Speakers illuminate lives of Clark, his slave York

Published 4:00 pm Tuesday, February 25, 2003

- Speakers illuminate lives of Clark, his slave York

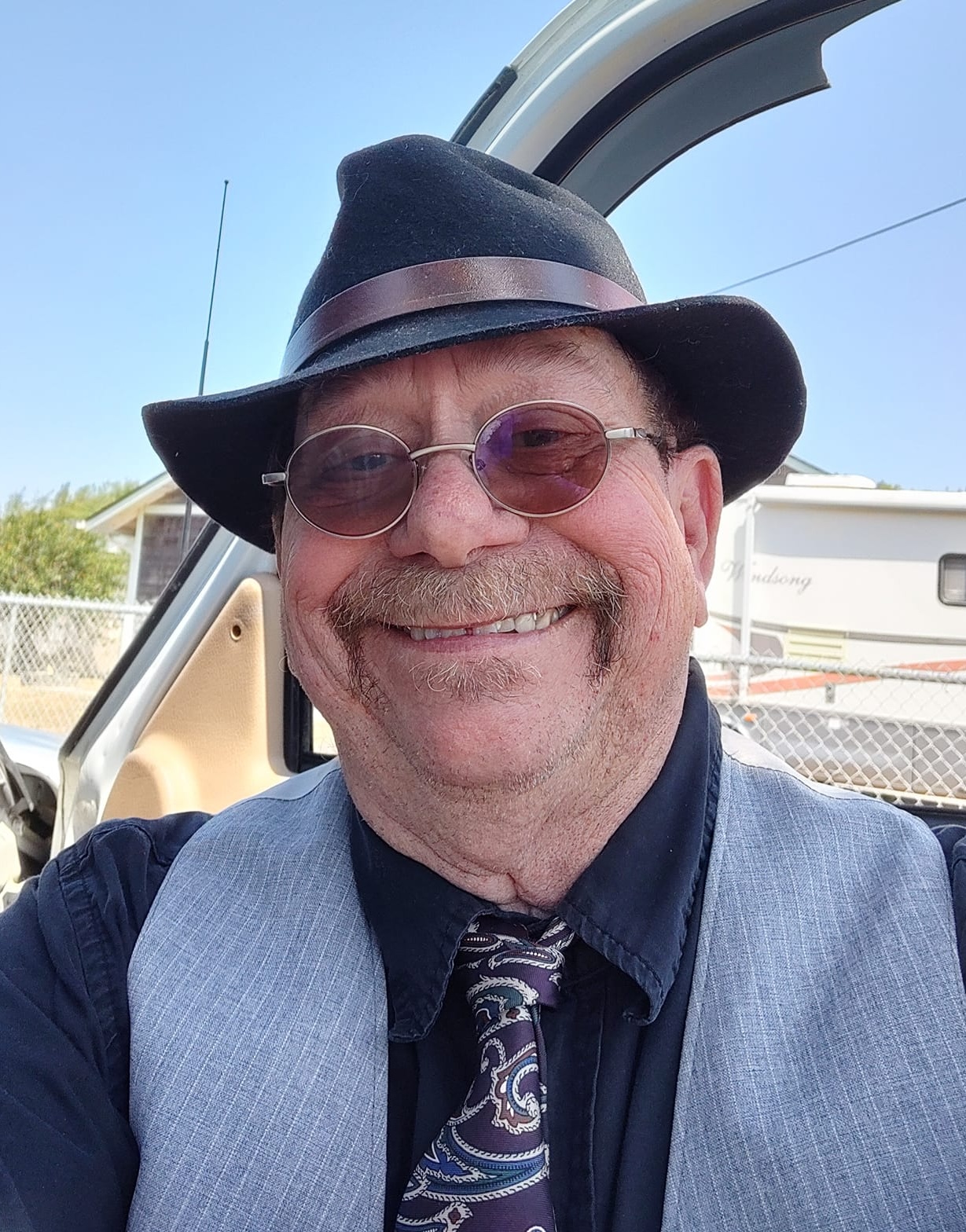

ILWACO — A standing-room only crowd came to the Inn at Ilwaco Saturday afternoon to hear filmmaker and author Ron Craig and historian James Holmberg discuss little-known aspects of two members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition – William Clark and Clark’s slave, York.

Craig, who owns Filmworks Northwest in Portland, is co-author of a children’s book about York, the only African-American member of the expedition, to be published by National Geographic in 2005 to coincide with the Oregon and Washington Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Signature Event in 2005. He’s also working on a documentary about York.

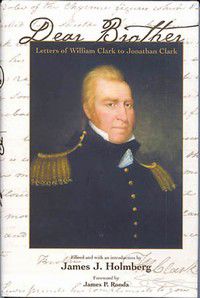

Holmberg is curator of special collections at the Filson Historical Society in Louisville, Ky., and the author of “Dear Brother,” a collection of letters from William Clark to his brother, Jonathan.

“About four years ago, I started getting personal about York,” Craig said. “I’m a native Oregonian and was a Boy Scout. We really related to the expedition. We grew up on those guys. But I never knew there was an African-American member of the expedition. When I found out he was Clark’s slave, it didn’t sit right with me.” He talked to his nieces and nephews and they didn’t know about York either. That’s when he decided to start work on the documentary film. “You can change history,” he said, “the stories of African-Americans, women, indigenous people. They need to be honored.”

York was more than Clark’s slave, he said. “There are things we can do so people really know about him.” For example, the Portland City Council recently voted to dedicate N.W. York Street in Northwest Portland to the expedition member. Coincidentally, the street is two blocks from the site of the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial location.

The goal of his children’s book, Craig said, is to give kids at the fifth-grade level “a look into York’s history.” He added that he has a “dream team” of scholars working with him to be sure the book is “exactly true to what York’s life was about.”

One of those scholars is Holmberg. The two have been friends for several years. “We have the same passion to tell the story of Lewis and Clark and York,” Craig said. “When I saw the actual handwriting of Clark in his letters to his brother, I didn’t know how emotional I would get.”

Holmberg said his goal in writing “Dear Brother” was to bring the expedition, “an American epic, and the greatest exploratory adventure in the history of the United States, to everybody. How much poorer we would be if he hadn’t written those letters from unexplored country,” he said. “They literally were stepping into the unknown.” Both authors said their research has shown that people today aren’t so different from people of 200 years ago.

Holmberg’s story of finding the letters was an epic in itself. Their existence was unknown until 1988 when some of Clark’s descendants were clearing out the family home in Louisville. In the attic were two trunks filled with letters that nobody had seen in years, including those of William Clark. Besides Clark’s letters to his brother were letters from family members dating to the American Revolution.

When the family realized what was in the trunks, they put them in a safe deposit box. A local historian called Holmberg, asking if he had heard of the treasure trove of history. “I literally clutched my chest and said ‘No. Tell me more.'”

Some of the letters, he said, were written at the mouth of the Missouri River and Fort Mandan. “On my birthday, I saw them for the first time. Talk about a rush! I was shaking with excitement.” Among the letters were five from Clark while he was on the expedition, before they began the famed journals. “They filled in gaps and contradictions of the known record,” he said.

Some historic documents weren’t so fortunate. He heard about a couple cleaning out Clark’s home in the 1930s. “Trunks and trunks full of papers were thrown out the second-story window,” he said.

Jonathan Clark was 20 years older than William and had been his best friend and a father figure. “He wanted to stay connected with him on the expedition and to benefit from his advice,” Holmberg said. “Jonathan had the reputation of being one of the wisest men in the country at the time. He should have written an advice column.” No letters from Jonathan survive.

The letters span 19 years until Jonathan’s death in 1811. “I will write without reserve,” Clark, who was known for his creative spelling, says. “You must not expect connections, grammar or spelling in my letters.” Clark reports in one letter that his wife, Julia, is in the room, looking over his shoulder as he writes and comments on his spelling. “Don’t let the children use your letters for spelling lessons,” she says to him.

“These letters are on a more personal level than any other information about Clark,” Holmberg said. He noted on one occasion that people were pouring into St. Louis, bringing picnic lunches, to view a public hanging.

His marriage to 16-year-old Julia in 1808 “makes me look about and accumulate a little for a future day,” Clark says before the birth of his first son, Meriwether Lewis Clark. He reported giving the new baby a bath. “He is very fond of being washed in whiskey after his bath,” he says.

Holmberg said many myths surround York and Lewis. “It’s been said that Clark freed his loyal slave and set him up in business but he died of cholera. There’s a lot more to it than that,” he said. “The letters show the story exactly. Clark was a product of the time and came from a slave-holding society and family. York was in an inferior position his whole life and believed he should have special consideration. But York’s wife is owned by someone in Louisville. Clark thinks he should forget her and make a new life. It sounds callous but that was the society of the time. He threatened to send York to New Orleans and sell him to a severe master, the worst fate a slave could face.” Clark never followed through on the threat, though, and 10 years after returning from the expedition, York is still Clark’s slave and he beats him for being insolent.

Myths of Lewis’s death persist, Holmberg said. Was it murder or suicide? “He cartwheeled downhill after the expedition returned. In some ways he never readjusted. No woman would marry him, he was financially overextended, accused of malfeasance by his political enemies, drank too much, had malaria, took laudanum and, three years after the expedition returned, he hadn’t written a word of a history of the trip he had been under contract to write. He was probably manic-depressive.”

Holmberg said Clark read about Lewis’s suicide in a newspaper and writes to Jonathan “I fear the weight of his mind has overcome him.”

After Holmberg’s book was published, he says the perfect quote for the front of the book came to him. From Pliny the Elder, he said the quote captured William Clark the man – “True glory consists in doing what deserves to be written and writing what deserves to be read.”