:00 pm Tuesday, November 23, 2004

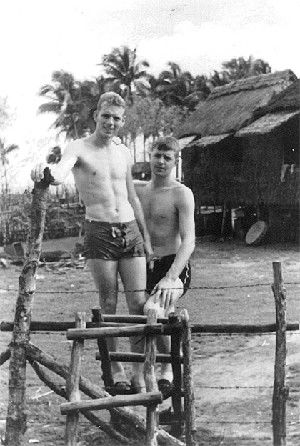

- Buddies heading for a swimming hole: Dick Gillett and Jim Ross (Jim is on the right) in the days just before the Japanese attack. Both survived the Bataan Death March and eventually retired from the Army as lieutenant colonels.

Captain Jim Ross

Raymond17th Pursuit Squadron

U.S. Army Air Corps

Captured at Bataan

in early 1942

Japanese POW

3 1/2 long years

1942-1945

In 1985, husband and wife Jim and Anita Ross walked along the historic and infamous 1942 Bataan Death March route. It was not the first time Jim had walked that road, as he had been there for the inaugural march, the one that had brutally taken 10,000 lives. Jim Ross’ story of World War II is not a tale of military victory; it is a story of the will to survive and heroic personal courage.

Arrival in

The Philippines

Born James Montgomery Ross, in tiny Acequia, Idaho in 1920, Jim grew up in Aberdeen (Idaho) when his father accepted a job with the Kraft Company as a cheesemaker. After graduating from high school in 1937, Ross went on to the University of Idaho, where he was a member of the Reserve Officer Training Corps, or ROTC. He loved to fly and after beginning his third year of college he decided the join the Army Air Corps. In 1940, Ross graduated from class 41-C at Brooks Air Base, San Antonio, Texas.

Within months the new second lieutenant was headed overseas, to the Philippine Islands. While on board the U.S.S. President Pierce, Ross met fellow pilot Dick Gillett, who became a lifelong friend. The ship arrived at Luzon (the Philippines’ main island) in May 1941, but the men’s new base, Nichols Field, was yet to be completed, and their squadron was temporarily located at Camp Iba (Zambales province), an Air Corps gunnery camp in central Luzon.

The squadron’s airplanes were the nearly obsolete P-26s and Seversky P-35As. The P-35As were painted an olive drab, but without a primer coat. When the planes were flown during rain squalls, which were prevalent, the paint quickly peeled away. The 35s looked as though they had been through months of combat before it actually occurred. Dick Gillett recalled the first three months:

When we got there Jim and I were both assigned to the 17th Pursuit Squadron. Then we were sent to Iba, where we stayed for over three months. The living quarters were very cramped, and our cots were next to each other. At lights out we talked and talked. Jim told me about Idaho, and I told him about the desert and the Imperial Valley. We talked until we fell asleep. We flew everyday and when we weren’t flying we were swimming in the ocean. I taught Jim how to body surf, and he taught me how to play poker. After our training was over we returned to Nichols Field in Manila, where we were both checked out in the newly arrived P-40s.

The AirplanesThe Boeing P-26 was the first all-metal pursuit plane produced for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Affectionately called the “Peashooter,” it was the last Air Corps pursuit aircraft accepted with an open cockpit, a fixed undercarriage, and an externally braced wing.

Much faster in level flight than previous fighters, the aircraft’s relatively high landing speed brought the introduction of landing flaps to reduce speed. Boeing designed the P-26, with the U.S. Army Air Corps providing the engines, instruments and other equipment. The first flight took place on March 20, 1932, and the Air Corps purchased a total of 111 of the production version, the P-26A. Many of these planes were used in the Philippines, especially by Filipino pilots.

The Seversky P-35 was a forerunner of the Republic P-47, and was the first single seat, all-metal pursuit plane with retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit. The airplane, first designated as EP-106, went into regular service with the Air Corps when 76 were purchased in 1937-38. The Japanese Navy ordered 20 of a two-seat version of the P-35 in 1938, the only American built planes used by Japan during World War II. Sweden purchased 60 improved single-seat planes, but its second order of 60 were taken over by the U.S. Army in 1940 and designated as P-35As.

The aircraft had one .50 caliber and one .30 caliber mounted machine guns and could carry 320 pounds of bombs. With an 850- pound Pratt and Whitney engine, each P-35 cost $22,000. Most were assigned to the 17th and 20th Pursuit Squadrons in the Philippines, and all were lost in the early action of the war.

In 1937, the U.S. government had asked for a new fighter plane, one that could challenge the Germans and Japanese. Within a brief time Curtiss came up with the P-40, with Lockheed and Bell designing what became the P-38 and P-39. Wanting a tried and tested design, the Army first chose the P-40. The plane quickly went into production, and in 1940 was sent to several American air bases. Understanding the aircraft’s strengths and weaknesses allowed pilots to perform to expectations. Positive attributes included good armor, firepower, roll rate and dive speed. Its shortcomings included an inability to outmaneuver the Japanese Zero, an interior turn rate, and a slow rate to climb. To compensate, pilots were taught to use the airplane’s superior diving speed to hit and run.

With its distinctive shark’s mouth painted on its nose, the P-40 was one of the most recognizable fighters of World War II. The aircraft’s fame came about with the legendary Flying Tigers, a group of American mercenaries who volunteered to defend China against the Japanese. Although many critics thought the P-40 was slow and obsolete (not really true), its importance in the Pacific theatre of war was unquestionable.

War Comes To The PhilippinesAn American GI at Nichols Field wrote to a friend in early November 1941. With the knowledge of what was to happen in less than a month, we readers can wonder about the crewman’s fast fleeting innocence and security. The letter begins with the notation, “17th Pursuit Squadron, Nov. 10, 1941.”

Dear Buck,

Received your letter today and was very glad to hear from you. I knew the Yanks would beat the Bums (Brooklyn Dodgers) in the World Series; by the way, just how far did Boston finish behind the Yanks (ha!)? I heard about the accident that Mr. Dempsey got into. Well, I guess that it was just one of them tough breaks. I’m having a pretty good time myself over here. Manila is only about six miles from the camp and you can have some neat times down here. Down in Rizal Stadium is the ball park. Inside the stadium they have the names of people who have hit home runs in that park painted on the walls. You remember when the Major League All-Stars went over to Japan to play ball? Well, they stopped here to play, and Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bill Dickey, Jimmy Foxx, Earl Averill, and Charley Gehringer all hit home runs in one day. The park over here puts me in mind of (Brooklyn) Dodger Stadium, only it is not quite as good. I am working quite hard as of this writing, but I hope this war scare gets over soon. We are getting new P-40s to replace the old P-35 airplanes and it is hard since I have to take care of all of the .50 caliber machine guns that go on each plane. I’m the armorer, and the work we do is to take care of and fix broken guns of all sorts. By the way, what are you doing with yourself besides picking potatoes? You have never seen any of the world until you have been over here. Over here are all of the races of the world. It seems funny being so far away from home and not being able to get back. I never thought that and when I enlisted thought I would ever come over here. Well, I guess I’m out of words, so goodbye.

Your pal, Doug Larlee

One month later, Japanese forces attacked the Philippines. The initial attack came on the morning of Dec. 8, 1941, which was the same day of the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Because of the International Date Line, the dates are different: Dec. 7 in Hawaii, and Dec. 8 in the Philippines.)

P-40 Warhawks had arrived in September, but many of the P-35As had to be flown in combat against the Japanese invaders in December and January. Unfortunately, P-35s were not the match of the Zeros, but the pilots bravely flew them anyway, and at times with some effect. In fact, Dick Gillett was the lone P-35 pilot to shoot down a Zero.

The American command had always believed that the Japanese would hit the Philippines first, but they were sadly proven wrong. It was the surprise attack on the Hawaiian Islands that had them stunned. Ross and his comrades immediately went to their flight line and helped in getting the senior pilots off to an auxillary field. For everyone, there was nothing they could do except to try and stay calm. They wrote letters home, but they were never delivered. Clark Field was bombed, and after sundown the men at Nichols Field heard airplane engines that were not theirs.

Within 30 minutes of hearing about Pearl Harbor, radar at Camp Iba airfield plotted a formation of unfriendly airplanes 75 miles offshore, heading for Corregidor Island. A squadron of P-40s was sent up, but failed to make contact. Shortly thereafter, B-17s at Clark Field were ordered into the air to evade a Japanese attack. The enemy fighters swung east to bomb military installations at Baguio, Tarlac, Tuguegarao, while the airfield at Cabantuan was also attacked. Within an hour of noon the B-17s that earlier had been sent into the air landed at Clark and Iba for refueling.

Radar disclosed that another flight of Japanese aircraft was headed south, possibly toward the Bataan Peninsula. Just before noon the Japanese hit Clark, where American bombers and fighters were destroyed on the ground. It was at this time that Sgt. Stan Domin, of Willapa, was killed. At Nichols Field it was much the same. Dick Gillett later told of the fear he, Ross, and the others felt.

The air raid alarm sounded and the pilots and crewmen had no foxholes, just concrete to lie flat on. We found ourselves trying to burrow in with our bare hands. The raid last just five minutes, but everything was on fire, especially at the base gasoline dump … We started running, not knowing where to go, and heard a call for help. Two airmen were on the ground. Jim picked up the bigger one and placed him over his shoulder and started moving away from the fire. I had trouble getting my man up, then I realized that his right arm was missing. I followed Jim, my legs so weak that I could hardly walk. We made about 50 yards and an ambulance arrived. Jim put his man in the ambulance and walked back to help me out … Medical corpsmen then took over. We thought we were still being bombed as the 50-gallon gas storage tanks were still exploding…

Soldiers at nearby Fort McKinley could see the explosions. Ross and Gillett got back to their living quarters to discover they were covered in blood.

All the pilots experienced hellish problems. Confused American ex-cavalrymen of the New Mexico National Guard, manning anti-aircraft guns, shot down three P-40s, thinking they were Japanese Zeros. Although the inexperienced gunners were confused by the P-40s, the P-35s resembled the Zeros even more.

When embattled pilots were ordered to fly their airplanes to Bataan Field in January 1942, nervous gunners shot them down as they tried to land. Gillett was fired upon, and with oil splattered across his windshield, he noticed his oil pressure had fallen to zero. He opened his cockpit, inverted to bail out, but then luckily saw the airfield in front of him. He rolled upright, and brought the craft in, dead stick (without engine or power).

When Gillett was told he would have to wait ten days for repairs, he suddenly became an infantryman.

Bataan PeninsulaLuzon’s Bataan Peninsula is approximately 60 miles from the tip to the end, and is shaped like a jar. The Japanese were at the top, pushing the retreating American and Filipino troops further and further down the peninsula. Forced to do with what food they had, and without boats and air cover, the men were trapped; they were without an escape route.

On Christmas Eve, 1941, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered all military personnel to evacuate to the Bataan Peninsula.

The trapped Americans faced a jungle that was as thick and as difficult as any in the world. There was no sanitation, not enough food, with the enemy controlling the air and sea. They flew over American and Filipino outposts whenever they chose, leaving them with no place to go. Starving Americans shot their cavalry horses and ate them. They also ate monkeys, and were forced to live in their own filth.

The 17th Pursuit Squadron had partly gone to Bataan by boat during one night’s excursion. The squadron was ordered to the west coast of the peninsula to engage the Japanese coming down in barges from behind the front lines. The jungle there was cold and damp, and the squadron was relegated to use World War I rifles against an enemy that had automatic weapons.

Ross and Gillett both had knowledge of guns and gave instructions to airmen who had never fired a rifle. There were many casualties, but they stopped the Japanese from advancing. After two months the big guns at Corregidor dropped many artillery shells in the area where the Japanese were camped, and it is estimated that over 3,000 of them were killed. The fatigued 17th suffered from some friendly fire casualties, then were ordered to go to the end of the Bataan Peninsula for some much needed rest.

Ross and Gillett heard that their commanding officer had been killed in the jungle, then came word that Bataan had surrendered. They had no communication with anyone, and the Japanese continued to bomb everyday. Gillett remembered how Ross helped those around him.

Everyone was asking questions, like ‘What are we going to do now? How are we going to eat? What’s going to happen to us?’ Jim told them to settle down, that we needed to stay together. Jim and I had had thoughts of escaping in a boat we knew about, but we were the only officers there and he said it was our duty to stay with the enlisted men, and I agreed. That sums up the kind of man Jim Ross was. Always doing what was right.

Some GIs from other units were coming through our camp looking for a way to Corregidor. They told us that we were supposed to go to Kilometer Post 181 and wait for further instructions. We waited there until the bombing stopped. Jim told everyone to dispose of all guns and ammunition, and then we walked down to the road that was several miles away.

Gen. MacArthur had gone, escaping to Australia in March 1942, leaving tens of thousands of his troops behind. At Bataan, after General King surrendered to the Japanese, the enemy turned their guns against the small island of Corregidor. Then, for an inexplicable reason, the starving American and Filipino prisoners were force-marched off the Peninsula.

The Death MarchThe Americans and Filipinos, having already suffered greatly from a lack of food and medicine, suffered even more from the 65-mile forced march.

The men were moved too quickly, with little water in the tropical weather. If a man fell by the wayside, he was likely killed. The captors did not slow the pace or provide their prisoners with trucks, nor did they feed them or give them water. It is known as one of the great atrocities of World War II.

Of the 62,000 men who began the march, nearly 10,000 died. Most of the dead were Filipinos, but many hundreds were Americans. Dick Gillett later recalled the time of the American surrender, and the Death March.

Just before our capture we had gotten to a road where several hundred men and officers had already gathered. Nobody knew what to do or expect. Jim and I were exhausted, and found some trees off the road, and we laid down and went to sleep.

When we woke up it was morning and Japanese soldiers and tanks surrounded the area. They told us to march down the road toward Mariveles. There were thousands of Japanese troops there and they took everything we had. With the confusion I lost track of Jim. Thousands of Japanese troops were arriving for an assault on Corregidor as the guards tried to march us out. There was no food or water. The next night I found Jim inside the barbed wire confinements they held us in. For the next six days it was more of the same.

This was the Death March, and it was ten times worse than anything you have ever heard. We had been without food since before the surrender. Exhaustion does not describe what we endured. There are no words to aptly describe how thirsty we were, how hot the tropical sun was, or how sadistic some of the Japanese guards were. But I can say the bond Jim and I had was something special. The times I needed him he was there, and I for him. It is difficult for me to describe this bond, but it was a closeness that lasted our entire lives.

After six long days of marching, the men arrived at a railroad heading where the Japanese ordered them into small boxcars. The men, all in a standing position, were pushed together before their captors jammed in even more prisoners. When the train began moving there was some relief as air circulated through the open doors. The train went only 30 miles before the men were again on the march. Gillett, who had a high fever, recalls that many of their comrades lay dying.

Jim had to hold me up and practically carry me as I could hardly walk. We finally made it to a run-down Filipino army camp, Camp O’Donnell. I survived because of Jim. He brought me water several times a day. Later, a doctor looked at me and told me I had dengue fever, which is worse than malaria. Three months later I was transferred to a better camp, and met up with Jim, who had been taken from O’Donnell to work in a Japanese labor camp. This camp was in Cabanatuan, and we were held here for about three months.

Forced Labor in JapanIn December 1942, the Japanese captors chose about 1,000 comparatively healthy POWs, put them in box cars, took them to Manila, and ordered them aboard freighters bound for Japan.

Several days later the ship was attacked by an American submarine, but miracously evaded being sunk. The men also survived a typhoon. Stories of these close calls were not unusual at this time. One former POW, Kenneth Calvit (in a separate prison camp), wrote of a similar experience: “On Aug. 17, 1944, I shipped out from the Philippines to Japan aboard the Noto Maru. American subs attacked the convoy off Formosa but missed us and got a large oil tanker. That lit up the sky. We arrived in Hanawa on Sept. 6, and worked as slave laborers in a copper mine for Mitsubishi the last year of the war.”

At sea for New Year’s Day, 1943, Ross and Gillett had no idea where they were being sent, but were grateful to still be together. After 29 days at sea the ship landed in Japan, where the men were taken to a slave labor camp in Osaka. Ross was assigned to a blast furnance area, while Gillett worked in a machine shop. The weather turned very cold, and the prisoners had few blankets and clothing to keep them warm. Within three months, 105 POWs had died, but Ross and Gillett were among the lucky survivors. Gillett recalls those terrible times.

Everybody slept together to keep warm, so Jim and I kept each other from freezing at night. The Japanese civilians that we worked with treated us well, but some of the military could be brutal and evil. They were the main reason for so many unnecessary deaths. Our food was a small bowl of rice, hot water with seaweed, or some other vegetable that was hardly edible. They gave us tea three times a day.

After about a year and a half, 25 of us were transferred to a camp called Zentsuji, on the island of Shikoku. As luck would have it, Jim and I stayed together again. This camp was where our military from Guam had first been taken. They had been allowed to take a footlocker and a handbag when they were sent to Japan, and a cruise ship had brought them there. The prisoners were all U.S. Naval officers, and they complained that because of us they would be forced to sleep three to a cabin. Here we were in dirty work clothes and we had ruined their luxury cruise.

Shikoku was easier, and we now had plenty of blankets, and we worked only a half day. The work was easy gardening, and most of us volunteered to work the other half day because there was nothing else to do. Some of our POWs were chronic complainers, and became bitter to the point they lost their will to live. On the other hand, the rest of us kept each other’s spirits up, and made the best of a bad situation. We talked about what we would do when we got home, not if we got home. We truly learned that attitude is everything.

LiberationToward the end of the war the POWs were again transferred, this time to the west coast of Honshu. They became stump removers, preparing new farm land for rice paddies. The camp was very high up in the mountains, as the Japanese had been forced to develop unused land for increased rice production.

On one day in August 1945, the sky appeared very smoggy, very ominous looking. The next thing we knew was that the Americans were using an ‘illegal’ weapon. In mid-August the camp commander had our entire camp in formation. He told us the U.S. and Empire of Japan had quit fighting, but we would remain POWs until a formal treaty was signed. About three weeks later, on Sept. 2, we had another camp formation. The commander told us the treaty had been signed, and that we were no longer POWs. Instead, we were now ‘guests’ of the Emperor.

Soon supplies were being dropped by B-29s, all sorts of food, clothes, shoes, and soap. The food included Spam, peaches, fruit cocktail, and other things. The next day we were sick from all our gorging. Finally we were moved to Yokohama where we boarded a transport ship.

Detoured to the Philippines, the men stayed there a week before taking the last leg of their trip home to the Port of Seattle and Madigan General Hospital in Tacoma. After medical exams, Ross and Gillett were finally allowed to go home, for a 120-day leave. It had been nearly three and a half years since their capture at Bataan.

EpilogueBoth Dick Gillett and Jim Ross stayed in the military, and both retired in 1966 at the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Ross spent 26 years in the military, at SAC bases in England and Guam, and domestic bases in New Hampshire, Florida, and California. During his career he earned a civil engineering degree and MBA from the Air Force Institute of Technology. Upon retirement from the USAF, Ross took a job as an engineer for the Washington State Department of Transportation. First at Chehalis, the job took him and Anita and their family to Raymond in 1974.

Sources and Notes1. Interview with Anita Ross, July 2004. Jim was strictly a smalltown boy. His birthplace, Acequia, Idaho, presently has a population of 144, in a very dry area that does not exceed 0.3 square miles. Acequia is 8 miles north of Rupert (Minidoka County) and just south of the former World War II Japanese-American detention center (also known as Minidoka). Aberdeen, Idaho (pop. 1,600) is situated along the American Falls Resevoir, and across this body of water from the city of Pocatello. Anita is from San Antonio, Texas. While stationed in Texas after the war, Jim and Anita met on a blind date. Coincidentally, Anita’s uncle, Col. Stanton T. Smith, was the CO of Brooks AAF Base when Jim earned his wings in 1940. Col. Smith later served with General Spaatz in the European Theatre of War (ETO).

2. Jim is buried at the Tahoma National Cemetery.

3. “Jim Ross: A Reluctant Hero,” a eulogy written by Dave Gauger, 10 March 2003.

4. Jim Ross eulogy, written by Shawn Dunsmoor, 10 March 2004.

5. “Big Jim” Ross,” a history/eulogy written by Richard Gillett.

6. Airplane information: (a) “The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk,” Patrick Masell. (b) “Boeing P-26,” USAF Museum: Early Years Gallery. (c) “Seversky P-35A,” USAF Museum: Early Years Gallery. Internet access.

7. “Kenneth Calvit’s Biographical Sketch,” Internet access.

8. “From Nichols Field in Rizal,” a letter from Douglas Larlee. Internet access.

9. “Better To Be Lucky Than Good,” by Thomas McKelvey Cleaver, Flight Journal, August 2003, Vol. 8, No. 4. A story about Richard Gillett.

10. Philippines’ 1980 population figures: Bataan provice, capital is Balanga, pop. 323,250. Zamabales province capital is Iba, pop. 440,000.

11. Jim Ross’ parents were Frank and Cora Montgomery Ross. He had three brothers and one sister: Frank, Jr. (a German POW during WWII), Gerald, and Carroll. His sister is Shirley Ryan.

12. Jim and Anita Ross have three children: (a) James, Jr., born 1949., and graduated from UW. He lives near Bellingham; (b) Virginia, born 1950, lives in Australia, and has two sons; (c) Cindi Dunsmoor, born 1965, is a graduate of the UW and lives in Oroville. She and her former husband have two children, a son and a daughter.

13. Sgt. Stanley Domin, Willapa. As mentioned in the text, Stan Domin was killed at Clark Field. A B-17 gunner, Stan had enlisted in the Army Air Corps on Nov. 19, 1939, and had been trained as an airplane mechanic at Rantoule, Ill.; March Field, Calif.; and Alburquerque, N.M. On Oct. 13, 1941, Sgt. Domin’s B-17 squadron was given orders to fly from Albquerque to Clark Field in the Philippines. Specific information about Sgt. Domin’s death is a little vague, but it is believed that he was in his barracks when the Japanese attacked Clark Field on Dec. 8. Stan Domin had been born in East Raymond on Sept. 10, 1918, and had graduated from Valley High School in 1937. He was a reserve on Valley’s 1936 state basketball championship team.